Stories of exile and return are bedrock motifs of the Western literary tradition. Think of The Odyssey, which chronicles Odysseus’s long exile and tortuous return to Ithaca, or the exile and return of the Hebrews, down to Egypt and back up to the Promised Land.

Children’s picture books often pattern themselves on this trope: In Maurice Sendak’s classic Where the Wild Things Are, Max, punished for his mischievous antics, sails off to the land “where the wild things are,” enjoys his liberating adventure, then returns home, where his supper, like Odysseus’s wife Penelope, is waiting for him.

Palestinian children’s books often invoke the motif of exile. Many are designed to inspire empathy among young readers for a sympathetic child protagonist, with the longer-term goal of embedding in the young reader’s mind an enduring image of Palestinians as victims and Israelis as oppressors. But whereas Odysseus returns home triumphant, and the Hebrews make their way through the Reed Sea and across the Jordan, the poor Palestinians are left in limbo.

The story of Aya Ghanameh’s These Olive Trees is simple: In a refugee camp, young Oraib (modelled on the author’s eponymous mother) accompanies her own mother as she harvests the olives growing just outside the camp. Oraib tastes the bitter olives, thinking that sometimes “she finds joy in the bitterness.”

“In the refugee camp,” the story tells us, the olives can turn into many things: kindling, ornaments and tools, cooking oil and soap. And like the olives, the camp can surprise the unhappy child, offering “happiness in the sorrow around her,” like the pleasure of helping a boy build a kite.

But one day, the family must gather the olives before they ripen, for once again, they must move. Having been displaced by the war once already, now they are forced to flee Balata camp, near Nablus, towards an unknown destination.

Oraib picks up an olive pit and plants it: “Although olive trees take a long, long time to grow and even longer to produce olives, Oraib decides that for once, she will be patient.”

“Wait for me,” she says to the olive pit. “One day, when we’re older, I’ll return to you for harvest.”

The message, at least to the adult reader, is clear: We Palestinians may have been chased out of Palestine, but we’ll be patient and, some day, we will return. Israel (a word never uttered by the author, who degrades it instead as “the occupying state”) is temporary.

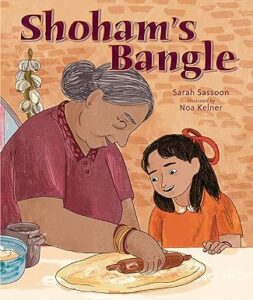

A Jewish picture book published just two years before These Olive Trees has a strikingly similar structure. Shoham’s Bangle opens in Iraq, where young Shoham loves watching her Nana Aziza cook. When Shoham bakes date cookies, she uses one of her grandmother’s bangle bracelets to cut them out.

The family’s idyll comes abruptly to an end when they are forced to leave Iraq, with only one suitcase for all seven of them – and no jewelry. But just before their departure, Nana Aziza bakes a pile of pitas, which she entrusts to young Shoham for the journey.

The family boards the plane, and when it touches down in Israel, Shoham’s sack of pitas is opened. As she bites into hers, her teeth strike something hard, her golden bangle – “[t]o remember where we came from, Shoham,” explains her Nana.

Two children exiled from home, both with talismans of their roots. But that is where the resemblance ends.

Ghanameh’s author’s note delivers a false Palestinian narrative to vulnerable young readers. It is also cleverly crafted with an eye to inducting the adult reading the story aloud into the Palestinian narrative. Both will be told that “[t]he story of my family’s Nakba was only a fraction of a broader campaign to empty every Palestinian city of Palestinians” (My emphasis).

As (left-wing) Israeli historian Benny Morris explains: “[A] ‘policy of expulsion’ in 1949 to 1956? If there was such a policy, why was it not implemented? Why did the number of Arabs in Israel increase steadily, in part due to infiltration of refugees back into Israel who, over the years, received identity cards?” Using primary-source documents in the Haganah Archive, the IDF Archive and the Israel State Archives, Morris states emphatically, “[T]here was no policy of expelling ‘the Palestinians’ and . . . the Haganah did not expel Arabs prior to April 1948 (with the exception of Arab Caesarea, where the motivation had nothing to do with the struggle with the Arabs).” In fact, the government’s policy was the policy of the Partition Plan, and that was not a plan for ethnic cleansing, but for accepting the presence of a large Arab minority.

The author’s note falsely claims that the plan “to empty every Palestinian city” included Haifa. Not true. Morris again: “In Haifa, it was the Arab leadership that called on its population to evacuate (the Jewish mayor, Shabtai Levy, and the Histadrut labor federation activists asked them to stay).”

There are two more libels – that “[t]o this day, Palestinians are being forcibly removed from their homes” and that since 1948, “the occupying state and settlers have cut down and destroyed more than eight hundred thousand olive trees.”

It’s unclear whether the author is referring to home demolitions or evictions. Demolitions related to terrorism can be appealed and are governed by decisions of Israel’s Supreme Court. Demolitions of homes built illegally, according to investigator Justus Reid Weiner, are “not arbitrary, but are governed by ‘[p]recise and demanding procedures . . . in all parts of the city.’” Nor are home demolitions restricted to Arab homes; on January 9, 2024, the IDF destroyed illegally-built Jewish homes on the West Bank.

Stories of evictions – for example, in Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem – are a staple of anti-Israel propaganda, but often don’t withstand scrutiny; as Palestinian human rights activist Bassam Eid explains, the Arab families in Sheikh Jarrah are occupying Jewish-owned homes for which they refuse to pay rent.

The propaganda war over the destruction of olive trees is unrelenting, with each side offering photographic evidence of the other side’s destruction of trees. Ghanameh’s accusation is not sourced. However, between 1967 and 1993 in the West Bank and Gaza, “under Israeli rule, average olive production increased by 83 percent,” from 44.5 thousand tons to 81.4 thousand tons. This could not have happened if Israel was bent on destroying Arabs’ olive trees.

Sarah Sassoon’s author’s note offers a telling contrast to Ghanameh’s. It recounts the Jews’ millennia-long presence in Iraq (from the days of Ezra the Scribe, whose tomb sits on the banks of the Tigris River). Then, comes the story of Operation Ezra and Nehemia — the 1951 airlift to Israel. While Sassoon evokes her family’s wariness of the authorities, she points no fingers, even though the atmosphere for Jews living in Iraq was strained by fear of a reprise of the Farhoud pogrom ten years earlier. Despite her family’s trauma, Sassoon’s story of loss ends on a note of optimism: “[I]t’s not about the homes we leave, but about the homes we rebuild.”

These Olive Trees promotes a negative image of the Other and emphasizes Palestinian passivity. With its inaccuracies, the book is unfit for use in schools and should be rejected by libraries for its libelous accusations against that unnamed “occupying state.” It is shameful that Viking lent its name to a subtle, but pernicious, form of anti-Israel propaganda.