Apparently, it’s an occupational hazard for Christian Bible scholars to think ill of Israel and its Jewish citizens. This tendency doesn’t afflict every Christian scholar of the Bible, but the fact is, some of the people who should be most committed to preaching a Biblical message of love and forbearance have a difficult — if not impossible — time offering much consideration to Israeli Jews. Some of these scholars say and write hateful falsehoods about Israeli Jews who attempt to defend themselves from hostile attacks from their Palestinian neighbors, many of whom are motivated by an virulent antisemitism rooted in the Koran and Islamic doctrine.

New Testament scholars in particular are vulnerable to the temptation of casting modern day Jews into the frame of Jewish and Roman villainy laid out in the Gospels. By using these frames to interpret the conflict, these Christian scholars do not promote love or peace, but instead broadcast a contemptuous and hateful commentary on the Israel-Palestinian conflict that demonizes Israelis and gives Palestinians a pass.

This scripturally-rooted narrative of Jewish villainy offered by Christian scholars like Naim Ateek, Walter Brueggeman and Gary Burge has helped pave the way for a resurgence of antisemitism in the Western church. This narrative has engendered indifference to the suffering Israelis have endured over the past several decades and given license to Palestinian violence and hostility against the Jewish people.

It is as if the early church fathers who sought to destroy the prestige of the Jewish people in order to promote the ascendancy of Christianity have come alive again in the 21st century to work their evil against the Jewish state.

Modern-day practitioners of these old/new polemics ignore the warnings offered by Jules Isaac in his book, The Teaching of Contempt. In this text published in 1962, Isaac laments how anti-Jewish hostility remained a persistent aspect of the Christian faith, despite numerous warnings about the evils of antisemitism from church leaders. “There is a Christian anti-Semitism,” he wrote. “Whether conscious or unconscious, it is perennial and virulent, of great scope and intensity.”

“Oozing Darkness”

Bruce Fisk (Photo: Baker Publishing Group)

Contempt for Israeli Jews, especially those living in the West Bank, is sadly evident in the writings of Bruce N. Fisk, a well-known (and well-regarded) New Testament scholar, from Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California. Fisk, who is listed on the school’s website as a professor of religious studies, visited Israel during the early 2000s and apparently became radicalized by the Palestinian suffering he witnessed.

While visiting the Holy Land in 2006, Fisk watched a propagandistic film (“The Iron Wall”) that condemned the construction of Israeli homes and IDF actions in the West Bank. After seeing the film (which omitted any reference to the Arab refusal to negotiate a land-for-peace deal after the Six Day War —a deal that would presumably have prevented Israelis from living in the West Bank) Fisk wrote the following:

For now I can only ask: how can Jews so zealously religious be so hateful and malicious? Is this the same righteous zeal that drove Phinehas the priest to drive a spear through the sinful Israelite and his Midianite consort (Num. 25:6-13)? The same indignation that compelled Saul (Paul) to set out for Syria to seize and bind Jewish converts to Christianity (Acts 9:1-2)?

Or is this something more sinister? What oozing darkness flows within people who burn homes, destroy property, beat old women and stone children? Equally, what kind of society knows this goes on and does nothing about it? And what kind of world knows about such things and offers its tacit approval?

Anyone who inserted the word “Muslims,” or “blacks” — or the name of any other ethnic group — into the place where Fisk has placed the word “Jews” would rightfully be called a bigot. But “bigotry” does not begin to describe the problem with this passage, which places religious Jews living in the West Bank beyond the pale of humanity. Fisk portays them as having an “oozing darkness” flowing within them.

By portraying Israeli actions in a cosmological “oozing darkness” Fisks distracts his readers from concrete, real-life circumstances that Israelis on both sides of the Green Line had to endure during the Second Intifada.

Yosef Hartuv (Photo: Dexter Van Zile)

Virtually every Israeli knows someone who was killed or maimed by Palestinian acts of terror during the Second Intifada says Yosef Hartuv, who blogs at Love of the Land. During the Second Intifada, Israelis were killed at weddings and Bar Mitvahs, Hartuv reports. “They were blowing up event halls.” Such terrorism had real psychological impacts on Israelis and for Fisk to speak with such contempt for Jews in light of these psychological impacts is profoundly troubling, Hartuv said.

Citing a list of Israeli victims of terror maintained by the Israeli government, Hartuv said, “I know a lot of the people on this list. There are hundreds of them. It has a huge impact on Israeli attitudes.”

