- 2.6K

- 2.6KSHARES

Peter Beinart wants us to trust him when he says the Jews can do without the State of Israel.

True, millions of Jews – Holocaust survivors, Jews who escaped oppression in the Arab world, Soviet refugees, Beta Israel from Ethiopia, and others – have understood that a Jewish state is essential to the safety of the Jewish people.

True, Jews remember the history of genocide and persecution that resulted from, and painfully highlighted the consequence of, their powerlessness over the centuries. They, along with their allies (whose numbers have included Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks), have overwhelmingly concluded that a Jewish majority in a state where they can chart their own course, and where defending Jewish lives cannot fall out of favor, is not only necessary but just.

But Beinart, a longtime anti-Israel activist, now says otherwise. To the seven million Jews in Israel, and to the roughly 90 percent of American Jews who say they are pro-Israel and that caring about Israel is an essential or important part of their Judaism, Beinart, in a new essay calling for a world without the State of Israel, argues the following: We don’t need, and shouldn’t want, the world’s one, tiny Jewish state to continue to exist. The Jews will be just fine without it. Trust me.

But between the lines, the essay screams the opposite. From start to finish, Beinart’s piece, titled “Yavne: A Jewish Case for Equality in Israel-Palestine,” misrepresents facts, conceals inconvenient truths, and plays fast and loose with ideas while purporting to tell the story of Jews and Arabs living in the Holy Land.

Whether this is a result of self-deception or an attempt to deceive his readers is beside the point. If we can’t trust Beinart to forthrightly discuss the present, why should we trust his assurances about a future utopia in which the national liberation of the Jewish people is undone, and replaced by a new country in which Hamas and Islamic Jihad are folded into the body politic?

Fast-talking a Poll Result

It might be best to start with a simple example of dishonesty in Beinart’s essay, which was published in Jewish Currents. Some of Beinart’s slippery, inconsistent argumentation requires energy and patience to unpack (but it’s worth unpacking, so don’t be deterred). His disingenuous treatment of a 2019 Israeli poll, though, is straightforward and glaring.

Consider how he describes the following survey finding, and more importantly, consider why he chooses to describe it this way:

Last year, when the Israeli Democracy Institute asked Israeli Jews what should be done with Palestinians in Area C—which comprises more than half of the West Bank—if Israel annexes that territory, the most popular answer was that they should be physically removed.

“The most popular answer,” Beinart tells his trusting audience. In fact, a distinct minority of respondents, 36 percent, said that those living in Area C should be physically removed. A substantially larger proportion, 45 percent, said they should stay. (Nineteen percent said they didn’t know.) But because the poll offered several different possible answers options for the “stay” scenario, and only one option for the “go” scenario, those in the 45 percent plurality were split into three subgroups, while the 36 percent minority remained undivided.

The original report by the Israeli Democracy Institute similarly casts the 36 percent as the “highest rate” of the possible answers – but that report, at least, lays out the results clearly for all to see. In any event, it’s not enough for Beinart to plead that he was just following the example of the poll report. He is a clever man, and he knows that Israelis who said the Palestinians should stay made up the largest group of respondents. He just didn’t want readers to know. And that’s inexcusable.

We can point to another example of such wordplay in the same passage, albeit a much more subtle one. When discussing the poll question about Palestinians in Area C, Beinart says the territory “comprises more than half of the West Bank.” Why does he speak of geographic area and not population, which would be a more informative metric? He opts for the former because Area C is, and always has been, sparsely populated by Palestinians – and because “more than half” sounds much worse than “7 percent,” which is roughly the proportion of West Bank Palestinians living in Area C.

Does that mean it’s a good thing that just 36 percent of Israelis said that only 7 percent of Palestinians should be removed from their homes? No. It simply means that Beinart, in his polemic about wresting away statehood from the Jewish people, seeks to persuade in underhanded ways.

His point in citing this poll – indeed, his point throughout the piece – is to cast Israeli Jews in as negative a light as possible. In this specific example, Beinart used the poll to support his charge that Israel theoretically “could,” in the future, start “inching” toward “policies of mass expulsion.” It is a carefully-crafted passage of such precise equivocation that it seems designed to leave the bitter aftertaste of the phrase “mass expulsion” in readers mouths, even as his muddy qualifiers fade away.

