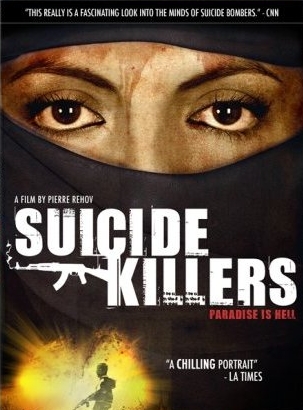

Suicide Killers (2006)

Directed by Pierre Rehov

English, Arabic, Hebrew with English subtitles

80 minutes

The roots of evil are unfathomable — yet they must be understood in order to be confronted. What, for example, motivates someone to deliberately end his or her own life in order to murder, maim, and wreak devastation upon others?

In his seventh documentary, French filmmaker Pierre Rehov takes on this seemingly impenetrable topic, delving into the aberrant phenomenon of suicide killings that has gained currency among radical Islamists over the last decade. The filmmaker investigates the motives and driving forces behind the attackers through interviews with psychologists, terrorism experts, family members, victims, and most compellingly, with failed and would-be suicide killers themselves.

The wide spectrum of perspectives — male and female, Arab and Israeli, intellectual and uneducated, victim and perpetrator — dispels the notion that there is a single cause to the problem. What does become apparent, however, is the central role Islamic societal and religious indoctrination plays in creating suicide killers.

The film opens with a masked Palestinian man in an unknown location on the Gaza Strip donning fatigues, cocking his gun, kneeling in prayer, and practicing for a mission. Abu Hazaifa, as he is labeled, a member of the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, discusses his intent to become a “shaheed” or martyr (as Arabs refer to suicide killers). The father of three children, the eldest of whom is only five years old, Abu Hazaifa expresses his hope that they will follow in his footsteps, and says that his own mother constantly prays that he and his siblings will become martyrs.

He does not fit the common assumption of a terrorist driven to his actions by a miserable, poverty-stricken existence; Abu Hazaifa emphasizes his children are well taken care of and have everything they need. Nonetheless, he states that he wants to blow himself up among Israeli civilians because of what he vaguely claims “Jews are doing to civilians.” His eagerness for his children to become “martyrs,” as well as his insistence that when he detonates himself among civilians he will not feel “sorry for any Israeli child” or “regret even if it is a nursery full of kids,” are chilling.

Equally chilling are the scenes interspersed throughout the film of shrines to the martyrs, rows of white-robed and hooded people strapped with explosive belts, and Palestinian children at a summer camp pretending to shoot guns, throw grenades, and train for missions. A camp leader explains that the youngsters learn it is their duty to carry out suicide attacks and that attackers will attain “the highest state in Paradise.” Likewise, a would-be suicide killer reveals that the button that detonates a suicide belt is known as the “key to Paradise.” Indeed, according to the film’s interviewees, the Islamic belief in martyrdom as a means to Paradise is the major motivator for suicide attacks.

Palestinian would-be and failed suicide killers, as well as dispatchers and planners of suicide missions, speak from high-security Israeli prisons. They describe their society’s adoration of those who carry out “martyrdom” operations, and express regret that their missions failed.

Women incarcerated for their roles in suicide bombings are interviewed as well. As the narrator states, what is “more disturbing than [the women’s] desire to fight is their serenity.” Their serenity is most disturbing when they describe the Muslim world’s joy after the 9/11 attacks, and when they justify killing “enemies of Islam” as “a holy act.”

“To be the parents of a martyr,” one female Hamas prisoner declares, “that is the biggest reward. It is a big honor for the family.” And several of the parents shown in the film concur. One father of two suicide killers proudly asserts that he brought up his children “to be martyrs.” His daughter proclaims that having two martyrs in the family is an honor and that they will “offer” all the children of the family, both “men and women, for martyrdom.”