Instead of acknowledging the suffering Israelis have endured, Fisk treats Israelis, especially those living east of the Green Line, as otherworldly monsters in a science fiction movie who lack the right to breathe in air on planet earth, much less live in the West Bank. He portrays Israeli settlers in the West Bank as a cosmological repugnant other inhabiting the opposite side of an unbridgeable chasm that separates them from the rest of humanity.

“Israel as Rome”

While Fisk has been typically very rough on Israeli Jews in his blog, he simply cannot muster very much outrage when dealing with Palestinian violence. In another entry titled “Israel as Rome,” Fisk writes:

I do not excuse the suicide attacks and summary executions perpetrated by militant Palestinians any more than I endorse the atrocities of the dagger-wielding Sicarii during the Jewish War. But the Palestinians, like the Jews of Roman Judea, are a people under occupation.

Unlike the Jews living under Roman occupation, the Palestinians were offered a state during negotiations at Camp David in 2000 and Arafat said no. Arafat also said no to an even better offer in the form of the Clinton Parameters put forth a few months later by U.S. President Bill Clinton.

In his ongoing effort to portray Israeli Jews as the villain, Fisk omits historical events that would undermine his depiction of Israel as playing “the imperial role once filled by Rome.”

Hitchhiker Book

Fisk’s othering obsession with Jewish villainy is a central feature of his 2011 book, A Hitchkihker’s Guide to Jesus: Reading the Gospels on the Ground published by Baker Academic Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, a publishing house that caters to Evangelical Protestants in the United States.

The text, which is used in a number of college level classes in Christian schools throughout the U.S., offers a fictionalized account of a recent college graduate’s visit to the Holy Land and his search for the historical Jesus in the land. Fisk reports that many of the protagonist’s “exploits are adapted from my own (mis)adventures in the Middle East,” and that “Others are made up.” The goal of the trip to the Holy Land described in the protagonist’s voice is “to get close to the sources of a religion and perhaps rescue my own faith from the ashes of modernity.”

The search for the historical Jesus is the overt narrative in Fisk’s text, but there’s another subconscious and pernicious narrative present in the book. It’s the story of a young, innocent, and naïve Christian coming face to face with evil Jews in the Holy Land just as Jesus did in first century Jerusalem. When Jews appear in Fisk’s narrative, they almost invariably come off as bad, powerful people who do mean things to Palestinians for reasons that Norm, his literary alter ego, can’t seem to fathom.

For example, Fisk’s book opens with Norm being told to lower his trousers by El Al security before getting on the plane in an unnamed city in the United States. No context is provided as to why El Al would subject Norm to such intense scrutiny. The fact is that a planeload of Jews returning to Israel presents an attractive target for a hijacking or other terrorist attack.

And when Norm arrives in Israel and walks in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City on Friday afternoon, he sees a group of religious Jews walking toward their homes for Shabbat dinner. They remind him of his dog, named after the dwarf Gimli in Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings. Here is what Fisk writes:

Friday afternoon found me in the Jewish Quarter. I surveyed the sea of men bobbing in prayer at the wall and then explored a maze of tidy stone alleyways where tidy families marched in tidy processions toward the homes where they would share a Shabbat meal. Reminded me of Gimli circling the carpet before her nap. [Note: This passage is accompanied by a photo of Orthodox Jews walking in the Old City.]

It beggars belief that a passage comparing a group of Jews in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem to a dog — named after a dwarf no less — got past the editors at Baker Publishing Group, but it’s not the only unfortunate comparison that made it into Fisk’s text. Toward the end of the book, Fisk describes an Israeli settler pacing like a “caged ferret.” (More about that below.)

The beginning of Norm’s quest to find the historical Jesus is delayed by “unrest” in Bethlehem, which he describes as follows:

In a military operation to arrest “wanted” Palestinians, Israeli forces had killed an eighty-three year old woman. Next came street protests, rock throwing, and tear gas so Bethlehem was placed “under closure,” meaning none could enter or leave. I wonder if Herod imposed a curfew on Bethlehem when his troops entered to find the “wanted” newborn who threatened his rule.

