The basic history of the conflict was once widely understood. Jews returning to their historic homeland encountered opposition from Arabs, who claimed the entire land as their own. The British, who administered the disputed land on behalf of the League of Nations and United Nations, abdicated their authority. The United Nations then  proposed a two

proposed a two -state solution in 1947, comprising a Jewish state and an Arab state. The Jews accepted the compromise; the Arabs rejected it and attacked the newly declared Jewish state. The Jews prevailed and many Arabs living within the boundaries of the Jewish state fled to surrounding Arab states. These Arab states refused to assimilate and resettle them and the Palestinian Arab refugee problem was born.

-state solution in 1947, comprising a Jewish state and an Arab state. The Jews accepted the compromise; the Arabs rejected it and attacked the newly declared Jewish state. The Jews prevailed and many Arabs living within the boundaries of the Jewish state fled to surrounding Arab states. These Arab states refused to assimilate and resettle them and the Palestinian Arab refugee problem was born.

Among many academics, this basic history no longer suits contemporary ideological fashion. In its place, they have superimposed a European colonialist narrative onto the Arab-Israeli conflict. The colonialist narrative casts Jews as modern interlopers and discounts their nearly continuous presence in the land of Israel, despite periods of exile, through the millennia. The narrative also denies the central role of religious ideology and ethnic bigotry as the source of enduring Arab-Islamic enmity toward the Jewish state. It ignores or dismisses as irrelevant the torrent of hateful rhetoric directed at Jews in mosques, schools, bookstores, television, newspapers and from government officials. Instead, according to University of California professor James L. Gelvin “The problem is, simply put, a dispute over real estate.”1

Gelvin’s account, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, exemplifies the colonialist narrative. What he labels the “Zionist account”– that “the Zionists accepted the United Nations partition plan and were willing to live in peace with their neighbors; the Arab states rejected the partition plan and launched a war against the Jewish state” 2– is in his view a “misrepresentation” of the truth and not to be taken seriously. Instead, he depicts Zionism, the Jewish national movement, as a “prototypical” European nationalist movement usurping the land of indigenous inhabitants. Gelvin informs readers, “Other settler states, such as the United States, had been built on the ruins of indigenous societies, of course. But it was Israel’s misfortune that it did so under the harsh lights of the mid-twentieth century….”3

Defining the Arabs as Indigenous But Not the Jews

The colonialist narrative considers the religious and ethnic composition of the Palestine Mandate that existed just prior to the arrival in large numbers of diaspora Jews as the authentic state, which was overturned by Jewish immigration and the establishment of the Jewish state. From that basis, Gelvin frames the conflict as one between “the Jews and indigenous inhabitants of Palestine.”4

In so doing, he legitimizes the results of the Arab-Islamic conquests and subsequent suppression of pre-Islamic societies.5 The Arabs, who first arrived in large numbers as invaders in the 7th century C.E. and have been migrating in from surrounding lands ever since, are transformed into indigenous people, while the Jews, whose history on the land pre-dates the Arab conquests by nearly two thousand years and who did, in fact, maintain a presence in Jerusalem and other areas despite expulsions by conquerors, are denied such status. Bernard Lewis, Professor Emeritus of Middle Eastern History at Princeton University, explained the motive behind this,

The rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims. By depicting the great Arab Islamic expansion in the seventh century as a war of liberation rather than of conquest, the Arabs can free themselves of the charge of imperialism, the most heinous crime in the current political calendar. By establishing a direct link with the ancient inhabitants of their countries [who were mostly non-Arabs], they can … foster that sense of identity with the homeland through the ages.6

Gelvin’s granting of authenticity to the majority Arab population existing in early 20th century Mandatory Palestine obscures the fact that the population of Palestine has always been fluid, undergoing dramatic changes over the centuries. Under Byzantine rule, prior to Arab-Muslim invasion, the population was estimated at 3.5 to 4 million. Due to persistent neglect under Islamic rule, the population declined to about 300,000 in the 16th century and did not recover to its pre-Islamic level until after the establishment of modern Israel.7

Weighing what he considers Arab indigenous rights against ancient Jewish ties and the longing to return, Gelvin sides with the Arabs. He writes, “there is a big difference between remembering Jerusalem and undertaking the wholesale settlement activities in Palestine and eventually lodging a demand for Jewish self-determination in Palestine.”8 In other words, the Jews have over-reached. Gelvin clearly rejects the traditional view, grounded in a history that pre-dates the 20th century Arab identification as Palestinians, that the Jews are the indigenous inhabitants restoring their ancient nation-state.

