The BBC claims to abide by detailed Editorial Guidelines, and has a formal complaints process as recourse for news consumers who feel that these guidelines have been violated. In theory, these measures are meant to ensure the influential British broadcaster adheres to ethical norms of journalism. But unfortunately, they have not prevented it from repeatedly transmitting skewed and inaccurate reports on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

To its credit, however, the BBC has recently made important changes to an online article in response to a formal complaint filed by CAMERA.

The complaint pointed to outrageous misrepresentations and omissions in the May 7 article, “Israelis from Iraq remember Babylon.” The piece painted a highly misleading picture of “an easy, happy life” for Jews in Iraq and practically ignored the actual record of persecution faced by that population. Most egregiously, the piece failed to mention the Farhoud, a brutal anti-Jewish massacre that occurred in 1941.

After an initial refusal by the BBC News Web site to amend the article and CAMERA’s subsequent appeal to the BBC Editorial Complaints Unit (ECU), an editor told CAMERA: “On further consideration, we have made some changes to the report.” The ECU later upheld CAMERA’s complaint with respect to the accuracy of the piece, agreeing that it “had shortcomings on the facts.”

One of the key changes was the addition of information on the 1941 massacre:

But, while anti-Jewish sentiment flared up after the creation of Israel and the subsequent Arab-Israeli war in 1948-49, discrimination and attacks on Jews were part of life in Iraq.

In the most notorious incident, mobs rampaged through the Jewish district of Baghdad killing an estimated 170 Jews in 1941, in what became known as the Farhoud massacre.

The BBC also added the word “fled” to describe the departure of Jews from Iraq. This addition is significant because the article initially said only that the Jews “left” Iraq — a euphemism that hardly describes the duress, pressure and even expulsions that caused the exile.

The BBC further suggested that it would soon publish a feature article to provide readers with another (and hopefully more accurate) look at the plight of Jews forced from their homes in Arab countries.

The broadcaster should certainly be commended for making significant additions to the article and planning to revisit the issue. Still, the fact that such a skewed piece was published in the first place is cause for concern. The following paragraphs discuss the earlier version of the BBC article, which prompted CAMERA’s complaint, and note some of the actual hardships faced by Iraqi Jews.

Refugee Revisionism

CAMERA’s critique of the article noted that, by focusing almost exclusively on one Jewish man’s glowing memories from his childhood in Iraq and ignoring anti-Jewish discriminatory laws and massacres, reporter Lipika Pelham effectively whitewashed the extreme hardships faced by Iraqi Jews.

Yakov Reuveni, the main subject of the story, was quoted describing easy coexistence with his Arab friends, with whom he celebrated Shia holidays, barbeques, and strolls along the riverbank. “We used to eat with them, sleep with them, go to school with them, the Arabs and the Jews went to the same high school,” he said.

The reporter concurred: “It was an easy, happy life.”

The main concern Jews in Iraq faced, it seemed, was food, a subject to which multiple paragraphs were devoted. The piece is dominated by discussions of “the fish called maskuf”; “arak, a strong aniseed flavoured local alcoholic drink”; “kubbeh, made with minced lamb”; “khitchri … a dish cooked with rice and lentils”; and “sweet pickled orange.”

In contrast to those detailed passages about food, the original article scarcely discussed the difficulties faced by Iraqi Jews — only three of about 30 paragraphs suggested things were not always so rosy for the ancient community. Those difficulties were eventually mentioned — vaguely and in passing — but only after the reporter first suggested the flight of Iraqi Jews to Israel was not due to adversity, but simply part of a “religious journey.” According to paragraph nine:

For the Jews of Middle Eastern origins, like their European co-religionists, coming to Israel was the culmination of a religious journey — it was the fulfilment of the centuries-old dream to live in the Promised Land.

Only much deeper in the piece, about 20 paragraphs in, did a quote by Reuveni and two sentences by the reporter finally provide a subtle hint that what drove the Jews from their homes might not have been a “centuries-old dream,” but rather something closer to a nightmare:

“We never thought of who was Jewish and who was Arab, until 1947. It all suddenly changed. The people that you knew as good people turned into bad people for you and you became bad for them. It was very sad.”

Anti-Jewish sentiment flared up after the creation of Israel and the subsequent Arab-Israeli war in 1948-49.

This led to the departure of most of Iraq’s ancient Jewish community. By 1952, 120,000 Jews had left Iraq for Israel.

The bizarre contradiction between these two motives for exile cited in the piece — in one paragraph the cause of emigration seems to be Jewish religious aspirations, and in another passage it is anti-Jewish sentiment that flared up after the creation of Israel — might be explained by the fact that the two paragraphs citing “anti-Jewish sentiment” which “led to the departure” were not part of the article as originally published, but were tacked on shortly after it was published.

