Coverage of state funerals often simulates gossip at a cocktail party, where the status of the deceased is measured by the wattage of the celebrities in attendance. Often overlooked is the deliberately calibrated message a nation sends as it follows the established diplomatic protocols for representation. This process takes on increased significance for the funeral of a controversial figure. Such events provide a rare moment of clarity, revealing bonds that exist between nations and reinforcing a sense of shared history.

Ariel Sharon was one such controversial figure, a patriot and hero to most Israelis, scorned by his detractors and detested by Israel’s enemies. His funeral did not draw the vast international retinue who attended the funeral of Yitzhak Rabin, another former Israeli military hero, who subsequently became Prime Minister. Rabin’s funeral drew luminaries from far and wide in recognition of the internationally lauded steps he had taken to resolve the conflict with the Palestinians and because he paid with his life. In contrast, while Sharon’s strong leadership looms large in the survival of modern Israel, he was widely seen as a polarizing figure.

Respected for his decisiveness, tactical brilliance and personal courage, Sharon was nevertheless held in contempt by many denizens of the international community, who portrayed him as a misbehaving brute with blood-stained hands. He symbolized a self-reliant, arrogant Israel that defied international consensus over concessions the Jewish state needed to make to achieve peace.

Of the 20 nations that did send representation to his funeral, most sent lower level diplomats. A few nations, however, risked international reproach by sending high level representation.

The nations that provided high level representation were:

• The Federal Republic of Germany: represented by the Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs, Frank-Walter Steinmeier

• The Republic of Romania: represented by the Vice Prime Minister, Liviu Dragnea

As Israel’s closest ally, high level representation from the United States, was not surprising, although it was less visible than expected, an indication of ambivalent feelings toward Sharon among American officials.

The strong British representation delivered a rebuff to elements of the British media and Foreign Office, who chastise the Jewish state for its policies concerning the Palestinians. To an influential segment of the British elite, Ariel Sharon was a uniquely detestable figure who incited vicious caricatures in the British media.

There was an unspoken poignancy to Australia’s representation. Sharon’s status as one of Israel’s most celebrated and daring military commanders recalls the service of John Monash, Australia’s most distinguished military commander and an independent thinker, who was also a Zionist and a Jew.

Germany’s representation was appreciated and expected. It requires little discussion due to the unique historical circumstances.

Czech Republic and Israel: A Shared Tragedy of Betrayal

Czech history has parallels to Israel’s and is intimately entwined with it. Like Israel, Czechoslovakia was born out of the turmoil of war. Created after World War I, when the concept of self-determination was seen as the panacea to war, Czechoslovakia’s multi-ethnic patchwork thwarted efforts to draw well-demarcated borders to separate the different ethnic groups. The Czechoslovakian state found itself saddled with a large German minority [Sudetenland] who viewed the creation of the state as a historical mistake that had to be reversed. The Sudeten Germans clung to a pan-German vision and agitated for the restoration of the German state in the territory they shared with Czechs.

The tragic history of the betrayal of Czechoslovakia and appeasement of Hitler is well known. Europe’s principle democracies, Britain and France, abandoned the fledgling democracy at the Munich Conference in 1938, giving in to the bullying of Adolf Hitler.

Believing that resistance to a resurgent Germany was futile, Czech leaders despaired and acquiesced to the dismantling of their state. The failure to resist Nazi coercion and the catastrophe that ensued presented an historic lesson to the Jewish leadership in Palestine nine years later as they confronted Arab threats of annihilation and abandonment by the mandatory British authority. The sellout at Munich taught that it was a mistake to trust the promises of diplomats or leave ones fate in the hands of foreign leaders.

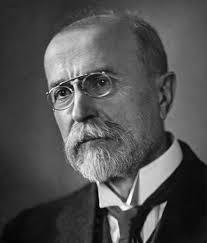

Less known is the strong sympathy Czechoslovakia’s founders and leaders had for Zionism. Tomas Masaryk, the principal figure of Czechoslovakian independence and the state’s first President, had deep sympathy for Zionism, writing in 1918:

“As regards Zionism, I can only express my sympathy with it and with the national movement of the Jewish people in general, since it is of great moral significance. I have observed the Zionist and national movement of the Jews in Europe and in our own country and have come to understand it is not a movement of political chauvinism, but one striving for the moral rebirth of a people.” 1

Masaryk saw similarities between Czech national aspirations and those of the Jews.