Relying on Debunked Scholarship and Unsubstantiated Assertions

Drawing heavily upon the work of a group of controversial Israeli historians known as the “New Historians,” Gelvin’s recounting of events during the crucial years of 1947-1949 is undermined by his failure to recognize that the “New Historians” account has been largely debunked. University of London Professor Efraim Karsh exposed the “deliberate misrepresentation” of Israel’s founding history in two books, Fabricating Israeli History: The New Historians (published by Frank Cass, 1997) and Palestine Betrayed (published by Yale University Press, 2010). After carefully examining the original meeting notes of the Jewish Executive Agency (during the years 1938-1947), Karsh demonstrated that the “New Historians” constructed a false narrative depicting Jewish leaders as promoting the forced transfer of the Arab population. Gelvin ignores the work done by Karsh and others.

A second and related weakness in Gelvin’s book is his sparse and inconsistent use of footnotes. He makes numerous bold assertions and offers controversial interpretations of events without indicating the sources of his information or providing necessary context.

For example, he offers no source to back up his dubious claim that “an estimated 90% of the immigrants of the two aliyot [two large waves of Jewish immigration –aliyahs 2 and 3] left Palestine after only a brief sojourn there…”9

His charge that “the Israeli government took over approximately 94 percent of the property abandoned by Palestinians who fled and distributed it to Jewish Israelis”10 lacks context or a source. The context Gelvin omits is that over a million displaced Jews flooded into Israel from Europe and the surrounding Arab states creating a desperate need for housing. Gelvin does not ask if it is reasonable to expect the Israeli government to let abandoned property sit idle for years, decades, or longer, until the conflict is resolved. Gelvin also does not inform readers that in many cases the Arabs had a choice to make concerning the disposition of their abandoned property; they could have recognized the sovereignty of the state of Israel within its internationally recognized boundaries and agreed to pay taxes on the property to the new state.

Minimizing the Jewish Historical Connection

Feigning an even-handedness, Gelvin explains that “like the Zionist myth, the Palestinian national myth contains its own share of elisions and historically doubtful assertions.”11 But chapter after chapter, the book belies objectivity or balance. He injects, for example, that “Zionist historians of an earlier generation found comfort in the [Crusader] kingdom’s longevity,”12 voicing a theme favored by the Arabs linking Israel to the Crusaders. It does not reflect the mainstream Zionist view that sees the Jews as exiles permanently returning to rebuild their homeland.

While Gelvin discusses the Jewish historical “presence” in biblical times, the resilience of Jewish sovereignty in the states of Israel and Judea from the twelfth century B.C.E. until the second century C.E. and the continuity of an ongoing Jewish presence on the land is not clearly conveyed. 13 He writes: “Palestine was, after all, recalled in Jewish texts…” and refers to the “Jewish exile from Palestine…”14

But, in fact, Jews do not recall “Palestine” or lament exile from “Palestine.” They recall Israel and Judea — and Jerusalem.

The name “Palestine” is derived from the Philistines, a Greek people who inhabited the coast and fought against the Israelites. They disappeared after their conquest by the Babylonians in the seventh century B.C.E. The Romans later imposed the name “Palestine” after Jewish rebellion against Roman rule in 66 C.E. and 132 C.E. to erase the Jewish connection to the land. Arab adoption of the name Palestine is a 20th century phenomenon in response to Zionism.

The diminution of Jewish historical claims is further exemplified by Gelvin’s description of Hebron. He locates the ancient Jewish capital “in an area that most observers call, ‘the occupied West Bank’ but the Israelis officially designate ‘Judea and Samaria’ after the territory’s biblical names.”15 The implication is that Israel’s use of “Judea and Samaria” contravenes neutral world opinion. Gelvin does not explain that the term ‘West Bank’ is derived from Jordan’s illegal seizure of territory in the 1948-9 war to distinguish it from the east bank of the Jordan river where Jordan lies.

Gelvin also cherry-picks among archaeological accounts to cast doubt on Jewish national symbols. He labels the story of Masada a hoax, quoting a description of it, “[as] an elaborate and persuasive stage scenery for a modern passion play of national rebirth.”16 He portrays the Zealots as criminals and casts doubt on the “Jewishness” of the site. Erasing the Jewish past in the land and denying the extensive archaeological evidence of this past is a staple of contemporary Palestinian propaganda.

