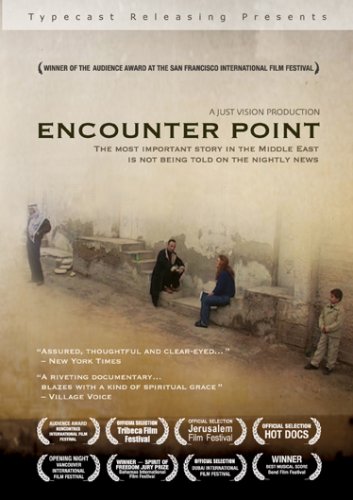

Encounter Point (2006)

Directed by Ronit Avni and Julia Bacha

Just Vision Films

Arabic, English, Hebrew

85 minutes

Rhetoric about reconciliation and non-violent resistance leading to co-existence might sound appealing, but it can create a distorted understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The documentary, Encounter Point, insists that these tactics can persuade Israel to withdraw from the disputed territories, resulting in peace between the two parties. However, by arguing that Israel’s presence in the disputed territories is the principle roadblock to peace, the film ignores the fact that Palestinian rejection of the Jewish presence in the land and their refusal to accept the right for a Jewish state to exist lie at the core of the conflict.

Directed by Ronit Avni and Julia Bacha, Encounter Point follows the stories of a South African-Israeli mother, a former settler, a former Palestinian protestor, an Israeli father, a Palestinian Christian father and a Palestinian ex-prisoner, all of whom are dealing with the loss of a loved one due to the conflict. Many of them are active with the “Bereaved Families Forum”, a dialogue group of Israeli and Palestinian families whose mission “promotes reconciliation as an alternative to hate and revenge.”

The documentary attributes the root of the conflict to the “Palestinians struggle to end Israeli military occupation and create an independent state.” The emphasis on ending the “occupation” throughout the film mistakenly emphasizes June 1967, when Israel gained control of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, as the pivotal point of the conflict. It takes the position that peace will be achieved if Israel withdraws to the pre-1967 lines. But in fact, prior to Israel’s acquisition of these territories, Arabs repeatedly rejected peace with Israel and instead attacked the Jewish state in 1948 and 1967, and Jewish communities prior to statehood.

While Encounter Point acknowledges the longevity of the conflict—“Israelis and Palestinians have been locked in a bitter conflict for generations”— it fails to consider how this fact disproves its argument about the centrality of “occupation.” In 1929, prior to the establishment of the modern state of Israel, the Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini called for the slaughter of the Jews, instigating Arab rioters to attack Jews in Jerusalem, Hebron, Tzfat, Jaffa and other areas across the country. Again, in 1936, Arabs violently revolted against Jews, protesting an increase in Jewish immigration and land purchases.

In 1947, the UN General Assembly voted in favor of a partition plan that would create two states in the Palestine Mandate, one Jewish and one Arab. While Jews accepted the resolution, Arabs rejected this proposal and instead launched an aggressive attack in an attempt to expel Jews from Israel, if not annihilate them.

The film’s failure to acknowledge the deep-rooted Arab aversion to a Jewish presence in the land even before the “occupation” perpetuates the dangerous assumption that a peaceful solution will result from a unilateral Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 lines.

To its credit, Encounter Point acknowledges the rejectionist viewpoint, as demonstrated by a scene showing injured Palestinians discussing politics at a rehabilitation center in Bethlehem. Yousef, an injured Palestinian states, “There is no such thing as peace.” When another Palestinian starts to speak about establishing a state within the 1967 lines, Yousef interjects, “Wake up! With Jews, there’s no peace.” Later, he adds, “Personally, I don’t believe in Jews in Palestine.”

However, at the end of the documentary, Yousef agrees to attend a meeting at the “Bereaved Families Forum”, implying his shift to non-violence and acceptance of a Jewish state. Regrettably, such a transformation is not representative of the Palestinian population, as indicated by a July 2011 poll conducted by Stanley Greenberg in conjunction with the Palestinian Center for Public Opinion.

According to the poll, more than 60 percent of the Palestinian population reject a two-state solution with Israel and support Hamas’ charter that calls for killing Jews.