It becomes clear that the radical Islamic world’s embrace of martyrdom is the result of religious indoctrination. “The Koran deals with ‘life’ with contempt and in a negative way” declares an imam in a clip shown from Hezbollah’s Al Manar Television, promising that those who sacrifice their lives for Allah will merit “an authentic and dignified life” after death.

There is one exception to the prisoners’ frightening certitude in the rightness of their quest to die killing infidels. Hamas member Arafat Rashid Morali, who abandoned his suicide mission at the last minute, discusses his pangs of conscience as he came face to face with the civilians he was about to kill. Morali describes how he turned away without hesitation when he caught sight of a mother nursing her baby. But sadly, his is the only example of human compassion among the would-be killers.

“Suicide Killers” does an excellent job showing the unremitting indoctrination of youth within a society that uses religious beliefs to fight a political battle, while at the same time also showing Muslims who do not condone this type of indoctrination, those who oppose suicide attacks and Palestinians who do not want to use violence to attain their goals.

The filmmaker explores different factors that create suicide killers — factors that take root in a culture of anti-Semitic, religious and nationalistic indoctrination.

Gazan psychiatrist Eyad Sarraj theorizes that it is the “brutal and humiliating environment of the Israeli occupation” breeding Palestinian anger and a sense of worthlessness that leads to the desire to “die in glory” rather than to “live in humiliation.”

A Hamas member incarcerated for her role in planning a suicide attack, however, brings a different perspective, emphasizing that she and her cohorts do not fight only “against the occupation” but “to spread Islam to all, everywhere.” Exactly how this goal is accomplished by suicide attacks is not explained.

Others suggest feminism is the reason women participate in suicide missions. Islamic society subjugates women, according to Eras Sekalla, president of a Palestinian women’s right organization. Various television clips showing Muslim imams putting down women prove her point. Women are pushed into the background, not allowed to make decisions and hidden behind curtains, Sekalla says. Carrying out an act of “martyrdom” — sanctioned by religious leaders and society — presumably allows women to assert themselves in this society and reap the same perceived benefits as men.

A significant portion of the film explores how sexual frustration among Muslims strictly separated from the opposite sex is channeled into the quest for martyrdom with its promise of 72 virgins in Paradise. They believe, the film suggests, that denial of earthly pleasures in this world will bring great rewards in the hereafter. Several would-be male suicide killers who profess to never having had a relationship with a woman describe the pleasures of heaven.

“Those who blow themselves up get a good bonus from God,” says one. “They marry 72 virgins.” Another reads from a Koran, grinning: “In Paradise, God places maidens in tents. They have never been touched, not by humans, not even by the devil.”

A female suicide bomber shyly smiles as she fantasizes she will be the prettiest of t

he 72 virgins in Paradise.

The film provides no single, conclusive answer as to what exactly creates a suicide bomber, perhaps because none exists. As one Islamic Jihad operative describes the motives of a suicide killer he dispatched: “She got confused with three motives: religious, national and personal. It was not only the religious motives nor the national one. She got confused with her personal feelings.”

The film’s title — “Suicide Killers,” rather than the more familiar “suicide bombers” — emphasizes the suicides’ homicidal intent and their direct impact on the victims. This impact is not lost in the film, which devotes several scenes to terrorist survivors and victims — both Arab and Jewish — as well as clips of the aftermath of such attacks.

The uniqueness of “Suicide Killers” is that it allows would-be suicide bombers and their supporters to speak for themselves. Rehov is neither seen nor heard during the movie. The camera focuses on the subjects of the film, frequently zooming in on their faces, allowing viewers to look into their eyes and creating a sense of intimacy without a third party intermediary.

Where the film is weak is in its lack of a cohesive narrative. It flits back and forth between subjects and theories in a somewhat haphazard way that is occasionally confusing. Nevertheless, the gripping nature of the topic and the exclusive footage Rehov managed to obtain are engrossing.

The roots of evil might never be fully understood, but “Suicide Killers” provides a small window into the suicide bomber’s mind, which makes this film essential viewing.