The Myth of a Flourishing Pre-Israel Arab Palestine

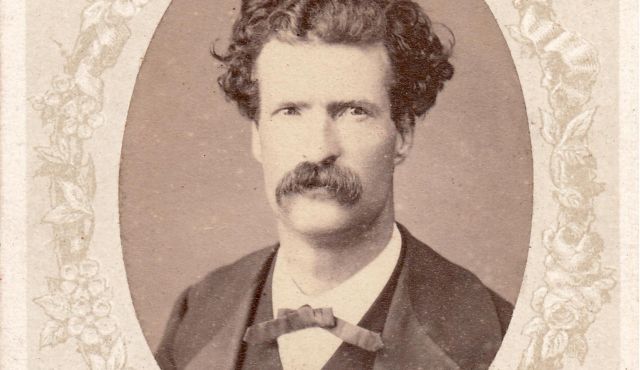

Gelvin paints a portrait of a flourishing pre-Israel Palestine overturned by Jewish settlers from Europe. In order to refute the observations of travelers to Palestine during the 19th and early 20th centuries, like the author Mark Twain, who found a desolate and abandoned land, Gelvin claims that “The forsaken state of these satellite villages created an impression of Palestine among Western visitors and Zionist settlers far removed from reality.”17 He dismisses Twain as uninformed and admonishes him and “early Zionists” for their failure to “comprehend that the seemingly abandoned and ramshackle villages on the [coastal] plain indicated an increase in security and prosperity, not an absence of habitation.”18 Gelvin exaggerates the extent of Arab development, obscuring the reality that much of the land had fallen into disrepair, its population reduced to warring clans.

Gelvin paints a portrait of a flourishing pre-Israel Palestine overturned by Jewish settlers from Europe. In order to refute the observations of travelers to Palestine during the 19th and early 20th centuries, like the author Mark Twain, who found a desolate and abandoned land, Gelvin claims that “The forsaken state of these satellite villages created an impression of Palestine among Western visitors and Zionist settlers far removed from reality.”17 He dismisses Twain as uninformed and admonishes him and “early Zionists” for their failure to “comprehend that the seemingly abandoned and ramshackle villages on the [coastal] plain indicated an increase in security and prosperity, not an absence of habitation.”18 Gelvin exaggerates the extent of Arab development, obscuring the reality that much of the land had fallen into disrepair, its population reduced to warring clans.

Nor is his portrayal of a flourishing Arab Palestine wrecked by Jewish usurpation supported by economic data. According to Karsh “In the two decades between the world wars, Arab owned citrus plantations grew sixfold, as did vegetable-growing land, while the number of olive groves quadrupled.”19 Historian Arieh Avneri’s analysis of extensive data demonstrates that Arab economic growth in the Palestine Mandate coincided with Jewish economic development.20

Economic growth resulting from Jewish settlement spurred Arab migration into the Mandate. Many Arabs residing in the Palestine Mandate in 1947 were recent arrivals, lured by employment opportunities in the expanding Jewish economy that needed laborers. Fred Gottheil, Joan Peters and Karsh document how Arab population growth concentrated near Jewish areas of settlement. Gottheil contrasts increasing Arab numbers around Jewish-settled areas with the concurrent outflow of population occurring in adjacent states like Syria.21 Karsh quotes the British Peel commission’s statement in 1937 that “the general beneficent effect of Jewish immigration on Arab welfare is illustrated by the fact that the Arab increase in population is most marked in the urban areas affected by Jewish development.”22 Gelvin ignores the detailed analyses produced by these authors.

Inverting Aggressors and those Attacked

Significant gaps in Gelvin’s account appear in his handling of the animosity between Arabs and Jews. His failure to adequately disclose the role played by Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, in inciting violence and hardening Arab attitudes toward the Jews is symptomatic of his general avoidance of the religious and ideological component of Arab rejection of Israel.

Gelvin shifts responsibility for initiating violent outbreaks onto the Jews as demonstrated in his description of the riots in 1929:

In August 1929, for example, rioting broke out in Jerusalem. Rumors that each community was attempting to restrict the other community’s acc

ess to its holy sites inflamed tensions, and a demonstration organized by Betar demanding Jewish control over the Western wall – a site that abutted the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif – seemed to prove the worst to the Muslims.23

While conceding that the Mufti was not blameless, Gelvin lets him off easy, stating, “Nevertheless, neither [the Mufti or the Jews] was directly responsible for the outbreaks.” 24