Masaryk saw similarities between Czech national aspirations and those of the Jews.

During World War II, the leaders of the Czech government in exile in London, Eduard Benes and Jan Masaryk, Tomas Masaryk’s son, were both friends of the Jewish community and su

pportive of Zionism.

Jews were prominent in the Prague Spring uprising in 1968 against Soviet rule. The only member of a Czech delegation to Moscow to voice opposition to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia was a Jewish physician named Frantisek Kriegel. The suppression of the uprising by the Soviet Union was accompanied by an anti-Semitic and anti-Zionist campaign. Ruled by a hard-line faction of the Communist Party, Czechoslovakia served as a conduit for providing explosives and training to Arab terrorists.

With the overthrow of the Communist regime in 1989, the Czech republic reemerged as a friend of Israel. The first president of post-communist Czechoslovakia, dissident playwright Vaclav Haval, extended his hand in friendship to Israel. In April 1990, he visited Israel with a large delegation of Czech Jews and established closer relations between the two states. In 2010, now retired from politics, he co-founded with former Spanish Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar, the Friends of Israel group of international political figures. Haval’s successors have maintained a friendly relationship with Israel.

Although anti-Semitism exists in the Czech republic, there has traditionally been a lower level of hostility towards Jews and greater social acceptance than what existed in other countries of Eastern and Central Europe. In 2013, there was even a pro-Israel rally in the Czech Republic.

In light of the tragic historical parallels and contemporary friendship, it is no surprise that the Czech republic provided the only head of state to attend the funeral of Ariel Sharon. Sharon’s resolve that Israel should rely on itself for its defense and his disregard for international norms when necessary was a repudiation of the passivity of Jews in Europe and of capitulation to the threats of an aggressor.

Romanian Jews’ Twist of Fate

Romania’s decision to send a high level representative to Sharon’s funeral has equal historical resonance to the Czech representation, but with a different message. Romania’s historic relationship with the Jews is complicated. Romania has a long tradition of virulent anti-Semitism, yet a large Jewish population resided there and for a time flourished.

Romanians suffered greatly in World War I. In the turmoil that followed, native fascist groups emerged and gave full vent to the anti-Jewish sentiments common among elements of the population.

With the rise of National Socialism in Germany, these fascist groups gained traction. In 1940, when General Ion Antonescu assumed power, he brought the most significant fascist group, the Iron Guard into the government. In January, 1941, Iron Guard legionaires carried out a horrific pogrom in Bucharest slaughtering 125 Jews, including children. Fearing the stability of the state was being undermined, Antonescu violently suppressed the Iron Guard. But the campaign against the Jews continued. In July, a more devastating pogrom in Iasi took the lives of up to 15,000 Jews.

With the rise of National Socialism in Germany, these fascist groups gained traction. In 1940, when General Ion Antonescu assumed power, he brought the most significant fascist group, the Iron Guard into the government. In January, 1941, Iron Guard legionaires carried out a horrific pogrom in Bucharest slaughtering 125 Jews, including children. Fearing the stability of the state was being undermined, Antonescu violently suppressed the Iron Guard. But the campaign against the Jews continued. In July, a more devastating pogrom in Iasi took the lives of up to 15,000 Jews.

In 1941, Romania joined with Nazi Germany in the attack on the Soviet Union. In the territory overrun by Romanian troops, Jews were hunted, rounded up and either massacred or allowed to perish in camps lacking food or shelter. In the death camps of Transnistria and Bessarabia more than 300,000 Jews perished. In Odessa, in response to the assassination of a Romanian general, the Romanian army went on a rampage and slaughtered every remaining Jew they could find in the city.

