- 671

- 682SHARES

One of the lessons in the children’s story “Uncle Meena” is about coexistence. The story’s eponymous protagonist, the wise and genial Uncle Meena, models an unprejudiced acceptance of people of all faiths. Or, rather, almost all faiths.

At one point in the short story, the narrator, Uncle Meena’s young niece Noora, hears about the friendships her uncle made while abroad in the United States. “I have friends from many faiths,” Meena explains. Muslims. Christians. Hindus. And a subsection of Jews whose foreign-policy positions render them acceptable.

“Uncle Meena,” by Palestinian author Ibtisam Barakat, is being promoted in English classes in U.S. public school districts. As a chronicle of the points of view of fictional Palestinian characters, the story is unimpeachable. Who is to say Grandma isn’t upset because her belief that she wouldn’t be granted access to the al Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem? Who is to say Noora doesn’t view Palestinians who engage in violence as “freedom fighters”? Who’s to say Meena doesn’t believe Palestinians are “Indians” and Israeli Jews are “cowboys” with no real connection to the land of their forefathers? The characters belong to the author. She gets to decide what they have experienced and what they believe. And this, Barakat conveys to her readers, is what the characters believe.

But as a story assigned to young readers in public school classrooms, there are serious concerns about its messages on the Arab-Israeli conflict, Jewish history, and American Jews. Teachers and parents should note the following about Barakat’s tale.

The Conflict

It’s not only that “Uncle Meena” promotes a one-sided, misleading narrative on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict – though it certainly does this. The Palestinian author and her Palestinian characters, for example, fail to mention terrorism faced by Israelis, even as they criticize Israeli security measures that arose in response to such terrorism. Perhaps that’s understandable. They have the option to present their narrative without interference from inconvenient or contradictory information, and they seize the opportunity.

But American students pushed toward the view that Palestinians killed in conflict with Israel have “died in the struggle for our freedom,” as the narrator puts it, will gravely misunderstand the conflict if they’re not also exposed to the reality that many of these so-called freedom fighters were heavily armed, illiberal members of fundamentalist, antisemitic terror organizations that, in an effort to wipe Israel off the map, target Jewish civilians in flagrant violation of international law. There is not even a hint of this reality in the story.

Noora, meanwhile, might not know or care that Grandma can generally pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque during Ramadan; or that after an era of largely free travel, restrictions on Palestinian passage from the West Bank into Israel were imposed in response to Palestinian violence during the first intifada, and later were part of an agreement between Palestinian and Israeli leaders to allow for greater Palestinian autonomy; or that the Temple Mount on which the al Aqsa Mosque stands is the holiest site in Judaism; or that some Palestinians harass and curse Jews visiting this holy site. These are key elements of the story — just not this story.

Noora’s ignorance or indifference isn’t reason enough to impose the same onto American school children. To introduce the Arab-Israeli conflict only from the view of one side’s partisan is to indoctrinate and mislead students. This is what Barakat’s story does, as does an anthology published by Amnesty International that includes “Uncle Meena” but no mainstream Jewish perspectives, and as do some teachers who introduce Barakat’s story in their classrooms.

The Story of the Jews

But again, it’s not only that the story promotes a slanted, misleading narrative on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. “Uncle Meena” also imposes an ahistorical understanding of Judaism itself, one that rewrites the annals of Judaism and treats with contempt the Jewish community’s identity.

That contemptuous view, promoted by the beloved Uncle Meena and endorsed by the relatable Noora, holds that Palestinians are like Native Americans (or “Red Indians,” as the story dubs them) while Israeli Jews are akin to white, colonizing cowboys. This is the central theme of “Uncle Meena.”

One purpose of the analogy is to give children the false impression of an ongoing genocide in the Holy Land. Indeed, by explicitly referring to the genocide of indigenous American tribes at the same time that it pushes the metaphor of Palestinians as Indians, the story insinuates Israeli Jews are guilty of a kind of Holocaust, an outrageous and inflammatory charge not just because it presents the rapidly-growing Palestinian population as being destroyed, but also because it amounts to a form of “Holocaust inversion” — something that historian Deborah Lipstadt characterizes as a form of “soft-core” Holocaust denial. To call Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians a genocide, Lipstadt has explained, “is to deny what a genocide is.”

A 1,500-year-old mosaic, part of a Jewish synagogue in Jericho, depicts a menorah over the Hebrew text, “Peace unto Israel.”

The broader ramification of the analogy is a denial to Jews of their own Jewishness, by way of a denial of Jewish history. By charging that Jews are analogous to cowboys, the Palestinian author teaches that, just as cowboys were strangers to what they viewed as “the new world,” Jews are strangers to their ancestral homeland.