In contrast, authors Joseph Shechtman (The Mufti and the Fuehrer, published by Thomas Yoseloff, 1965) and Jennie Lebel (The Mufti of Jerusalem: Haj-Amin el-Husseini and National-Socialism, published by Cigoja Stampa, Belgrade, Serbia, 2007) 25 describe the Mufti’s central role in triggering the violence by spreading the false charge that Jews intended to demolish the Al Aqsa mosque. In a case of unintended irony, Gelvin compares the 1929 riots to Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount in September 2000 that marked the outbreak of the Second Intifada. Gelvin dismisses the claim that Palestinian leader Yassir Arafat intentionally provoked the unrest, even though several of Arafat’s confidants have made clear the Palestinian leader launched the violence, using Sharon’s visit as a pretext.26

Similarly, Gelvin traces the outbreak of the Arab revolt in 1936 to what he alleges were Jewish preparations for war. He writes,

At the end of 1935, British officials in Jaffa uncovered a large shipment of arms and ammunition destined for the Zionist community. For many Palestinians, this could only mean one thing: The Zionist community was arming itself and preparing for war.27

In fact, Karsh and others trace the outbreak of the revolt to April 1936 to the murder of 9 Jews in Jaffa. But Gelvin misses the mark in a more fundamental way. The Arab revolt was as much about an internecine struggle for power between different Arab factions as it was about Jewish immigration or British control. Karsh tallies 1,112 Arabs murdered in inter-Arab violence as opposed to 429 Jews and 151 British soldiers.28 Through the murder and intimidation of his opponents, by the late 1930s al-Husseini had consolidated his preeminence in Palestinian Arab politics.

The Mufti invoked religious supremacism along with pseudo-scientific and conspiratorial anti-Semitic themes popular in Europe. The religious-ideological component is crucial to understanding the transformation of the Arab-Israeli conflict in the 1930s. But because he ignores the ideological dimension of Arab rejection of Israel, Gelvin can offer only limited insight into the inter-Arab political struggle that culminated in the adoption of the most extreme positions.

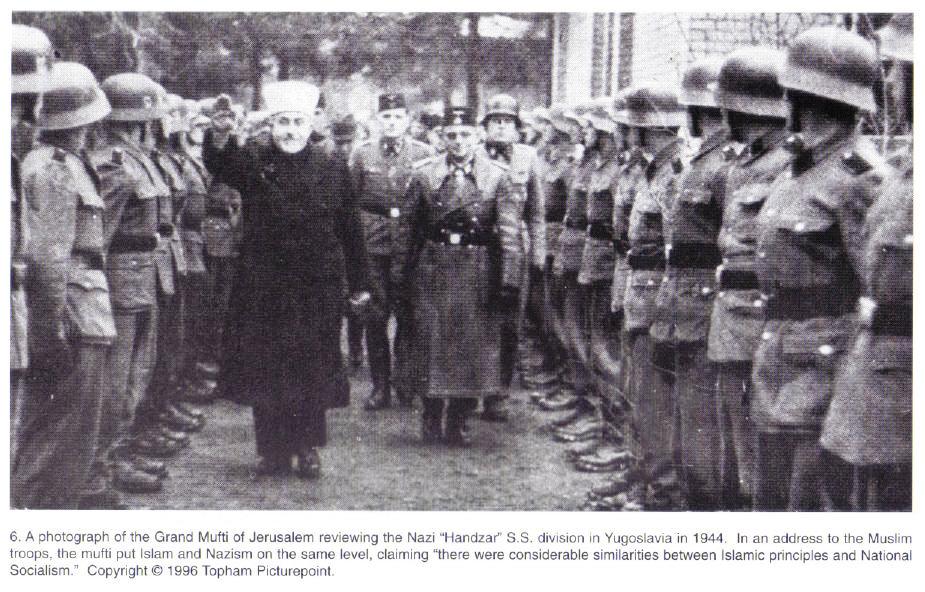

Glossing Over Haj Amin al-Husseini’s Collaboration With the Nazis

The relationship between the Mufti and the Nazis has generated renewed interest, especially among German historians. But to Gelvin, this component of Palestinian Arab history is unimportant. All he can muster is

The Hajj Amin’s opportunistic wartime residence and propaganda activities in Nazi Germany certainly was not the proudest moment in the history of Palestinian nationalism. And, certainly, opponents of Palestinian nationalism have made good use of those activities to associate the Palestinian national movement with European-style anti-Semitism and the genocidal program of the Nazis.29

Contrary to Gelvin’s assertion, it was not just the opponents of Palestinian nationalism who associated the Mufti with the Nazi program; the Allies classified the Mufti as a major war criminal and intended to try him at Nuremberg before his ‘escape’ from French confinement.