It is unclear, anyway, that Beinart actually thinks “mass expulsion” is as bad as he purports to believe – at least when it comes to Jews who might be expelled. In a section of the essay discussing Palestinian views, he cites as a “groundbreaking” and “historic compromise” a 1978 essay by Walid Khalidi, relaying, as virtual gospel, some of the Palestinian historian’s conditions for accepting a Jewish state alongside a Palestinian state. One of those conditions is that the thousands of Jews living in settlements be expelled from their homes. To Beinart, this demand wasn’t worthy of mention.

Nor does Beinart ever express concern, in this essay about how Jews would “prosper” even potentially as a minority among a Palestinian majority, about a recent poll that found more than twice as many Palestinians as Jews would choose to transfer or expel their counterparts from all the territory between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea. What type of analysis focuses on the illiberal views of some minority of Jews, but finds irrelevant those same illiberal views among Palestinians?

This discrepancy is part of a pattern of downplaying Palestinian intransigence, as we will see further below. But first, some more examples of his treatment of Israel.

New Towns for Jews and Arabs

Another straightforward example of Peter Beinart’s misinforming readers is when he claims, while approvingly relaying a quote from Israeli lawmaker Ayman Odeh, that Israel “has built ‘700 Jewish towns and not a single Arab town’ since its founding.”

In fact, Israel has established the city of Rahat, and towns including Lakiya, Hura, Kuseife, Tel as-Sabi, Ararat an-Naqab, and Shaqib al-Salam, Terabin al-Sana, Abu Karinat, and Moleda, for its Arab residents. Beinart and Odeh’s claim is simply false.

Beyond the factual error about numbers is the disingenuous idea behind Beinart’s comparison. It is a fact, after all, that hundreds of Israeli towns were established since the late 1940s, compared to only a few Arab ones. And Beinart floats that as proof of Israeli ugliness.

A cursory understanding of Israeli history is enough to recognize that the opposite is true. From its founding, Israel took in millions of Jewish immigrants who needed a home. And these Jews – the ones emerging from Europe with numbers tattooed on their arms and horrors imprinted on their psyche, those escaping persecution in Iraq without so much as a suitcase, those rejecting second class citizenship in Morocco or the boot of Soviet oppression, those fleeing from Yemen and Iran and Ethiopia, and those who were simply moved to help build a country that would serve as a home for Jews in need – all needed somewhere to live. There were not, on the other hand, a million Arab immigrants since the 40s, and so there was no need for 700 new Arab towns.

Beinart, though, chooses to represent the difficult absorption of Jewish refugees in Israel as evidence of malicious inequality, giving us yet another example of his efforts to cast Israel in the least flattering light possible, facts and context be damned. And this is the man we’re meant to trust when he says Jews have nothing to lose by eliminating the one country whose laws guarantee the absorption of Jews, and whose Jewish majority helps ensure those laws remain on the book.

Settlement Growth

Another set of straightforward misrepresentations and disingenuous claims, again designed to cast Israel as villainous, appears in the following passage:

Commentators sometimes attribute … hardening Israeli attitudes to the disillusioning effects of Palestinian violence. But over the last 15 years, largely because of Palestinian security cooperation with Israel, the number of Israelis killed by Palestinians has decreased dramatically: from more than 450 in 2002, at the height of the Second Intifada, to an average of less than 30 per year since the Second Intifada ended in 2005. (The number of Palestinians killed by Israel is far higher.) Yet Israeli support for a Palestinian state has steadily declined nonetheless. Over the last decade, in an era of relative Palestinian quiescence, the pace of settlement growth has quickened, and Israeli voters have made Netanyahu, a lifelong opponent of Palestinian sovereignty, the longest serving prime minister in their country’s history.

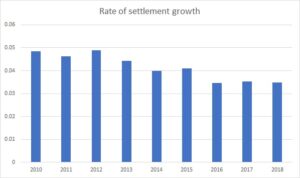

Let’s begin with Beinart’s claim that, over the past decade, “the pace of settlement growth has quickened” in spite of what he calls relative “quiescence.” Beinart’s link leads to a page on Peace Now’s website. And according to the data at that very web address, which shows the annual increase in the settler population through 2018, his claim is false. From 2000 through 2018, in fact, the rate of growth has steadily decreased, from around 5 percent per year to roughly 3.5 percent. (Peace Now does indicate there’s been an increase in the number of “construction starts” and illegal settlement outposts during that same period. But the argument Beinart relays elsewhere in his essay is that it is the number of settlers, not of buildings, that risks precluding a Palestinian state.)