In any case, other than the one quote in which Reuveni refers to friendly coexistence “suddenly” ending in 1947, and the passive phrase “anti-Jewish sentiment flared up,” Pelham ignored the hardships faced by Iraqi Jews. And she implicitly blamed these mysterious hardships — readers were left to guess what these might be — on “the creation of Israel” instead of on the Iraqis who persecuted their Jewish neighbors.

But it indeed was persecution, or worse, that brought to an end to the vibrant Jewish community in Iraq.

Carole Basri, an adjunct law professor at the University of Pennsylvania and representative of the World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries, describes the liquidation of the Jewish community in Iraq as ethnic cleansing:

… successive Iraqi government violated the human rights of Iraqi Jews. Over the years, these numerous violations added up to nothing less than the ethnic cleansing of this ancient Jewish community. (Carole Basri, The Jews of Iraq: a Forgotten Case of Ethnic Cleansing, 2003)

Iraqi independence in 1932 and the subsequent rise of Nazi influence in the country is widely regarded as a starting point for discussion of the modern history of Babylonian Jews. Maurice M. Roumani, director of the J.R. Elyachar Center for Studies in Sephardi Heritage at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, notes that

The Government of Iraq began to take specifically anti-Jewish steps practically from the moment of its independence; in 1934 the teaching of Hebrew was prohibited and students’ entry into high schools and universities restricted. Jews began to be dismissed from certain government positions. Physical attacks on Jews in Baghdad — including murders — became frequent from 1936 on; anti-Jewish propaganda was spread by an openly pro-Nazi and anti-Zionist regime. The tension and “shadowy persecution” erupted into violence in other cities too, where local Muslim leaders used the opportunity to extort money from the Jews. (Maurice M. Roumani, The Case of the Jews From Arab Countries: A Neglected Issue, 1983)

(Note that the BBC not only ignores the restrictions on Jewish entry into Iraqi schools, but in fact implies there were no such restrictions by quoting Reuveni’s assertion that “the Arabs and the Jews went to the same high school.” This quote is also misleading in light of the 6,000 Jews who attended the ten Alliance Israelite Universelle Jewish schools in Iraq. Ironically, one of the goals of that school system was “to provide effective support of those who suffer because they are Jewish.” Other Jewish schools existed alongside the Alliance Israelite Universelle, including the Midrash Talmud Torah and the Beit Zilkha yeshiva.)

In September and October 1936, Jews were murdered in Baghdad and Basra, and on Yom Kippur that year a bomb was thrown into a Baghdad synagogue.

In 1939, the Iraqi public school system began to follow a Nazi education model, complete with praise for Hitler and descriptions of Jews as an internal enemy. Sami Shawkat, the director general of the Iraqi Ministry of Education, wrote in his book These are Our Aims that the Jews, as an internal enemy, are more dangerous than the external enemies of the state, and should be treated as traitors.

|

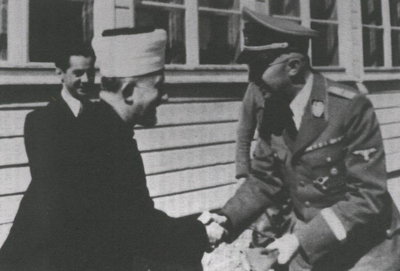

The situation worsened in 1941. A new Iraqi government, backed by Haj Amin al Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem best known for his collaboration with the German Nazi leadership and his role in anti-Jewish massacres in Palestine, forcefully took power in April of that year, and the Jews of Iraq immediately felt the impact.

British journalist Marina Benjamin described in a book about her family’s life in Baghdad the month that followed the coupe d’etat:

… the Jews were harassed by pro-Nazi elements mobilized by the rebel government. They had to contend with swastikas being crudely daubed all over the Jewish quarter and with direct intimidation by the Futuwwah [paramilitary youth organization], whose members brought rather too much enthusiasm to their new role of policing Baghdad. … the Jews served as punching bags ….

Hardly a day passed without some Jew or other being hauled up by the police and accused of signaling to British planes flying overhead. …

On May 6, 1941, a mob armed with knives and cudgels stormed the [Jewish] Meir Elias hospital looking for British agents who had reportedly based themselves there in order to signal to enemy bombers. The vigilantes attacked patients and staff, shooting indiscriminately. (Marina Benjamin, Last Days in Babylon: The History of a Family, the Story of a Nation, 2006)

Then, on the first two days of June, 1941, the Jews of Baghdad faced a devastating pogrom, known to Iraqis as the Farhoud.