Serbian author Jennie Lebel documented the assistance the Mufti provided to the Nazis in their terror campaign in the Balkans. He helped recruit two Muslim SS divisions, including the notorious Handzar division, which committed atrocities against Serbs.30 The Mufti lobbied the Germans to expand the scope of their killing operations to the Jews in the Middle East. It is easy to understand why Gelvin does not delve into the Mufti’s collusion with the Nazis; full disclosure would raise considerable doubts over his assertion that the confict is just about real estate.

Emphasizing Jewish Terrorism and Ignoring Arab Terrorism

While downplaying Arab extremism and terrorism, Gelvin emphasizes examples of Jewish extremism and violence.

He portrays the group the British authorities called the Stern Gang (their Hebrew acronym was LEHI, “Fighters for the Freedom of Israel”) as eager to make a deal with Hitler. Gelvin writes, “The Stern Gang sought to persuade Hitler’s government that sending Jews to Palestine would accomplish the Fuhrer’s goals of rendering Europe judenrein.”31 Shorn from the context of the on-going slaughter occuring in Europe and the desperate schemes concocted by Jewish groups of varied political persuasions to rescue Jews, his insertion of this topic amounts to cruel taunting.

More telling, he omits mention of the Mufti’s intercession with Nazi authorities to cancel a deal that would have rescued more than a thousand Jewish children. Instead the children were sent to the death camps.32 The actions of the British during the war blocking legal Jewish entry to Palestine also merits less attention than is warranted. Gelvin simply sums it up that “wartime conditions permitted only 82,000 Jews to emigrate to Palestine during World War II.” 33

Misrepresenting the Events of 1947-1949

In his handling of the crucial years of 1947-1949, Gelvin continues to adhere to the Palestinian and the “New Historians” narrative. Concerning the latter, Karsh observed:

… Rarely mentioned in the revisionist accounts are the Arabs’ outspoken commitment to the destruction of the Jewish national cause…the sustained and repeated Arab efforts to achieve that end from the early 1920s onward; and the no less sustained efforts of the Jews at peaceful coexistence. Zionism emerges, instead, as a colonizing and expansionist ideology and movement, an offshoot of European imperialism at its most rapacious.34

Most prominent of the “New Historians” is Benny Morris – although in recent years, Morris has backed away from the perspective he was instrumental in creating. Gelvin frequently cites Morris’ work along with more doctrinai

re anti-Zionist revisionists like Avi Shlaim and Ze’ev Sternhell. Karsh and his refutation of the “New Historians” are missing.

The “New Historians” portray Jewish leaders of pre-state Israel, especially David Ben Gurion, as scheming to expel the Arabs.35 Gelvin includes partial quotes by Ben Gurion taken out of context, such as, “Now a transfer of wholly different dimensions will have to be carried out.” He engages in a deceptive reading of what Morris wrote in order to pronounce that “during the 1948 war, Ben Gurion put his recommendations into practice in a campaign known as ‘Operation Hiram’ [where] a wholesale transfer of population took place in the Galilee region.”36

It is instructive to look at what Morris actually wrote about Israeli leaders’ attitude toward Palestinian flight during Operation Hiram:

This attitude was not converted into or embodied in formal government agreement or even IDF General Staff policy. Neither before, during nor immediately after Yoav and Hiram did the Cabinet or any of its committees decide or instruct the IDF to drive out the Arab population from the areas it was about to conquer or had conquered. Nor as far as the available evidence shows, did the head of the defence establishment – Ben-Gurion, IDF CGS Dori or Yadin – issue any general orders to the advancing brigades to expel or otherwise harm the civilian populations.37

Misrepresenting Ben-Gurion’s position on the Palestinian population is a cottage industry among anti-Zionist historians. In Fabricating Israeli History, Karsh shows how the “New Historians” used fragmentary quotes and manipulated passages to create the misleading impression that Ben Gurion favored forcible removal of Palestinian Arabs from the land. 38 When viewed in their full context, Ben Gurion’s statements reveal the opposite meaning, showing that he opposed the forced removal of Arabs from the land. For example, Karsh cites a statement by Ben Gurion that “If the Arab citizen will feel at home in our state… then Arab distrust will subside and a bridge can be built to a Semitic, Jewish-Arab alliance.”39, 40

Gelvin recites the standard fare of massacre allegations against Israel. He includes a quote alleging that the Arabs killed at Deir Yassin were “mostly women and children. Many, many people were massacred at that village”41 He offers no hint that details of the oft-repeated account are disputed. For instance, an Arab survivor, Ayish Zeidan, told the Daily Telegraph [U.K]. in 1998,

