When German Bishop Gregor Maria Franz Hanke made a direct comparison between the West Bank City of Ramallah and the Warsaw Ghetto during his recent trip to Israel, he did more than exhibit a tremendous ignorance of history and of the current situation in Israel. He also adopted rhetoric used by Arab anti-Zionists seeking to portray Israel as a legitimate target of contempt and made a comparison which is described as anti-Semitic by a draft document issued by the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia.

The bishop made the comparison during a recent visit to Israel organized by the German Bishops’ Conference to the Holy Land on Friday, March 2, 2007. Haaretz reported on Tuesday, March 6, 2007 that between a visit to Yad Vashem (the Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem) and Ramallah, a city in the West Bank, Hanke said “This morning we saw pictures of the Warsaw ghetto at Yad Vashem and this evening we are going to the Ramallah ghetto.”

Previously, German Cardinal Joachim Meisner compared the security barrier built to stop terror attacks from the West Bank to the Berlin Wall and asserted that “something like this is done to animals, not to human beings.”

The outrageous comparison between Israeli efforts to prevent terror attacks and Nazi efforts to wipe out European Jewry is demonstrably false. Ramallah is not in any, way shape, or form comparable to the Warsaw Ghetto.

The Warsaw Ghetto was created by the Nazis as a means of collecting Jews in preparation for their extermination, first by starvation and periodic shootings, later by mass transport to killing centers.

Details from Yad Vashem’s website provide some background about conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto:

Following the German occupation of Warsaw in September 1939, the city’s 375,000 Jews were subjected to forced labor, brutal attacks, strict anti-Jewish legislation, and the confiscation of their property. In October 1940, a ghetto was planned in the Jewish quarter in northern Warsaw, and on 16 November it was sealed off. Along with Warsaw’s Jews, Jews from smaller outlying communities were moved to the ghetto, which swelled to 445,000 residents. Conditions within were dire, and malnutrition, overcrowding, and disease were rampant; one out of five inhabitants perished within the ghetto walls. Nonetheless, residents participated in educational and cultural activities.

Following months of night raids and random killings in early 1942, the first wave of deportations began in July 1942. By 12 September, about 300,000 Jews had been deported from the ghetto—some 254,000 to the Treblinka extermination camp.

Initial attempts to create a comprehensive Jewish underground in the ghetto had faltered. However, after the end of the mass deportation, the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB) was formed: a conglomerate of all the political youth organizations in the ghetto, with the exception of the Revisionists (Beitar movement), who created their own fighting organization called the Jewish Military Union (ZZW).

Deportations from the Warsaw ghetto recommenced on 18 January 1943. Under the leadership of Mordecai Anielewicz, the ZOB launched its first display of hand-to-hand armed combat against the Germans in the ghetto streets. After four days the deportations stopped, which the Jews construed as a sign of German weakness inflicted by use of armed force.

Following the German “retreat,” the ZOB began to prepare for the final, full-scale uprising against the Germans. Twenty-two units were formed, each one representing a different youth movement. The ZOB comprised 500 fighters, while the ZZW had 200-250 fighters.

On 19 April 1943, the final liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto began. As the general population hid in underground bunkers, the fighters attacked, launching the Warsaw ghetto uprising—the first large-scale uprising of an urban population in occupied Europe. Days of guerilla-type warfare ensued, catching the Germans off guard and ill-prepared. After three days, the Germans changed tactics, torching the ghetto, building by building. They forced the fighters out of hiding by hurling grenades into the bunkers or pumping in tear gas. Several of those who emerged from their hideouts were murdered on the spot.

By the time the uprising came to an end in mid-May 1943, only a few hundred inhabitants of the Warsaw Ghetto were able to escape the city alive.

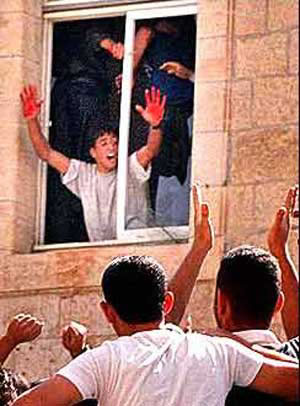

|  |

The total number of Palestinians in all of the West Bank and Gaza killed in the past six years totals approximately 4,400 people, many of them armed combatants.

Any civilian deaths are a tragedy. But casualties in Ramallah and across the West Bank are obviously not the result of a genocidal campaign intended to wipe the Palestinians from the face of the earth. There is no forced labor in Ramallah; no armbands; no starvation. The city has seen poverty, but no more than in many cities in developing economies. There are no deportations to extermination camps. No decree prevents Palestinians from running bakeries, owning radios and telephones, dealing in textiles or purchasing books.

Also disturbing is that the bishops’ statements mirror rhetoric from virulent anti-Zionist organizations that routinely compare Israel to the Nazi regime. For example, at the notorious UN racisim conference that took place in Durban, South Africa in September 2001, the Arab Lawyers Union distributed a book with a cover that superimposed the Star of David over the Nazi Swastika. While it might not have been a surprise for the Union to distribute such materials—the ALU supports Hezbollah, routinely calls for anti-Israel “resistance,” and its Deputy Secretary-G eneral Abd-al-Azim al-Mughrabi has explained that the “[s]truggle against the Israeli enemy is a struggle of existence, not of boundaries”—it is shocking that the German bishops adopted their rhetoric.

Fortunately, there is evidence that the Catholic community in Germany is distancing itself from the comments of the Bishops. According to Spiegel:

The Catholic Church in Germany is now trying to diffuse the row with a number of apologies. Hans Langendörfer, the Secretary General of the German Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said he regretted the remarks made by the bishops. They were made during the visit to Bethlehem “under the pressure of a demanding situation,” and were by “emotionally affected individuals who made a few very personal remarks, which have already been self-critically corrected.” He added, “That is especially true of a passing remark that referred to the Warsaw Ghetto.”