The passage above is marred by other problems, too. During Beinart’s era of “relative quiescence,” there were two Gaza wars. Each of those wars was preceded by days of relentless Palestinian rocket attacks toward Israeli towns and cities. There was a “car intifada” during which Palestinian drivers turned their vehicles into deadly weapons targeting Israelis, and a “knife intifada” that saw scores of stabbing attacks against Israeli Jews. And there was yet another rebuffing of an Israeli peace offer by a Palestinian leader. By concealing these behind the phrase “relative … quiescence,” Beinart doesn’t give readers even the chance to decide for themselves if any hardening of Israeli attitudes might make sense.

Beinart’s assertion that the number of Palestinians killed by Israel is “far higher” than the number of Israelis killed by Palestinians, meanwhile, is also revealing. Buried somewhere at the webpage Beinart links to, even Max Fisher and Vox, far from a pro-Israel combination, acknowledge the fact that an Israeli killed by Palestinians is “much more likely to be a civilian than uniformed.” And when large numbers of Palestinians were killed, it was generally while “Israel was targeting Hamas and other militant groups.” Beinart, though, would prefer readers equate Jewish civilians targeted for murder with Palestinians militants killed, and civilians tragically caught in the crossfire, during strikes against terror groups.

That Beinart tends toward seeing Palestinian violence against Jews as legitimate, and Israeli attempts to stop such violence as illegitimate, is neatly underscored by a passage in the essay that euphemizes the former as “armed struggle” and the latter as “brutality.” He refers to an American peace plan that produced “a spike in Palestinian support for ‘armed struggle,’” before continuing,

And if armed struggle breaks out, Israeli and diaspora Jews who already support policies that inflict violence on Palestinians will interpret a violent Palestinian response as a license for ever greater brutality.

Apologia for Palestinian Violence

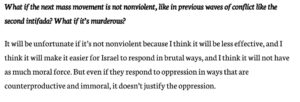

Beinart says the killing of Israelis in new wave of suicide bombings would be “unfortunate”—because it would be “less effective.” Israeli attempts to end the violence are cast as “brutal.” (Interview with Ben Sales, July 9)

That’s not the only way Beinart’s essay downplays Palestinian terrorism. In one passage, he blames Jewish immigrants for Palestinian attacks on Jews, while also concealing that these attacks were attacks on Jews: “in the late 1920s and ’30s, under British colonial rule, increased Jewish immigration provoked increased violence between Palestinians and Jews” (emphasis added).

It’s clear that Beinart wouldn’t likewise blame immigration from Latin America for “provoking” white nationalist attacks on immigrants in the U.S. What’s less clear is why he feels comfortable using such language to describe attacks on innocent Jews.

Notwithstanding Beinart’s reference to “violence between Palestinians and Jews,” The Peel Commission Report, an official British report that looked into the unrest in 1930s Palestine, refers in no uncertain terms to Palestinian Jews being attacked. “As in 1933,” the report explains, “it was not only the Jews who were attacked, but the Palestine Government.” A subsequent British report likewise fleshes out Beinart’s “violence between Palestinians and Jews” with accounts such as the following:

Arabs of Jaffa murderously attacked Jewish inhabitants of the town and Arab raids were made on five Jewish rural settlements; the disorders were suppressed by the police and military forces. Forty-seven Jews were killed and 146 wounded, mostly by Arabs, and 48 Arabs were killed and 73 wounded, mostly by police and military action.

Notable among the attacks purportedly “provoked” by Jews were the 1929 massacres of Jews in Hebron, Jerusalem, and Safed, which killed over 100 innocents, and whose grisly details are almost unimaginable. To describe it as “a vicious attack by Arabs on Jews accompanied by wanton destruction of Jewish property,” as yet another British investigation into anti-Jewish violence concluded, is to put it mildly.

This is how the New York Times recounted the events of 1929, after a similar orgy of anti-Jewish violence in 1938: “Not since the riots of 1929, when Arabs fell on Jewish men, most of whom were rabbinical students, as well as women and children, in the ancient towns of Hebron and Safed, has there been in Palestine such a slaughter as the attack of last night.”

When Beinart does eventually get around to naming “Palestinian uprisings” as the source of violence in 1929, he responds to the murders with a shrug: “In 1929 and 1936, Palestinian uprisings turned violent. But in this, too, Palestinians were hardly unusual among peoples fighting colonialism.”

Yet again, we should ask the question: if Beinart dismisses the murder of Jewish toddlers, dismembered extremities scattered on floors, the burnt bodies of women tied to window grilles in charred houses – these are just some of the scenes of horror described by eyewitnesses at the time – as “hardly unusual,” why should we trust this man’s vision for the future? What harsh words, like “hardly unusual,” should we expect from another of his essays in the event that his political experiment turned out, despite his assurances, to be dangerous for Jewish lives?

