As readers may recall, since late last year various BBC radio programmes have misled their audiences by promoting assorted versions of the inaccurate claim that Dorit Rabinyan’s book ‘Gader Haya’ (‘Borderlife’) has been banned in Israel.

December 2015, BBC World Service: BBC World Service ‘Newshour’ reports a ‘book ban’ that does not exist.

January 2016, BBC World Service: BBC World Service continues to promote the fiction of an Israeli ‘book ban’.

February 2016, BBC Radio 4: How an uncorrected inaccuracy became BBC conventional wisdom.

March 2016, BBC World Service: BBC WS yet again promotes inaccurate claim of Israeli book ‘ban’.

With previous efforts to alert BBC World Service programme makers to the inaccuracy having proved fruitless, after the February 22nd broadcast of ‘Front Row’ on Radio 4, BBC Watch submitted a complaint concerning the following inaccurate claims made in that programme:

“…recently the [Israeli] culture minister banned a novel about a mixed Israeli-Palestinian relationship…ahm…Dorit Rabinyan’s ‘Border Life’.”

As readers may recall, the complaint was twice rejected by the BBC Complaints department, with the second response including the programme production team’s claim that:

“This was a discussion that wasn’t specifically about the Rabinyan case – it was about another author’s work and the discussion strayed into political interference in Israeli culture. As such, Samira used the shorthand “banned” in reference to the book. The book was removed from the school syllabus, but in a discussion as wide ranging as this, the point about political involvement in arts and culture still stands whether the book has been banned from society at large, or removed from the school syllabus. The decision to interfere in the distribution of this book was made by, or under pressure from, politicians. That was the point the interviewee was making and to which the presenter responded.” [emphasis added]

As we noted at the time:

“The book ‘Borderlife’ was not “banned” in Israel and is freely available to all would-be purchasers in book shops. Neither was it “removed from the school syllabus” – because it was never on it. The decision not to include the book in the curriculum was made by a professional pedagogic body – not “by, or under pressure from, politicians”.”

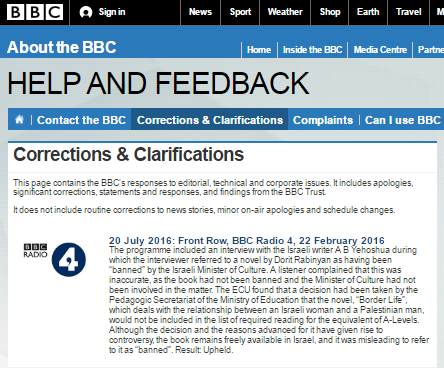

BBC Watch pursued the matter further and the BBC’s Editorial Complaints Unit upheld our complaint, as is now noted on the BBC website’s ‘corrections and clarifications’ page.

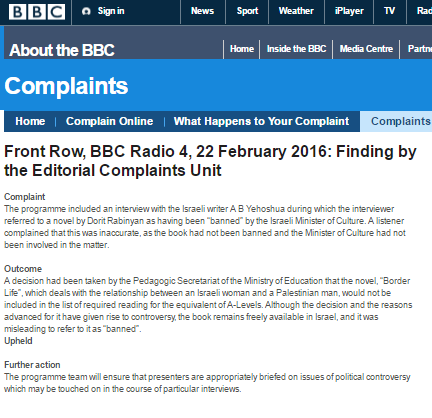

The ECU’s reporting of its findings includes a section titled ‘Further action’.

During our correspondence with the ECU, we raised the question of how the listeners who were misled by the inaccurate broadcast would be made aware of that fact and suggested that an on-air correction in the same programme would be the most efficient way of ensuring that a correction reached the original audience.

We learned from the ECU that the practical steps to be taken after a complaint has been upheld are left to the discretion of the division of the BBC concerned.

“At this stage, it’s for the management of the Division responsible for the programme (BBC Radio in this case) to notify me of the action they propose to take as a result of the finding, so any decision about broadcasting a correction will be theirs in the first instance (though it’s also open to me to say whether I consider the action adequate).”

As we have previously noted here in connection to the absence of a dedicated corrections page on the BBC News website, the whole point of making corrections is to ensure that audiences receive the corrected information.

One cannot but question the efficacy – and commitment to transparency – of a publicly funded complaints system which apparently does not include a mechanism to ensure that audiences are automatically informed in the most efficient manner possible of the fact that they were given misleading information, rather than the outcome being dependent upon decisions made by individual departments.