The Harvard Crimson has published an anonymous statement by its Editorial Board in favor of the notorious Boycott, Divest and Sanctions campaign (BDS) against Israel: In Support of Boycott, Divest, Sanctions and a Free Palestine. Despite the editorial’s portentous style, as a Harvard alumnus (GSAS 1987) I do feel it’s important to respond in an instructive way, since there seems to be much these Harvard students are unaware of.

The fundamental problem is encapsulated in the editorial’s headline, which links the BDS campaign to a free Palestine, and thereby – unintentionally – undermines the entire argument of the Crimson and the BDS movement as well. For history shows that Israel has agreed to a “free Palestine” multiple times, only to be vetoed by the Palestinians.

In other words, why bludgeon Israel with a BDS campaign if the Israelis have repeatedly accepted a Palestinian state? Perhaps those in favor of attacking Israel are ignorant of this history, or perhaps creating a Palestinian state is not as important to them as destroying the Jewish state.

Either way, the history is worth repeating. As the legendary Israeli diplomat Abba Eban once said about relations between the Arabs and Israel, “The Arabs never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity,” and there have been many statehood opportunities that Palestinian leaders have wilfully missed. Unfortunately, what usually follows these missed Palestinian opportunities for peace are violent attacks against Israeli civilians, such as the 1948 War and the 2000 Intifada, in which thousands of Israelis were needlessly murdered.

In accord with this, at least three times the Palestinians have refused statehood when it was offered to them. Here are the details:

1. In 2008, after extensive talks, then Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert met with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and presented a comprehensive peace plan. Olmert’s plan would have annexed the major Israeli settlements to Israel and in return given equivalent Israeli territory to the Palestinians, and would have divided Jerusalem.

Numerous settlements including Ofra, Elon Moreh, Beit El and Kiryat Arba would have been evacuated, and Hebron would have been abandoned. Tens of thousands of settlers would have been uprooted. Olmert even says preliminary agreement had been reached with Abbas on refugees and the Palestinian claim to a “right of return.”

Olmert recounted much of this in an interview with Greg Sheridan in the Australian newspaper:

From the end of 2006 until the end of 2008 I think I met with Abu Mazen more often than any Israeli leader has ever met any Arab leader. I met him more than 35 times. They were intense, serious negotiations.

On the 16th of September, 2008, I presented him (Abbas) with a comprehensive plan. It was based on the following principles.

One, there would be a territorial solution to the conflict on the basis of the 1967 borders with minor modifications on both sides. Israel will claim part of the West Bank where there have been demographic changes over the last 40 years…

And four, there were security issues. [Olmert says he showed Abbas a map, which embodied all these plans. Abbas wanted to take the map away. Olmert agreed, so long as they both signed the map. It was, from Olmert’s point of view, a final offer, not a basis for future negotiation. But Abbas could not commit. Instead, he said he would come with experts the next day.]

He (Abbas) promised me the next day his adviser would come. But the next day Saeb Erekat rang my adviser and said we forgot we are going to Amman today, let’s make it next week. I never saw him again. (Nov. 28, 2009)

And this is not just a self-serving claim by Olmert – Abbas, in an interview with Jackson Diehl of the Washington Post, confirmed the outlines of the Olmert offer and that he turned it down:

In our meeting Wednesday, Abbas acknowledged that Olmert had shown him a map proposing a Palestinian state on 97 percent of the West Bank — though he complained that the Israeli leader refused to give him a copy of the plan. He confirmed that Olmert “accepted the principle” of the “right of return” of Palestinian refugees — something no previous Israeli prime minister had done — and offered to resettle thousands in Israel. In all, Olmert’s peace offer was more generous to the Palestinians than either that of Bush or Bill Clinton; it’s almost impossible to imagine Obama, or any Israeli government, going further.