The “Mini-State”

Consider, too, how Beinart early in his piece relates to Hamas, the Islamist terror group that rules the Gaza Strip, and to other Palestinian leaders who have opposed Israel’s existence:

For most of the 20th century, Palestinians pursued a state of their own in the entirety of the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. But by the 1970s, Palestinian intellectuals began admitting publicly that this long struggle had failed. In a bitter concession to reality, they proposed that Palestinians instead pursue what they called a “mini-state” in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. In 1988, when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) recognized Israel, this became its official position. Even the Islamist movement Hamas—which has not recognized Israel—has repeatedly embraced the “mini-state” as the basis for a long-term truce.

Beinart says that the Palestinian intellectual class “by the 1970s” had moved on from their mission to violently eliminate Israel and replace it with a Palestinian state. They were content instead, he indicated, with control over the West Bank and Gaza Strip, areas that had been cleansed of Jews in 1948 and that came under Israeli control in 1967. Hamas, too, “embraced” the idea, he continues. And as proof, Beinart provides a link to a page that similarly claims Fatah and the PFLP, two Palestinian factions, called for such a “mini-state” after 1973.

This is specious. It was in 1980, after all, that Yasir Arafat, the head of Fatah, and of the Palestinian national movement at large, declared that “Peace for us means the destruction of Israel.”

At any rate, when some of the Palestinian leadership, including intellectuals among them, reversed course from their rejection of a Palestinian “mini-state” in the 70s, it wasn’t because gave up on their demand to destroy Israel.

On the contrary, in 1974, the Palestine National Council, which included Fatah and the PFLP, was explicit about their continued demand that Israel be forcefully wiped off the map. The Council’s 10-Point Plan, adopted in June 1974, asserted that the Palestinian leadership will “struggle against any proposal for a Palestinian entity the price of which is recognition, peace.” Yes, Palestinians would be willing to establish an authority in any territory “liberated” from Israeli control – for example the West Bank and Gaza Strip – but that would be used as a bridgehead for the continued fight to destroy Israel: “Any step taken towards liberation is a step towards the realization of the Liberation Organization’s strategy of establishing the democratic Palestinian State specified in the resolutions of the previous Palestinian National Councils.” In other words, a Palestinian state to replace Israel.

If that wasn’t clear enough, the Plan continued: “Once it is established, the Palestinian national authority will strive to achieve a union of the confrontation countries, with the aim of completing the liberation of all Palestinian territory.”

Beinart goes so far as to lump modern-day Hamas into the “mini-state” group, cherry-picking some articles from the aughts to underscore his point. Were he interested in being forthright with readers, he would have let them know that Hamas, too, has made clear it would accept territory in the West Bank and Gaza only as a bridgehead to destroying Israel. Any truce would entail “no concessions over any part of the land of Palestine,” Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh explained in late 2010. The following year, Hamas political leader Mahmoud al-Zahar said that the Jews “have no place among us…and no future among the nations.” Another Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar, more recently argued that Palestinians “can’t give up one inch of the land of Palestine.” And Haniyeh has made perfectly clear the meaning of such sentiment: “Palestine is from the [Mediterranean] Sea to the [Jordan] River! And we shall never, never, never recognize Israel.”

So much for the “bitter concession” Beinart tries to sell as a “historic compromise” – all for the purpose, it seems, of downplaying the extremism and threat posed by Hamas, an antisemitic group known for its suicide bombs targeting Jewish civilians in pizzerias, cafes, and dance clubs.

No argument, not least one that demands the political disempowerment of the Jewish people, should be based on distortions that exaggerate the shortcomings of one people involved while downplaying the faults of the other, as Beinart does throughout his essay.

Nazis and Equality

The overall framework of the essay is no less problematic than its collection of misleading passages (and the list above is hardly comprehensive). Beinart begins and ends his piece by dismissing concerns about his proposed new regime as, essentially, so much Jewish pathology. The reason Jews around the world would be skeptical of Beinart’s vision – a vision that Dan Shapiro, a normally soft-spoken expert on the region, dubbed “utopian nonsense” – is that they are all blinded by the trauma of the Holocaust.

The unspoken force behind Jewish support for Israel, Beinart insists to open his piece, is that “opposing a Jewish state means risking a second Holocaust.” But this is trickery, he continues. “Through a historical sleight of hand that turns Palestinians into Nazis, fear of annihilation has come to define what it means to be an authentic Jew.”