Bat Ye’or, who writes about the treatment of minorities under Islamic rule, described the event as follows:

Iraqi soldiers, police and members of youth groups seized Jewish pedestrians, bound them hand and foot, and threw them under the wheels of tramcars; others were stabbed. Murder, pillage, rape, and the burning of Jewish shops and houses continued for two days … . (Bat Ye’or, Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide, 2002)

Marina Benjamin also described the “free-for-all slaughter”:

… trouble began in earnest when a number of Jewish men returning home that afternoon were accosted by a band of demobilized soldiers on the Khurr Bridge. The soldiers flew at them with fists and knives, kicking them to the ground and pummeling them with their boots in a frenzied release of pent-up frustration. Then they ran off, leaving one Jew dead and another sixteen injured. …

As dusk fell acts of pillage and murder spread, forcing the Jews, who had so recently come out of hiding, to run straight home and lock their doors. …

In Bataween [Baghdad’s main Jewish quarter], cries of horror and suffering could be heard throughout the night … women were raped, babies crushed, children mutilated. In this free-for-all slaughter, Jews old and young were killed. Some were shot and some stabbed. Houses big and small were broken into and plundered.

Indiscriminate looting of Jewish property, meanwhile, was urged with the slogan “Mal el Yehud halal,” or “Jewish property is kosher for the taking” (David Kazzaz, Mother of the Pound: Memoirs on the Life and History of the Iraqi Jews, 1999).

In two days, roughly 200 Jews were killed, 2,000 were wounded, and hundreds of homes and businesses were looted or burned.

The Farhoud, which devastated the confidence of the Iraqi Jewish community, might be described as the beginning of its end. Though the next six years would be relatively quiet, the stage was set for the eventual wholesale emigration/expulsion of Iraq’s Jews. Swastikas began “appearing everywhere.” An ominous 1942 British intelligence report noted that “the Iraqis will punish the Jews eventually” (Basri).

Indeed, the next phase of anti-Jewish hostilities — perhaps the pr edicted “punishment” — began in 1947, in the wake of the United Nations decision to partition Palestine. The Iraqi government quickly adopted what author and journalist Edwin Black described as “Nazi confiscatory techniques,” levying “exorbitant fines as punishment for trumped-up offenses.” Zionism was made a criminal offense. As Arab countries invaded the newly declared Jewish state, the Iraqi police ransacked Jewish homes and arrested hundreds of Jewish citizens (Edwin Black, “Dispossessed: How Iraq’s 2,600-year-old Jewish community was decimated in one decade,” Reform Judaism, Winter 2004). Hundreds more were dismissed from their public jobs. Crippling restrictions targeted Jewish commerce and travel. The government seized Jewish property, cut off municipal services to Jewish neighborhoods, and shut down Jewish newspapers (Basri).

The Jewish community’s sense of security was further eroded when Shafiq Adas, the richest Jew in Baghdad, was publicly hanged — amidst public rejoicing — after being convicted for allegedly selling scrap metal to Israel and having communist affiliations. His prominent Muslim attorneys were prevented from cross-examining prosecution witnesses and from calling their own witnesses. The British Ambassador to Iraq would shortly afterward draw parallels between the plight of Iraqi Jews and that of blacks in the American South, specifically citing the unjust court system in each locale as one of the similarities (Basri).

In response to these conditions, an increasing number of Jews emigrated illegally — legal emigration was not permitted — to Iran. Finally, in March 1950, the Iraqi government passed a law permitting Jews to leave the country, though at the cost of losing their Iraqi citizenship. A subsequent law froze the property of those who registered to leave.

Researcher Esther Meir-Glitzenstein noted that “what had begun as voluntary emigration turned into an expulsion.” Jews were reportedly threatened with murder, forced to hand over their property, and escorted from their homes by the police (Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, Zionism in an Arab Country: Jews in Iraq in the 1940s, 2004). Nuri Said, who became Prime Minister of Iraq in September 1950, was open about his desire to get rid of the country’s Jews:

The Jews have always been a source of evil and harm to Iraq. They are spies. They have sold their property in Iraq, they have no land among us that they can cultivate. How therefore can they live? What will they do if they stay in Iraq? No, no my friend, it is better for us to be rid of them as long as we are able to do so. (“Why Jews Fled the Arab Countries,” Middle East Quarterly, September 1995)

|

Eventually, about 120,000 people — almost the entire Jewish community — would escape the oppression, with little more than the clothes on their backs. Only 6,000 remained behind.

Such was the fate of the Iraqi Jews, whom the BBC described as having an “easy, happy life” and fulfilling a “centuries-old dream.”

In the introduction to his book The Case of the Jews from Arab Countries: A Neglected Issue, political scientist Maurice M. Roumani asserts that

Arab leaders pretend that idyllic relationships prevailed between Jews and Arabs in their countries preceding the advent of modern Zionism. However, they are fully aware that the reality was entirely different.

Judging by the pre-complaint version of the Pelham’s article, the same could be said about the BBC.