But, in a twist of fate, the situation for the Jews of Old Romania (the traditional borders of Romania that exclude annexed territories of Northern Transylvania and Bessarabia) improved. The pogroms of 1941 represented the apogee of anti-Jewish violence in Old Romania. For complex reasons, for the remainder of the war the Antonescu government protected the Jews of Old Rumania, even as they continued to persecute Jews in captured territories.

As a result the Jews of Old Romania survived in greater numbers than anywhere else where Nazi influence prevailed. Ironically, this was due to the fact that the Romanian government, as a voluntary participant in Germany’s war of aggression against the Soviet Union, did not elicit direct German control. The fate of the Jews residing in Romania was left in the hands of the Romanian authorities, who became increasingly uncertain of German victory and worried about their own fate.

The battle of Stalingrad proved to be a turning point. The Soviet counter-offensive in November 1942 that eventually encircled and destroyed the German Sixth Army, first punched through and obliterated two Romanian armies. The magnitude of Romanian losses, more than 100,000 troops killed or missing in just a couple of weeks, jolted Romanian political leaders and caused them to reconsider their unqualified support for the Nazi regime and its policies. For the remainder of the war, the Romanian government played a duplicitous middle game, maintaining its ties to Nazi Germany, but putting out feelers to the West and greased by bribes, extending some protection to Jews there.

On June 21, 1944, the Soviet Union launched the largest offensive of the war, Operation Bagration, directed at Germany’s most powerful army concentration. In just over three weeks of intense combat, nearly half a million German troops perished or disappeared into Soviet prison camps. As the Germans fell back to re-form their lines, the Soviet forces crossed into eastern Europe and in late August, invaded Romania. In a week, the Romanian army capitulated, switched sides and began attacking the retreating Germans. For the surviving Jews of Romania, the nightmare was over.

After the war ended, in eastern Europe, within the borders of Romania remained the largest number of Jews. 428,312 survivors were registered in 1946. Over the next few years, most immigrated to Israel, so that Romanian Jewry contributed the single largest flow of immigrants to the nascent state of Israel from 1948-1950.

As a result of this extensive Jewish emigration from Romania to Israel, the Romanian government, both under Communist rule and since, maintained a relationship with Israel. During the Cold War, Romania was the only East-bloc nation to not break off relations with the State of Israel. It served as a link between Israel and the rest of the East-bloc. In the 1980s, the hard-line Communist regime even initiated trade relations with the

Jewish state.

Since the fall of the Communist regime in Romania, relations between the two countries have grown closer. A crash in 2010 of an Israeli helicopter revealed the extent of this cooperation. The Romanian government was allowing the Israeli air force to train in Romania.

But twenty five years after the fall of Communism, Romania remains an economically struggling country. As Israel has prospered, a flow of Romanians (non-Jews) have sought work in Israel. Several were victims of Palestinian terrorism during the Second Intifada.

The establishment of the Jewish state fundamentally transformed the historic relationship of Romania and Romanians with the Jews. Although Romania’s Jews were prominent in the professions and as successful merchants, this did not endear them to the Romanian people. Jews were viewed with suspicion, and subject to the violent whims of turbulent Romanian society. But with the establishment of Israel, a more normal relationship has developed between two sovereign peoples based on respect and shared interests. One might even posit, as Herzl had envisioned.

The establishment of the Jewish state fundamentally transformed the historic relationship of Romania and Romanians with the Jews. Although Romania’s Jews were prominent in the professions and as successful merchants, this did not endear them to the Romanian people. Jews were viewed with suspicion, and subject to the violent whims of turbulent Romanian society. But with the establishment of Israel, a more normal relationship has developed between two sovereign peoples based on respect and shared interests. One might even posit, as Herzl had envisioned.

The unique historical relationships the Jewish people and the State of Israel has with the Czech republic and the Republic of Romania was reflected in the decisions by these two eastern European states to send high level representations to the funeral of Ariel Sharon. Israelis and friends of Israel should be reminded that the present and future are shaped by history and the funeral of a controversial, but patriotic figure is a good time to take notes.

1 Katerina Capkova, p. 34, “Czech, Germans, Jews: National identity and the Jews of Bohemia”, published by Berghahn books, 2005