He revisits this thought at greater length in his conclusion. “The depiction of Palestinians as compulsive Jew-haters—and the corresponding belief that anything short of Jewish statehood constitutes collective suicide—stems less from Palestinian behavior than from Jewish trauma.” And elsewhere: “The belief that Jews in the land of Israel risk genocide without a Jewish state is central to what it means to be a Zionist today.”

This “Holocaust lens,” Beinart insists, is responsible for all sorts of crimes. What else but Jewish trauma and sleight of hand, he suggests, could explain skepticism of claims that Hamas leaders, the likes of whom have referred to “Jewish filth” and who openly say Jews corrupted European societies with “usury, the worship of money, extreme miserliness, and bribery,” in fact want to live in peace with the Jews?

Beinart’s own broad brushing of Jews and wild hyperbole is less harsh that that of Hamas, but it is nonetheless alarming. The Holocaust lens supposedly “makes Jews who recognize Palestinian humanity appear naïve, if not traitorous.” It supposedly “turns anyone who takes up the Palestinian cause into a Nazi sympathizer, guilty of antisemitism until proven innocent.” It must be this same lens, Beinart argues, that prevents more Jews from embracing his solution of Israel’s dissolution.

These are grave and insulting charges, particularly coming after Beinart says, early in his piece, that this set of views stemming from a Jewish Holocaust pathology is “rarely spelled out.” Apparently, it’s the caricature of modern Jews in Beinart’s head that spell it out for him.

Yes, Beinart has diagnosed the problem, and it is nothing less than contemporary “Jewish identity,” an identity that he insists “equates Palestinian equality with Jewish genocide.”

(An aside on that last quote: Nearly 20 times throughout his essay, Beinart uses the word “equality” as a stand-in for his vision of eliminating Israel. This repetition might make for good advertising copy. But it is absurd to suggest that equality could only mean Beinart’s vision of one state – as if equality will elude us until Pakistan and India unite, and as if anyone who might reject rejoining Ireland with the United Kingdom is rejecting “equality” itself.)

At any rate, should Beinart’s assessment – that Jews are hesitant to toss away their state because they have “have retroactively projected Nazism’s exterminationist program on Palestinian opposition to pre-state Zionism” – be taken as a serious argument?

Is genocide the only tragedy that Jews could possibly worry about? Is extermination the only possible consequence of taking from the Jewish people the ultimate responsibility for their own self-defense? Of course not. We’ve already seen above examples of abuse of Jews in pre-state Palestine that fall short of genocide. So should we, like Beinart, shrug at “mere” massacres like the ones that took place in 1929? (It is worth noting that Beinart also explains away a Palestinian leader’s warm alliance with Hitler as “hardly unique.”) And if enfranchising Islamic Jihad within Israel instead of across a border in Gaza might make it easier to kill Jews in suicide bombings, should the threat of those murders not matter, since they fall short of genocide?

And, on the other hand, is genocide not something a healthy people should concern themselves with? Beinart’s essay seems almost to scoff at those who would utter the phrase Never Again. But most Jews in the world do not. (And why should they, after Rwanda and Cambodia and Darfur?)

On Sovereignty

At the end of his piece, Beinart tries to make the case that sovereignty shouldn’t be so important for Israeli Jews. “It is generally taken as a given in mainstream Jewish discourse that without sovereignty, Israel’s Jews would face mortal danger,” he says. And that fear of mortal danger – supposedly a result of the Holocaust lens – is the only reason Israeli Jews wouldn’t want to give up sovereignty. But they are wrong about that, Beinart insists, and so they shouldn’t insist on sovereignty.

This comes as a jarring turnaround in an essay that some paragraphs earlier treated sovereignty as an important and acceptable value – to Palestinians, that is. Beinart approvingly quotes Khalidi, the Palestinian historian, insisting on sovereignty. The prerequisite for any Palestinian state alongside Israel, Beinart argues through Khalidi, “is the concept of Palestinian sovereignty. Not half-sovereignty, or quasi-sovereignty or ersatz sovereignty. But a sovereign, independent Palestinian state.”

Beinart punctuates the point: “To this day, Palestinians overwhelmingly oppose restrictions on the sovereignty of a future Palestinian state.” Somehow, none of this this talk about Palestinian demands for sovereignty are accompanied by admonishments by Beinart about distorting “lenses,” or about the desire for sovereignty being the result of the Palestinian dehumanization of Jews.