A Separate Standard for Palestinians

Only three weeks after the BBC published its whitewash of the plight of Iraqi Jews, it ran another piece about a displaced Middle East population. This one, “Obstacles to Peace: Refugees” by Martin Asser, was about Palestinian refugees.

The contrast between this piece and Pelham’s original piece is striking. Whereas the former spoke merely of the “departure” of Jews, who had “emigrated” from Iraq and “arrived” in Israel, the latter spared no expressive term to describe Palestinian refugees. They were “displaced,” “living in exile from homes and land their families had inhabited for generations,” “suffer[ing] the legacy of their dispossession” or even “ethnic cleansing” by “armed Jewish gangs” — and that only in the first six paragraphs.

While the first article ignored mainstream Jewish opinion about the plight of Iraqi Jews, the second embraced the Palestinian narrative as fact. Opinions that contrast with the Palestinian narrative were described, with seeming contempt, as “official Israeli history” or as coming from “Zionist historians.” Meanwhile, Asser accepted as accurate claims made by Badil, a Palestinian group that openly advocates the elimination of Israel as a Jewish state. Badil claims there are 1.5 million Palestinian refugees in addition to the 4.3 million who are registered with the United Nations, and Asser unquestioningly added these supposedly uncounted refugees to his total count of Palestinian refugees.

And while the first article avoided mentioning incontrovertible historical facts about the life of Jews in Iraq, for example the Farhoud and the expulsion of Jews, the second freely relayed refuted conspiracy theories about Israeli Prime Minister Ben Gurion’s supposed desire to “implement a covert plan to expel Palestinian civilians ….” (For a detailed rebuttal to this claim, see Efraim Karsh’s Fabricating Israeli History: The ‘New Historians.’)

But Asser did not stop at conveying dubious allegations by partisan sources. He himself condemns Israel with patently false accusations. For example, he claimed that “Israel has kept Palestinian refugees and their descendants out of negotiations on a settlement to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.” Whether he meant that Israel has kept the topic out of negotiations or kept actual refugees/descendants out of negotiations, Asser is wrong. Israeli and Palestinian negotiators did discuss the refugee issue at both the Camp David negotiations in 2000 and the Taba negotiations in 2001.

According to an EU “non-paper” written by former European Union Special Representative to the Middle East Process Ambassador Miguel Angel Moratinos:

Non-papers [about the refugees issue] were exchanged, which were regarded as a good basis for the talks. Both sides stated that the issue of the Palestinian refugees is central to the Israeli-Palestinian relations and that a comprehensive and just solution is essential to creating a lasting and morally scrupulous peace. Both sides agreed to adopt the principles and references with could facilitate the adoption of an agreement.

Both sides suggested, as a basis, that the parties shoul d agree that a just settlement of the refugee problem in accordance with the UN Security Council Resolution 242 must lead to the implementation of UN General Assembly Resolution 194.

The negotiators themselves concurred. A joint Israeli-Palestinian statement released on Jan. 27, 2001, just after the conclusion of the Taba Summit, noted:

The negotiation teams discussed four main themes: refugees, security, borders and Jerusalem, with a goal to reach a permanent agreement that will bring an end to the conflict between them and provide peace to both people. …

On all these issues there was substantial progress in the understanding of the other side’s positions and in some of them the two sides grew closer.

If, on the other hand, Asser meant to say that Israel has kept refugees themselves from sitting at the negotiating table, he is still wrong. The lead Palestinian negotiator on the refugee issue at Taba, Nabil Shaath, is himself a refugee from Safed (according to UNRWA’s unusual definition of a refugee). Others on the Palestinian negotiating team at Camp David and Taba are also refugees according to UNRWA.

The errors and distortions in the BBC’s two May 2007 articles about refugees are doubly cause for concern. First, because when viewed in isolation, each article betrays a disturbing bias that misleads readers. But the bias is most troubling when the articles are considered together. If both had shown a preference to their subjects’ narrative — that of Jewish and Palestinians refugees, respectively — this might suggest the BBC has a pro-refugee tilt that, even if problematic journalistically, is at least not motivated by institutional political leanings or by the nationality of the articles’ subject. But, it turns out, politics and nationality apparently are the driving force behind the BBC’s bias. In one article, the plight of the refugee was shamefully glossed over; in the other, it was exaggerated. In other words, both the article about Jews and the one about Arabs were skewed toward the Arab perspective at the expense of the Jewish/Israeli perspective.

Hopefully, the BBC’s willingness to amend its article about Iraqi Jews in Israel is a signal that the organization is trying to end its institutional bias. But for there to be real progress, the BBC must do more than just make changes to articles after they have been published. It must make sure editors and reporters understand that BBC’s Editorial Guidelines also apply to the Arab-Israeli conflict, and that advocacy for the Palestinian narrative and historical revisionism of Jewish suffering are unacceptable for a responsible news organization.