This article was prepared jointly by CAMERA and UK Lawyers for Israel. Their joint press release can be found here. Their extended reply to the Harvard clinic’s submission can be found here.

On 28 February 2022, the Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic jointly submitted a report, alongside the organization Addameer, to a United Nations commission of inquiry against Israel, accusing the Jewish state of committing “apartheid.”

Unfortunately for Harvard’s reputation, that is not what the submission ends up showing. Instead, the submission shows that the students involved have failed to comprehend basic concepts of the rule of law. From committing basic legal analytical errors that would get them laughed out of court to getting basic facts wrong, here are just seven of the errors made in the submission.

1) Are Jews “Privileged” or Not? The Harvard Law Clinic Can’t Decide.

The submission repeatedly states that “rights and protections” are given to “Jewish Israelis,” implying the rights and protections are afforded only to Jews. This claim forms the basis of the report’s entire claim of “apartheid.” However, the submission itself admits the intellectual dishonesty of the statement by admitting those “rights and protections” are “guaranteed to citizens” (emphasis added), which includes Israeli Jews, Muslims, Christians, Arabs, Druze, Circassians, et cetera.

Distinctions based on citizenship are not just common sense. They are expressly allowed for under international law. Moreover, making Palestinians citizens of Israel would amount to the repudiation of the two-state solution.

The report attacks Israel for applying Israeli domestic law, and not Israeli military orders, to “Jewish Israeli settlers.” The statement is deceptive and, importantly, omits the application of Palestinian self-rule.

First, military law can be applied to Israeli citizens. Some of the same measures complained about by the submission are also applied against Israelis. Just a couple months ago, a Jewish Israeli man was put under administrative detention out of concern for “the security of the country and the public” after allegedly vandalizing Palestinian vehicles and assaulting activists.

Second, certain domestic Israeli laws do apply to “Jewish Israeli settlers,” but they also apply to all other Israelis, regardless of religion, national identity, or ethnicity.

Third, the submission ignores the existence of another justice system. Under the Oslo Accords, the vast majority of Palestinians, who reside in Areas A and B – where Jews are prohibited from residing – are subject to the Palestinian Authority’s justice system.

In other words, in Judea and Samaria, Israeli citizens are subject to some Israeli domestic law while Palestinians are subject to Palestinian Authority law. In Area C, where both Israelis and Palestinians reside, both groups are subject to Israeli military law (which, assuming the territories are “occupied,” is the applicable legal regime anyway).

In order to find a situation of “apartheid,” one must examine the intent behind various laws and policies in a given situation. So when the authors accuse Israel of committing “apartheid” by pointing to a variety of security measures enacted by Israel, one would think they would have engaged in an analysis debunking Israel’s proffered security justifications.

Instead, the submission simply proclaims:

“Notwithstanding Israel’s legitimate security interests, the scale and sweeping nature of the ongoing suppression of Palestinian rights fails any justifiable balancing test between the protection of human rights and underlying security needs.”

Nowhere does the submission actually engage in a balancing test. Instead, it simply states as fact that Israel’s measures fail this unexplained test. Surely, as law students and professors, the authors understand that if they were to tell a judge that their opponent fails a relevant judicial test without explaining how or why, they would be deservedly laughed out of court.

The submission claims that “Israeli actions and policies…manifests an intent to establish and maintain Jewish Israeli domination and suppression of Palestinians.” Nowhere does it grapple with the fact that in the 1990s, Israel agreed to the Oslo Accords, granting Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza substantial autonomy they had never held before in history.

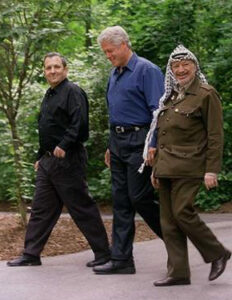

Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, U.S. President Bill Clinton, and PLO head Yasser Arafat during peace negotiations in 2000.

Then, in the much-lauded negotiations at Camp David in 2000, Israel agreed to giving the Palestinians their own state in almost all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, with minor land swaps, only for the deal to be rejected at the last minute by the Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

Half a decade later, Israel would unilaterally disengage from the Gaza Strip. A few years after that, the Palestinians, under Mahmoud Abbas, would reject even more generous offers than at Camp David, including one that would have given the Palestinians 93.7% of the West Bank, Israeli territory to make up 5.8% of the remainder, and a corridor between Gaza and the West Bank to account for the remaining 0.5%.

