Two news articles, published five years apart but referencing the same historical event, paint a damning picture of a recent decline in New York Times standards.

The event occurred in May 1948. Only days before the leaders of the Jewish community in British-ruled Palestine were to declare the establishment of the State of Israel, it was still unclear whether President Harry Truman would side with his Secretary of State, George C. Marshall, who opposed recognition of the Jewish state, or with his senior advisor Clark Clifford, who urged Truman to follow his impulse in favor of recognition.

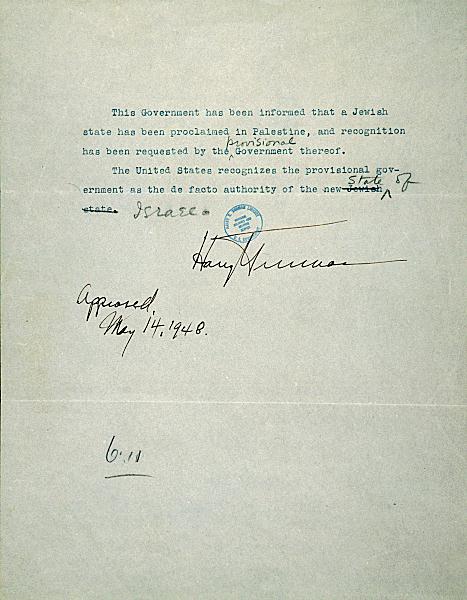

The dramatic debate was settled only hours before the modern state of Israel came into formal existence. At 6:11 P.M. in Washington, D.C., or just 11 minutes after the midnight rebirth of the Jewish state, Truman’s press secretary read the following statement:

The dramatic debate was settled only hours before the modern state of Israel came into formal existence. At 6:11 P.M. in Washington, D.C., or just 11 minutes after the midnight rebirth of the Jewish state, Truman’s press secretary read the following statement:

This government has been informed that a Jewish state has been proclaimed in Palestine, and recognition has been requested by the provisional government thereof.

The United States recognizes the provisional government as the de facto authority of the new State of Israel.

The New York Times referred to this presidential statement twice in the past five years, and the way the did so exposes an unfortunate decline in the newspaper’s standards. In both articles, reporters mentioned recent Palestinian attempts to cast a last minute change in the language of the statement — one of the letter’s two references to “Jewish state” was changed to “State of Israel” — as supposedly showing that Truman did not support the idea of a Jewish state. But while the earlier article gave some clarifying context that suggested Palestinian leaders are misusing the letter, the more recent piece relayed the misinformation with no qualification, leaving New York Times readers severely misinformed about Truman’s position.

Palestinian negotiators have long refused to recognize Israel’s Jewish character, saying that it would negate the Palestinian refugees’ demand for the right to return to their former homes and would be detrimental to the status of Israel’s Arab citizens.

In an attempt to bolster the Palestinian argument, [Saeb] Erekat on Monday produced a copy of a letter signed by President Harry S. Truman on May 14, 1948. In its original form, it recognizes the provisional government of the new Jewish state, but the typed words “Jewish state” in the second paragraph have been crossed out and replaced with the handwritten “State of Israel.”

Shlomo Avineri, a professor of political science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said Mr. Erekat was misinterpreting the American president’s intention. According to Mr. Avineri, the Truman letter had been prepared hours before Israel declared its independence, before the new country had chosen its name.

It was later corrected by a Truman adviser, Clark M. Clifford, after the declaration of independence in order to call the country by its name, not to deny its Jewish character, Mr. Avineri said.

In short, the reporter did her job in reporting what the Palestinian official said while simultaneously providing readers with the basic information they need to understand the story.

On recognition of Israel as a Jewish state, Mr. Abbas said, “This is out of the question,” noting that Jordan and Egypt were not asked to do so when they signed peace treaties with Israel. He presented a 28-page packet he has been distributing widely that included a 1948 letter signed by President Harry Truman in which “Jewish state” was crossed out and replaced by “State of Israel….”

Rudoren says nothing more about the letter. Her article, in other words, gives the distinct impression that the late American president and the current Palestinian one are on the same page when it comes to opposing the Jewish state, when in fact the opposite is true.

When CAMERA contacted Rudoren to call for a published clarification, she replied that there was no need to point out that Abbas was misrepresenting the letter because “those who know” the facts can reach their own conclusions.

Rudoren also cited space constraints to explain why she failed to educate readers about the letter, as her colleague appropriately did five years earlier. But space seems to constrain only when it’s convenient for the reporter. After all, she found room in her article about Iran to criticize the Israeli minister, although it was 250 words longer than the one that relayed Abbas’s distortion.

An editor in The New York Times standards department was hardly more interested in clearing the record. Abbas actually did show people the Truman letter, he argued, so there is nothing to correct. But this, too, is

a principle that the newspaper is willing to turn on and off as they please.

Consider the case of the New York Times‘s September 2003 obituary of Israeli ambassador Simcha Dinitz. That obituary accurately cited a book about Kissenger, but the newspaper later published an “editors’ note” because it saw the cited material as potentially misleading.

The obituary asserted that

In “The Secret Conversations of Henry Kissinger” (Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Company), Mr. Golan wrote that Mr. Kissinger duped Mr. Dinitz into telling Israel the shipments were being delayed by the Pentagon. Only after the Soviet Union resupplied Egypt and Syria did the main American airlift get under way.

Two weeks later, the editors’ note clarified,

The article asserted that Mr. Dinitz had been duped by Mr. Kissinger into believing that the Pentagon was the cause of the delay, and it cited a 1976 book, “The Secret Conversations of Henry Kissinger,” by Matti Golan, an Israeli journalist, as the source of this analysis. The Times should have sought verification of that account. In recent years, fresh examinations of the Israeli-United States diplomacy in that period, including Mr. Kissinger’s memoirs and “Peace Process,” by the former National Security Council official William Quandt, have painted a more complex picture. They report that Mr. Dinitz was not duped by the United States but in fact negotiated vigorously in the face of the American concerns.

For Douglas. Please inform Bevin or other responsible official Brit Govt that we have reason to believe that provisional govt of new Jewish state will make request at once for recognition and that in present circumstances we feel that we should grant recognition to Jewish provisional govt as de facto authority of Jewish state. (Emphasis added)