The Arab radio talked of women being killed and raped, but this is not true… I believe that most of those who were killed were among the fighters and the women and children who helped the fighters. The Arab leaders committed a big mistake. By exaggerating the atrocities they thought they would encourage people to fight back harder. Instead they created panic and people ran away.42

In his handling of the Arab flight, Gelvin declines to spar with distinguished scholars who dispute his perspective. Instead, he uses the late novelist Leon Uris as a foil, ridiculing his depiction of Palestinian flight as an “old canard about Arab leaders urging the Palestinians to get out of the way of incoming [Arab] tanks.”43 He mentions but quickly dismisses as irrelevant the orders issued by the Arab Higher Committee for Arab civilians to flee and asserts that no records indicate any “Arab nation directed the Palestinians to leave.” 44

In fact, former Syrian Foreign Minister Haled al Azm confessed in his memoirs, “Since 1948, we have been demanding the return of the refugees to their homes. But we ourselves are the ones who encouraged them to leave. Only a few months separated our call to them to leave and our appeal to the United Nations to resolve on their return.”45 Former Palestinian Arab officials as well have lamented the Arab flight as a mistake. Karsh provides extensive details about Palestinian flight, summing it up as “a self inflicted catastrophe.”46

Gelvin repeats the face-saving excuse given by the Arabs for their military defeat, claiming that the Jews fielded a larger army. In reality, the mobilization of a substantial portion of the Jewish population does not directly compare to the professional armies fielded by the Arab states that were drawn from a far larger population base. Nor does it account for the overwhelming advantage these Arab armies possessed in artillery, tanks and aircraft.

He picks up on another favorite theme of the “New Historians,”– one promoted especially by Avi Shlaim – that “the Jordanians displayed closer coordination with the Zionists than with other Arab states.”47 In Fabricating Israeli History Karsh debunks the charge of collusion between the Jordanians and the Israelis showing that conversations between Jewish leaders and Jordanian officials failed to alter events. 48

Gelvin depicts the Suez war of 1956 and the Six-Day War of 1967 as the fallout of an alleged Israeli scheme to blow up American and British installations and an Israeli military operation against Arab terrorists in Gaza. He writes, “The Israeli raid triggered a chain of events that led first to the Suez war of 1956, and then to the 1967 war.” 49 This is a spurious emphasis on tangential incidents that ignores the obvious direct causes: Egypt’s imposition of a naval blockade, ordering the UN peacekeepers out of the Sinai and positioning of a large military force there. ( Current Israeli ambassador and noted historian Michael Oren has written a comprehensive account of the Six-Day War.)

Misrepresenting U.N. Security Council Resolution 242

Gelvin mischaracterizes elements of American policy and the principle United Nations resolutions. In discussing U.N. Security Council Resolution 242 he writes “The Israelis like to point out that the resolution nowhere states that they must withdraw from all the occupied territories.”50 But, it is not simply the Israelis who point this out; the authors of the U.N. resolution, Eugene Rostow, Hugh Foote (Lord Caradon), George Brown and Arthur Goldberg each explained that the resolution was intentionally worded to not require Israel to withdraw from all of the territories because they believed Israel had claim to some of the territory and they felt that it was ill-advised for Israel to return to the pre-1967 armistice lines. 51

Gelvin offers a dubious interpretation of the so-called “three no’s – no negotiations, no peace, no recognition” voiced by the Arabs after the 1967 war, claiming that the Arab position reflected a “subtle tactical shift” toward accomodation and not the self-evident rejection of peace with Israel. 52 His interpretation is contradicted by the inflexible terminology used by the Arabs and is inconsistent with their continued use of eliminationist rhetoric and subsequent acts of aggre

ssion against Israel.

Biased Recounting of More Recent Events

In the chapters of the book dealing with more recent events, omissions and bias are increasingly evident. Gelvin ignores the rampant anti-Jewish rhetoric of the Palestinian Authority and Hamas. In eight pages of discussion of Hamas he fails to mention the passages in the Islamist organization’s charter alleging a worldwide Jewish conspiracy responsible for both World Wars or the unambiguous exhortation to kill Jews (see the last paragraph of Article 7 of the Hamas Charter). He is also silent about the Palestinian Authority’s adulation of terrorists and habit of naming street squares, summer camps and girl-scout troops after terrorists who murdered Israeli civilians. In fact, Palestinian Arab terrorism is a topic about which Gelvin has little to say.