It is the Jews, alone, whose desire for sovereignty is suspect.

And they have little to lose in giving up Israel, Beinart continues. Beinart’s new state could still be a Jewish home, he says, even if the country inevitably “trimmed” – and by that he means eliminates – the Law of Return that offers Jews around the world citizenship in Israel, which is a raison d’etre of the Jewish state:

Trimming the Law of Return need not prevent Israel-Palestine from being a Jewish home. What’s crucial, if it is to remain a refuge for Jews, is not that a Jew from New York can land in Tel Aviv and become a citizen on day one. It’s that the state enshrine in its constitution the obligation to be a haven for any Jew—and yes, any Palestinian—in distress.

But Beinart doesn’t say who, in his new state, would decide what constitutes a Jew or Palestinian in distress. Might Palestinians feel it is against their self-interest to tilt the country’s demographics in favor of Jews by, say, allowing into the country Jews fleeing antisemitism in France? How easy would it be for a Palestinian gatekeeper to demur, saying a Jew in a first-world European country couldn’t possibly be in distress. Would Jews, for their part, accept that the grandchildren of Palestinian refugees in Germany are in distress if Palestinians insisted they were?

(Beinart might counter that this is a cynical take, and that the better angels of all sides would naturally rise to the surface in the state he imposes. If so, he might be reminded of the author who wrote that “Jewish immigration provoked … violence” against Jews in the 1920s and 1930s.)

Demographics matter for peoples that have experienced oppression as minorities. Beinart might not think this should be a concern for Jews and Arabs in his state, but the Jews and Arabs who live in the Middle East certainly think it is.

And there’s good reason for that. Although Beinart suggests Jews shouldn’t worry about being the minority population in his state, since their rights could be protected, for example, by legislation that could only be overturned by 90 percent of the legislature, or since their corner of the Middle East could be just like Belgium, these arguments miss at least one important point:

Ruling systems can change. Indeed, that’s the very point of his essay, in which he argues that the democratic and Jewish state should cease to exist, despite that idea being anathema to Israelis. If Beinart wants us to believe it’s realistic to tear up the constitutional foundation of Israel, despite the wishes of the vast majority of Jews there, why wouldn’t it be all the more realistic that a new entity in which Jews are a minority would toss out whatever constitutional safeguards he fantasizes about?

There are other questions with no good answers. Beinart’s utopia, alas, would be in the real world. And like it or not, in the real Middle East there is an urgent need to consider the regional security situation – or to put it bluntly, to have an army. If the Jews were a minority in the state, or lived in some Autonomous Levantine Oblast within the state – two scenarios that Beinart envisions as possibilities – who would be in charge of the state’s army? Who would decide how hard the country should work to prevent, say, Iranian money from flowing to Islamic Jihad or other questionable Palestinian groups? Who would decide how to address threats from Hezbollah, or whether to respond to cross border attacks on Jewish towns? Would it be in the new country’s interest to defend its cold-peace partner to the east, the Kingdom of Jordan, in which more than half the population is believed to be Palestinian, from an internal Palestinian revolt? Or, rather, might those in charge prefer to help that revolt and scrap the current Jordanian regime?

There are countless other contingencies in which Beinart’s utopia would be sharply divided along ethnic lines. On such life-and-death questions, Beinart punts: Just trust me.

Beinart wants us to trust, too, that in his future utopia Hezbollah, Hamas, obscene levels of antisemitism in the Arab world, the fantasy of sending the Jews “back where they came from,” and other such inconveniences, might dry up under his regime.

But how is it that the same man who can breezily imagine such a utopia can’t also bring himself to imagine, for example, that the current array of Jewish settlements in the West Bank might not preclude a two-state solution? Or that a functioning Palestinian state on 95 percent of the West Bank, which he dismisses as impossible in his essay, is actually possible? Or that a Palestinian state with some limits to its sovereignty might work just as well for Palestinians as he envisions Jewish non-sovereignty working for Jews?

These are the scenarios that Beinart insists are non-starters. And the thought that Israel might insist on them, he explains, is what demanded his prophetic vision of a one-state solution. But those scenarios are no less realistic than the unitary state he prescribes. To the contrary, they are as easy to imagine as Mahmoud Abbas’s signature on the peace offer floated by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.

It’s just that Peter Beinart doesn’t want to imagine it. And that’s because, although he insists his dream of wiping the Jewish state from the map is an authentically Zionist vision, those words are just a flimsy cover for the fact that he, unlike an overwhelming majority of Jews worldwide, is an anti-Zionist.