Unfortunately, this statistic shows that all too many Palestinians are more interested in destroying Israel than in establishing their own state, and contradicts the film’s message that Palestinians seek only to remove Israel’s presence in the West Bank.

The film’s bias is further demonstrated through its prejudicial language. As former settler Shlomo Zagman speaks about his decision to move within the Green Line, the on-screen text notes, “After 23 years living as a settler in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Shlomo and his family decided to move into Israel.” The labeling of the territories as “Palestinian” suggests that only the Palestinians have a legitimate claim to the disputed territories, presupposing the outcome of future peace negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians. American policy, UN Security Council Resolution 242 and the Oslo Accords, among other agreements, all underscore that the West Bank will be divided in some way between Israel and the Palestinians.

Additionally, Encounter Point fails to acknowledge the security concerns of withdrawing to the 1967 lines. A strong body of opinion points out that these lines would be indefensible borders. Regarding the narrow nine-mile-wide corridor between the Green Line and the Mediterranean Sea, Israeli General Yaakov Amidror explains, “A future attack launched from the pre-1967 lines against Israel’s nine-mile-wide waist could easily split the country in two.” This security threat is why Resolution 242 insisted that Israel would need to establish “secure and recognized boundaries,” which would necessarily differ from the 1967 lines.

The film’s imbalanced presentation is further evidenced by its failure to condemn Palestinian terrorism. In fact, it often makes excuses or blames Israel for supposedly pushing the Palestinians to terrorism.

While Encounter Point offers the possibility that terrorism may be encouraged by Palestinian incitement rather than Israeli “occupation,” this point is glossed over and not sufficiently explored as one would expect from a serious and fair-minded documentary.

The film shows an interview, conducted between a television host and a founder of the Bereaved Families Forum, during which the host points out that Palestinian parents glorify their children who become martyrs. The Israeli representative of the Bereaved Families Forum responds, “Perhaps, we should ask ourselves, ‘How did we push an entire population to laud and praise suicide bombers?’”

When the host offers, “What if what’s pushing them has nothing to do with us? What if it is some kind of societal or cultural movement within the Arab or Muslim population? Not just here, but in the entire Islamic world,” the interviewee from the Bereaved Families Forum shakes his head in disagreement. The documentary does not pursue this important question further.

Another problematic element of Encounter P

oint is its specious comparison between Israel and apartheid South Africa. First, the film hints at the comparison when Palestinian ex-prisoner Sami Al Jundi speaks about how he gained inspiration to adopt non-violent resistance after reading Nelson Mandela’s writings in prison. Later, the film explicitly draws the parallel when Israeli Robi Damelin, originally from South Africa, where she herself fought against the apartheid system, equates Israeli treatment of Palestinians to whites’ treatment of blacks in South Africa.

As expressed by the Vanguard Leadership Group, an honor society for top students for America’s historically black colleges and universities, the use of the word “apartheid” to characterize Israel is “patently false and deeply offensive.” Arab citizens of Israel enjoy equal rights; though discrimination exists (as it does in many other democracies), Arabs vote, study at Israeli universities, and hold influential positions in the Israeli judiciary, military and government. Arabs in the West Bank and Gaza are not Israeli citizens, so they do not share all the privileges of Israeli citizenship. Instead, they elect their own leaders to administer the territories and provide political and civil rights for them.

Encounter Point’s argument for Israel to withdraw to the 1967 lines is further weakened by its acknowledgement in the final narration that Israel completely withdrew from the Gaza Strip. The film, however, fails to recognize that this unilateral withdrawal resulted in the transfer of power to Hamas, a terrorist organization that has fired thousands of rockets into Israel and whose charter calls for the murder of all Jews. Encounter Point does not acknowledge the potential danger for a similar situation to occur if Israel were to withdraw unilaterally from the West Bank.

Through the glossy rhetoric of peace and reconciliation, Encounter Point deceptively advances a political agenda blaming Israel’s presence in the West Bank for the lack of peace and consequently encouraging its audience to pressure Israel to withdraw unilaterally to the insecure 1967 lines. This distorted understanding of how to attain peace impedes efforts to reach peace because it de-emphasizes the real stumbling blocks—Palestinian rejection of a Jewish state and continued glorification of terrorists.