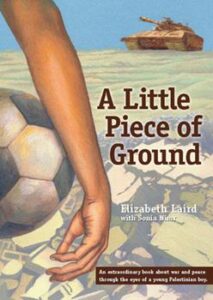

Elizabeth Laird is a renowned British children’s author, twice nominated for the prestigious Carnegie Medal. Ironically, it is her ability to tell a gripping story with vividly realized Arab protagonists that makes her novel A Little Piece of Ground so powerful – and so pernicious. (The metaphoric title reveals the author’s bias: Just as Israeli soldiers deny the boys of Ramallah “a little piece of ground” for soccer practice during the Second Intifada, so Israel denies the Palestinians their “little piece of ground.”)

Elizabeth Laird is a renowned British children’s author, twice nominated for the prestigious Carnegie Medal. Ironically, it is her ability to tell a gripping story with vividly realized Arab protagonists that makes her novel A Little Piece of Ground so powerful – and so pernicious. (The metaphoric title reveals the author’s bias: Just as Israeli soldiers deny the boys of Ramallah “a little piece of ground” for soccer practice during the Second Intifada, so Israel denies the Palestinians their “little piece of ground.”)

The book was recently listed as required reading for sixth grade in the Newark, New Jersey public schools, a choice that has been challenged by the Zionist Organization of America.[1] This isn’t the first time the book has raised hackles.

Written in collaboration with Palestinian teacher Sonia Nimr, A Little Piece of Ground met with controversy from the moment it was published in Britain in 2003. Phyllis Simon, co-owner of a Vancouver, Canada, bookstore, urged Laird’s publisher (Macmillan) to reconsider the book, pointing out that “there is not even one mildly positive portrait of an Israeli in the entire book. . . . A Little Piece of Ground . . . is for children, the overwhelming number of whom clearly haven’t a clue about this conflict, and thus depend on books like this for the opinions they form about what goes on in the Middle East.”[2]

Laird’s answer was disingenuous. “The book is written through the eyes of a 12-year-old who just sees men with guns,” she wrote. “It would not have been true to my characters to do otherwise.”[3]

Perhaps, but who made the decision to paint the Middle East conflict exclusively through the eyes of a twelve-year-old Arab boy living in Ramallah during the Second Intifada? Karim sees his father humiliated at checkpoints; not only has he no idea why the Israelis have set these up in the first place, it’s a question he wouldn’t think to ask. Karim and his friends are confined inside by endless curfews which to them seem arbitrary, and there is no voice in the novel to explain them. Soldiers damage his school; are they just throwing their weight around, or are they looking for stashes of weapons? The reader isn’t told.

In fact, Laird never explains anything the soldiers do. What she lavishes her considerable stylistic gifts on is depicting Israeli soldiers not as what they really are — teenage boys in tanks — but as tanks incarnate:

The Israeli tank that had been squatting at the crossroads just below the apartment block for days now had moved a few metres closer.[4]

He could imagine the great armoured machines lying down there, like a row of green scaly monsters, crouched waiting to crawl back up the hill and pin the people of Ramallah down in their houses again . . . .[5]

Language like this dehumanizes and demonizes Israeli soldiers. As mutant green scaly monsters, they squat, crouch, crawl and pin the people of Ramallah down.

One can only imagine the outcry if an American author employed similarly loaded terms to Black youths in an urban gang: “She could imagine the great hulking panthers, crouched behind the parked cars waiting to pounce on any passerby who neared their hiding place.” Caricaturing Israelis in the same way, though, gets a pass.

Laird makes no moral distinction between aggressive and defensive violence. She cites a news report that “Israeli troops shelled a refugee camp in Gaza . . . killing nine Palestinians, including a three-year-old child,”[6] but doesn’t care to disclose why the IDF might have shelled that camp. In 2002, 17 rockets and 455 mortar shells were fired at Israel from Gaza, and in 2003 there were at least 123 rockets and 514 mortars fired.[7] But to Laird, neutralizing rockets and mortars to protect the lives of your civilian population is morally equivalent to shooting civilians in a café.Nor does the novel really care about Israeli victims of terror. When terrorist operations are mentioned, the novel’s tone – heightened and sympathetic when Arab victimhood is reported – is oddly flat: “Since a Palestinian gunman had shot two people in an Israeli café two weeks ago, the Israelis had set up another curfew, which meant that the whole city had been locked down.”[8] Jewish victims are noticed only in passing, effectively erasing Jewish suffering.

Although association does not necessarily imply collaboration or even agreement on political issues, it perhaps bears noting that Laird’s husband worked in the 1970s for UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Administration, created in the aftermath of the 1948 war exclusively for the benefit of Arab refugees (though not of Jewish refugees from Arab lands). UNRWA is notorious for its pro-Arab bias and its staff for cooperation with terrorist groups like Hamas and Fatah.

[1] Susan R. Eisenstein, “Newark School District adds anti-Israel book to sixth-grade curriculum ,” October 25, 2022. https://www.jns.org/newark-school-district-adds-anti-israel-book-to-sixth-grade-curriculum/

[2] Teacher’s Guide for A Little Piece of Ground, p, 7.

[3] Teacher’s Guide, p. 9.

[4] Laird, pp. 4-5 (my emphasis).

[5] Laird, p. 12 (my emphasis).

[6] Laird, p. 9.

[7] Figures from Israel Security Agency. Although Laird’s novel was published in 2003, it bears noting that the Israeli death toll from the Intifada was 1000+, and many people were maimed. These facts are invisible in A Little Piece of Ground.

[8] Laird, p. 5