This consistent Israeli behavior, of making and offering painful concessions in order to achieve peace and grant Palestinians their own state, is fundamentally incompatible with the allegation that Israel intends to “maintain Jewish Israeli domination and suppression of Palestinians.” Yet nowhere is this addressed by the authors.

The authors claim that figures from the organization Yesh Din show “1,293 reported settler violence cases between 2009-2019.”

That figure is inaccurate for two big reasons. First, the Yesh Din figures are for 2005 to 2019, adding an additional four years during which these alleged cases occurred. Second, those 1,293 cases are not all “settler violence” cases, even assuming the accuracy of the figures from Yesh Din, an organization known to be highly critical of Israel. According to Yesh Din, only 36% of those cases, or around 465, were “violent offenses.” That’s approximately 31 violent attacks per year by “Israeli Jewish settlers.”

The aftermath of a stone throwing attack near the Israeli town of Huwara in the West Bank. A father and his two children, ages two and four, were injured in the attack.

The authors’ allegations also look entirely absurd when put into context. According to data from the Israel Defense Forces, by mid-December 2021, there had already been 6,633 attacks against Israelis in Judea and Samaria that year alone, including 61 shootings, 18 stabbings, 1,022 fire bombings, and 5,532 stone throwing attacks.

Using the data from these two sources, there are approximately 214 times more violent attacks by Palestinians than by Israelis in the West Bank. Yet, Harvard Law students decided to portray the “Israeli Jewish settler” attacks as the ones that have been allowed to go on uncontrollably.

The Submission cites, as an example of inhumane acts, “Israel’s harassment, arrest, and detention of Palestinian Legislative Council members—eight of whom were currently detained as of February 2022,” with the implication that Israel is somehow preventing Palestinians from participation in political life.

Some background: the Palestinian Legislative Council (“PLC”) last held an election in 2006, when the terrorist organization Hamas won a majority of the seats (74 of 132). It has not met in regular session since 2007 when Hamas violently took control of the Gaza Strip from the Palestinian Authority. In short, the PLC “has ceased to function.” It’s hard to “prevent political life” when the legislative body at issue has shown no signs of life to begin with.

The report does not specify who are the eight imprisoned PLC members. We can presume that among them is Marwan Barghouti, a senior terrorist who is serving five life sentences for his role in the murder five Israelis in three terrorist attacks. Another would be Ahmad Sa’adat, the Secretary-General of the U.S.-designated terrorist organization PFLP. There is also the cofounder of Hamas, the rabidly antisemitic terrorist organization which celebrates when it murders Holocaust survivors, Hassan Yousef. Other recently detained PLC members listed by the submission’s coauthor, Addameer, are Hamas officials, many of whom are designated by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control for their terrorist activities.

While trying to attack Israel over the topic of administrative detention, the Harvard Law students only succeed in demonstrating a disturbing failure to understand the fundamental importance of applying the correct legal standards.

Administrative detention is a lawful security mechanism under the Geneva Conventions for the inevitably complex security environments of “occupied” territories. It is very different from criminal law procedures. Under international law, as explained by Dinstein, administrative detention is a “measure of preventive rather than punitive nature.” While criminal procedures govern trials for those accused of having committed crimes, administrative detention deals with prospective threats. Such detention is permitted for “imperative reasons of security,” according to the Geneva Conventions, including “the overall security of the civilian population in the occupied territories,” as the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom explained.

The rules surrounding the use of administrative detention are thus very different from those governing criminal trials, including those conducted by military courts. Yet, the authors of the submission appear not to understand these basic differences, attacking Israel’s application of administrative detention by comparing it to Israeli civilian courts.

For example, criminal procedure rules such as the period of time a suspect may be held without indictment are entirely irrelevant to an analysis on the lawfulness of an administrative detention. When the authors tried to apply the former to the latter in their report, they either didn’t actually understand what administrative detention is, or they were deliberately trying to mislead readers.

Neither scenario reflects well upon Harvard Law.