He describes the cross-border attack by Hezbollah into Israeli in 2006 as a “daring raid” and later commends the terrorist militia for its “savvy resistance.” 53 His choice of words describing Hezbollah terrorism is noticeably more adulatory than how he describes the violent activities of Jewish militants in pre-state Palestine.

Gelvin writes of Israel’s “assassination policy against Palestinian leaders” 54 without clarifying that Israel targets senior figures involved in planning and instigating terrorist acts, but avoids targeting Palestinian political leaders not intimately involved in terrorism.

Gelvin repeats a U.N. envoy’s charge that the destruction of portions of Jenin were “horrific beyond belief” but fails to add that the inflammatory charge – that soldiers had carried out a massacre – was refuted by a U.N. investigation which found that of the 52 Palestinians who died in the Israeli incursion, at least half [and as many as 46] were combatants. The area of destruction in Jenin was confined to a city block and 23 Israeli soldiers died (by far the highest casualty toll of any Israeli incursion into a Palestinian town) precisely because the Israelis decided not to bombard the area in order to avoid civilian casualties.

Recommending Biased Sources

At the conclusion of each chapter, Gelvin includes a list of sources under “Suggestions for further readings.” Many of the authors he recommends are strident, anti-Israel polemicists. Students are not directed to the works of distinguished historians like Michael Curtis, Arieh Avneri and Efraim Karsh whose archival research has illuminated the founding of the modern state of Israel and the response of the Palestinian Arabs.

Conclusion

Gelvin describes his book as interpretive history implying that this relieves him of the responsibility for presenting a complete and balanced historical account. But even interpretive history must be factually accurate and provide credible sources for controversial contentions. It is incumbent upon serious scholars to acknowledge and debate with other scholars who disagree with the author’s positions. His failure to acknowledge those works that refute the “New Historians” reflects negatively on his diligence. Gelvin’s book will undoubtedly find its way to many classrooms unaccompanied by any objective account. The colonialist narrative that he champions is a misrepresentation of the historical record and falls apart under serious scrutiny. Instructors should be aware before assigning such a work that other historical accounts would far better serve students seeking a full, factual and scholarly portrayal of events.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Appendix 1 lists additional factual errors, misrepresentations and omissions from Gelvin’s book:

• Page 1: “Yishuv had incorporated close to 80 percent of Palestine…”

Gelvin references the original Mandate that included Transjordan, but in several places in the book he emphasizes the above statement as valid. In fact, Israel incorporates 23 percent of the Palestine Mandate defined in the Balfour Declaration.

• Page 4: He describes the Gaza Strip as ” estimated to be the most densely populated territory on earth.”

There are numerous territories of similar size more densely populated than the Gaza Strip, including the autonomous state of Singapore. Furthermore, many cities encompassing similar land area have denser populations than the Gaza Strip, including portions of Israel’s coastal strip.

• Page 72: He writes, “The Irgun perpetrated some of the most appalling atrocities committed in modern Palestine, including a campaign of “reprisal” bombings in Arab markets, (during which close to 80 Arabs were killed) and the wholesale massacre of an estimated 100 to 250 innocents in the village of Deir Yassin in 1948.”

Gelvin provides no evidence to backup his assertion of an organized campaign.

• Page 123: He writes, “Future prime minister of Israel Menachem Begin executed the attack” on the King David Hotel.

Gelvin leaves out important details. The target was not a civilian one, but rather the site of the British military command and criminal investigation division. The bombers issued three warnings to enable evacuation — to the hotel, to the French Consulate and to the Palestine Post. Years later, the British admitted that a warning call was received but ignored.

• Pages 124-126: Gelvin’s lengthy discussion of UN resolution for partition of Palestine fails to clarify the salient fact that the Arabs too were offered a state and rejected it.

• Page 173: Concerning the Egyptian blockade of the straits of Tiran in 1967, he writes “For Israel, the closing of the strait was an act of war.”

This is not an Israeli interpretation, it is accepted in international law.

• Page 185: Gelvin presents the economic transformation of the West Bank and Gaza as only benefitting Israel. He claims these territories served as a “captive market” for Israeli goods, flooding Palestinian markets with Israeli agriculture, while driving Palestinians into unskilled labor away from agriculture.

This characterization distorts reality. Economic data from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank all demonstrate significant increases in GNP and per capita income, along with dramatic improvements in living standards, in both the West Bank and Gaza from 1967 onward.

• Page 185: He writes that “Currently, Israel derives almost 40 percent of its water from aquifers it shares with the West Bank and about 25 percent from aquifers located exclusively in the West Bank.”