Abbas turned it down. “The gaps were wide,” he said. (May 29, 2009)

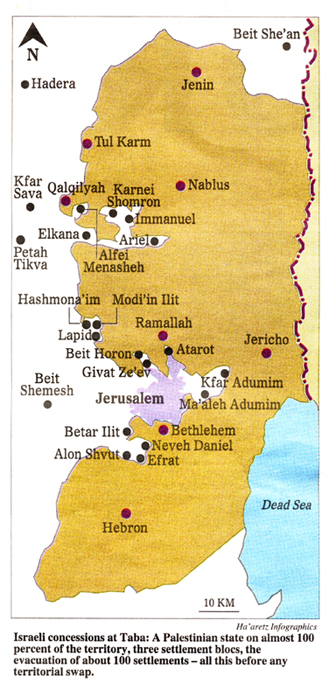

Ha’aretz published Olmert’s map, showing a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza with a free passage route to connect them. The map, which also showed the Israeli territory that would have been swapped with the Palestinians in return for annexing some Israeli settlements to Israel, is reproduced below:

Despite the vast concessions the plan required of Israel, Prime Minister Barak accepted President Clinton’s proposal, while Arafat refused, much to the surprise and consternation of the Saudi representatives to the talks. Instead of signing a peace agreement to finally end the conflict, Arafat returned home and launched a new terror campaign against Israeli civilians (the Second Intifada), featuring numerous terrible suicide bombings targeting buses, restaurants, schools, etc.

Despite the violence, Prime Minister Barak continued to negotiate to the end of his term, culminating in an Israeli proposal at Taba which extended the Clinton proposal. Barak offered the Palestinians all of Gaza and most of the West Bank, no Israeli control over the border with Jordan or the adjacent Jordan Valley, a small Israeli annexation around three settlement blocs balanced by an equivalent area of Israeli territory that would have been ceded to the Palestinians. As chief US negotiator Ambassador Dennis Ross put it in a FoxNews interview:

… the Palestinians would have in the West Bank an area that was contiguous. Those who say there were cantons, completely untrue. It was contiguous… And to connect Gaza with the West Bank, there would have been an elevated highway, an elevated railroad, to ensure that there would be not just safe passage for the Palestinians, but free passage. (Fox News, April 21, 2002)

According to Ambassador Ross, Palestinian negotiators working for Arafat wanted him to accept the Clinton Parameters, but he refused. In response to Brit Hume’s question as to why Arafat turned these deals down, Ross said:

Because fundamentally I do not believe he can end the conflict. We had one critical clause in this agreement, and that clause was, this is the end of the conflict.

Arafat’s whole life has been governed by struggle and a cause. Everything he has done as leader of the Palestinians is to always leave his options open, never close a door. He was being asked here, you’ve got to close the door. For him to end the conflict is to end himself.

Here’s the Taba map proposed by Israel, which was once again turned down by Arafat:

3. UN Resolution 181, the Partition Resolution, passed in November 1947, called for the creation of a Jewish state and an Arab state in the land which at that point was controlled by the British-run Palestine Mandate. All the Arab countries opposed the resolution, voted against it, and promised to go to war to prevent its implementation. Representing the Palestinians, the Arab Higher Committee also opposed the plan and threatened war, while the Jewish Agency, representing the Jewish inhabitants of the Palestine Mandate, supported the plan.

The Arabs and the Palestinians were true to their word and did launch a war against the Jews of Palestine, violating both Resolution 181 and the UN Charter. Much to the surprise of the Arab side, the Jews were able to survive the initial onslaughts and eventually win the war.

The fundamental fact remains that had the Arabs and the Palestinians accepted the Partition Resolution and not violated the UN Charter by attacking Israel, there would be a 74-year-old Palestinian state today next to Israel, and there would not have been a single Palestinian refugee.

Just as today, it seems that even in 1948 the Arab side was more concerned with opposing and attacking the Jewish state than with creating a Palestinian state.

I hope the Crimson will see how wrong its editorial is and withdraw it. At a minimum I hope its anonymous authors will take responsibility for the views they have expressed.

I call on all members of the Harvard community, including its current leadership, to make clear their righteous opposition to BDS’s antisemitism and those organizations who support it.