Yes, Jews and historians alike recognize that the homeland in question was previously known as Israel and Judah, and that the latter name is no less than the origin of the word “Jews.” Yes, Jews and historians understand that the land has always been holy to Jews, and is home of the holiest cities and most sacred sites in Judaism. Yes, Jews and historians know that archeological evidence unequivocally points to Jewish roots in the land. Yes, they are aware that Jews dwelled on, were expelled from, and were massacred in this homeland long before – and long after – the Arab and Muslim imperial conquest. Yes, both in the homeland and the diaspora, Jews continued to pray in the ancient language of the land with prayers that longed for the land, and continued to celebrate the ancient festivals of the land based on the ancient calendar of the land, without interruption. “Cowboys” they are not.

But no, Barakat doesn’t want Meena, Noora, or her readers to grapple with that reality. Again, the author is free to “talk over” Jews. She is free to deny Jews their self-identity and historical reality as originating from, and bonded to, the Holy Land. But whatever her characters are made to believe, it is unconscionable to leave school children with that lesson. The analogy between Jews on their homeland and colonizing cowboys amounts to Judaism denial — and it puts an anti-Jewish tale at the center of the story.

Conditional Acceptance of American Jews

There is another anti-Jewish lesson in Barakat’s story, arguably worse than its Judaism denial, that is embedded in the protagonist’s comments about coexistence.

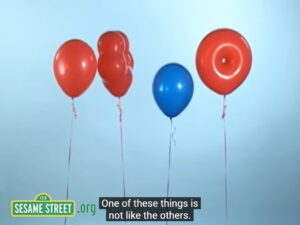

Uncle Meena’s account of his friendships abroad singles out American Jews as clearly as Sesame Street singled out a blue balloon among red ones.

As Noora seeks her uncle’s wisdom about conflicts between peoples, Meena shares with her his experience living in the United States. “I have friends from many faiths: Muslims, Christians, Hindus, pagans, and also some Jews who care about Palestinians and want the occupation to end” (emphasis added).

As another pedagogical program would put it, one of these things is not like the others.

The comment Barakat puts into the mouth of her protagonist is particularly chilling in that it targets young Jews as individuals. Meena’s words don’t just leave readers with the impression that Jews stand out as a people who, with “some” exceptions, don’t tend to care about the heroes of the story. (Meena is hardly the first to “admit the existence of ‘good Jews’” while communicating an anti-Jewish message.)

It also teaches students to treat their Jewish friends and neighbors — the subject of the passage is American Jews — differently than they would treat others. It tells non-Jewish students that acceptance of their Jewish classmates, and only the Jewish ones, should be conditional on them being subject to a foreign policy litmus test. And it instructs Jewish students to likewise question their own integration among their peers.

In short, what looks like feel-good lesson on coexistence seems designed, rather, to manipulate young Jewish boys and girls by threatening what many adolescents care about most: their social value and self-worth.

Are Anti-Jewish Lessons Defensible?

Again, Barakat is entitled to her narrative. She is entitled to dismiss Jewish history. She is even entitled to put American Jews in the dock. Publishers are entitled to print as many copies of the book as they please. Bookstores are entitled to stock all of those copies.

But is this the kind of story that should be assigned in grade schools?

There are plenty of other ways to introduce students to Palestinian culture, to the Israeli Jewish experience, or the conflict between the groups, without at the same time rewriting Judaism and sacrificing Jews’ sense of inclusion. At the same time, there are plenty of stories that wouldn’t be assigned in a classroom. (“Uncle Meena” isn’t exactly a literary classic, after all.)

It isn’t enough for school officials to point out that the story is fictional, if it is also harmful; or that it exposes students to aspects of a different culture, if it approvingly highlights precisely those aspects that demean another culture.

While it might be tempting to think the solution is to assign a countervailing story alongside this one, what exactly does “balance” look like here? Should we expect the assignment of a story that that denies Palestinian and Muslim history? Or one that teaches students to be suspicious of their American Muslim classmates, or that teaches young American Muslim students to be suspicious of their own Muslimness? Those hardly seem like compelling options.

And so parents are in a bind when teachers turn in this way to inappropriate and inflammatory lessons on controversial subjects. Ideally, those entrusted with educating our children would put in the effort necessary to avoid “Indoctrinating Our Youth” — and many educators do manage to steer clear of political propaganda. But “Uncle Meena” is a reminder that communities must review the presentation of the Arab-Israeli conflict in their school systems in order to promote scholarly, accurate materials and to remove factually inaccurate and biased curricula.