This is a frequently repeated canard that misrepresents reality. Israel has primary water rights in the aquifers due to their location and shares water with the West Bank beyond the requirements of Israeli-Palestinian agreements.

• Page 192: He writes, “the Israeli government acquires the land for settlements through expulsions and selective enforcement of the late 1858 Ottoman land code…”

In fact, Israeli settlements on land captured in 1967 have not been obtained by expelling the Arab population. Settlements have been built almost entirely on uninhabited state land.

• Page 193: He writes, “Before the Reagan administration, the United States government also called Israel’s settlement policy illegal.” He then describes President George W. Bush’s letter to Ariel Sharon which contained acceptance of some changes on the ground as a “reversal of America’s position.”

In fact, the American position has been that the settlements were legal. Only briefly during the Carter administration were settlements deemed illegal. Reagan restored the pre-Carter American position.

• Page 193: Gelvin claims that that the Bush administration for the first time described the Israeli position that the territories are “disputed.”

That is also false as demonstrated in the wording of UN Security Council Resolution 242, along with the League of Nations Palestine Mandate, Article 6 which is incorporated in the U.N. Charter Article 80.

• Page 221: Gelvin writes that Palestinian suicide bombers “target both Israeli soldiers in the territories and civilians in Israel.”

A review of suicide bombings demonstrates uniform targeting of civilians

• Page 253: He describes an Israeli artillery barrage that killed eight Palestinian members of a familly on a Gaza beach in 2006. A subsequent investigation determined that Hamas ordinance was the likely cause of the explosion.

1 James L. Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, Cambridge University Press, 2005, 2007 reprinted 2008, 2010, p.3

2 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 128

3 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 127

4 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 14

5Efraim Karsh, Islamic imperialism – A History, Yale University Press, 2006

6 Bernard Lewis, Semites and Anti-Semites, W.H. Norton and Co.,1986, p. 48

7Michael Curtis, Joseph Neyer, Chaim Waxman, Allen Pollack, editors, Transactions Books, 1975, The Palestinians – People, History, Politics p. 11

8 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 10

9 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 71

10 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 166

11 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 12

12 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 4

13 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 6-7

14 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 7

15 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 9

16 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 10

17 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 30

18 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 30

19 Efraim Karsh, Palestine Betrayed, Yale University Press, 2010, p. 13

20 Arieh L. Avneri, The Claim of Dispossession – Jewish Land-Settlement and the Arabs 1878-1948, Transaction Books, 1984

21 Fred M. Gottheil, Arab Immigration into Pre-state Israel: 1922-1931, p. 30-39 in The Palestinians – People, History, Politics

22 Karsh, Palestine Betrayed, p. 12

23 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 94

24 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 94

25 Jennie Lebel, The Mufti of Jerusalem: Haj-Amin el-Husseini and National-Socialism

26 See for example the statements by Marwan Barghouti: “The explosion would have happened anyway. It was necessary in order to protect Palestinian rights. But Sharon provided a good excuse. He is a hated man.” New Yorker, January 29, 2001)

27 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 102

28 Karsh, Palestine Betrayed, p. 35

29 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 119

30 Lebel, The Mufti of Jerusalem: Haj-Amin el-Husseini and National-Socialism. The author, a Serbian historian, writes extensively about the Mufti’s involvement in raising Muslim SS divisions.

31Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 120

32Lebel, The Mufti of Jerusalem: Haj-Amin el-Husseini and National-Socialism

33Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 120

34 Karsh, Palestine Betrayed, p. 4

35 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 137

36 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 137

37 Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 464

38 Karsh, Fabricating Israeli History – The ‘New Historians’ Frank Cass & Co., pages 37-63

39 Karsh, Fabricating Israeli History – The ‘New Historians’, p. 22 and p. 24

40 Karsh, Fabricating Israeli History – The ‘New Historians’, p. 24

41 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 138

42Daily Telegraph, April 8, 1998

43 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 131

44 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 136

45 The Memoirs of Haled al Azm, p. 386-7

46Karsh, Palestine Betrayed, see pages 230-243.

47 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 171

48 Karsh, Fabricating Israeli History, see pages 69-107.

49 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 171

50 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 179

51 Eugene Rostow, The New Republic, “Resolved: are the settlements legal? Israeli West Bank policies,” Oct. 21, 1991 and see Hugh Foote (Lord Caradon), Journal of Palestine Studies, “An Interview with Lord Caradon,” Spring – Summer 1976, pgs 144-45:

52 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 180

53 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 252

54 Gelvin, The Israel-Palestine Conflict – One Hundred Years of War, p. 253