Here Fisk is deploying the “Israel as Rome” trope he used in the blog entry described above. Fisk’s use of scare quotes around the word wanted seems to convey a sense that the Israelis are being irrational and evil in their desire to capture the Palestinians, just as King Herod was in his desire to kill the infant Jesus, which led him to murder dozens of young children in Bethlehem. The implication of Fisk’s narrative is that the Palestinian that Israelis were trying to capture were as innocent, powerless and benign as the infants Herod had killed.

Instead of providing readers with information regarding the circumstances surrounding the elderly woman’s death, Fisk introduces the image of King Herod to make the Israelis seem evil and malevolent, just like the man who sent Roman soldiers into Bethlehem to kill all the infants in the city. What Fisk has done is place real people — modern-day Israelis — into a reenactment of Christianity’s founding narrative that highlights their allegedly malign and evil nature. The Jewish victims in the Gospel of Matthew have been transformed into executioners into Fisk’s book.

Fisk uses the Slaughter of the Innocents to highlight Jewish villainy when he describes the Siege of the Church of Nativity that took place in Bethlehem in April 2002. He describes Franciscan monks who:

were trapped in the church compound—“voluntary hostages,” they called it—with about two hundred Palestinian militants for some forty days back in April of 2002. Rather gutsy those Franciscans. Nonviolent. Nonpartisan. Ready to die to protect a holy site. They went without food, water, medicine, and electricity, hoping to prevent what some might call another “slaughter of the innocents.” It worked.

Fisk’s suggestion that the gunmen who took refuge in the Church of the Nativity qualified as “innocents” is simply an insult to the Israeli and American Jews who were murdered in the attacks organized or perpetrated by13 terrorists who took refuge in the church during the siege. Given the presence of members of Hamas and Fatah’s Tanzim Brigade in the group of 200 gunmen who took over the church, it is simply irresponsible for Fisk to unreflectively pass on the notion to his readers that the Franciscans stayed in the church “voluntarily.”

What Fisk has done in his description of the siege is to affirm the moral superiority of Christians in the Holy Land by portraying Israeli Jews as the modern-day equivalent of the Roman Empire and portraying Palestinian terrorists as akin to innocent Jewish babies slaughtered by King Herod.

The question Fisk’s Christian readers need to ask themselves is a simple and stark one: Is this the proper use of the Gospel — to demonize modern-day Israelis and downplay the horror of Palestinian terrorism, all in an effort to make Christianity and its adherents look good? Does casting religiously-motivated settlers into the frame of the “repugnant other” (as described by Susan Harding in 1991) qualify as peacemaking?

Hebron Distortions

Eventually, Fisk’s protagonist does find a Jew he admires, an activist named Yehuda who works for an Israeli organization called Breaking the Silence who tries to lead a tour through the city of Hebron but is stopped by the IDF at the insistence of Israelis who live in the city. Predictably enough, Fisk casts Yehuda in the role of Jesus of Nazareth as he stands in opposition to evil and malevolent Jews of modern Israel. “Both Yehuda and now Yeshua then spoke out against injustice and rejected violence, and both clearly posed no physical threat to the security of the realm.” Fisk continues:

The official representatives of God and Caesar decided, nevertheless, that the prophets’ agenda of truth telling and reconciliation was too provocative, too dangerous. For Yehuda the result was a canceled tour; for Yeshua a death sentence. If each one was gracious in defeat, it was because he was convinced that one day a judge would vindicate his cause.

Equating an activist from Breaking the Silence to Jesus Christ himself is pretty outrageous. The organization does a pretty good job of provoking Westerners into embracing an anti-Israel narrative but has little credibility amongst Israelis. And why should it? Yehuda Shaul, the man Fisk lionizes, has falsely accused Israeli settlers of poisoning wells in the West Bank, and the organization he leads has been criticized for broadcasting unsubstantiated accusations against Israeli soldiers and for taking foreign money to finance its work with strings attached — all things Jesus did not do. To be fair, Fisk’s book was published several years before these controversies hit the news, but they do shed some light on the sources he relies on for his information.

In addition to irresponsibly equating Yehuda Shaul to Jesus Christ, Fisk mischaracterizes the reality in Hebron, home to several hundred Israelis and approximately 200,000 Palestinians. Fisk describes the city as “bearing the scars of two modern tragedies” the first being the murder of 67 Jews in the city in 1929 and the second being the massacre of 29 Palestinians by Baruch Goldstein in 1994. Fisk reports that in addition to killing 29 Palestinians, Goldstein “wounded one hundred fifty before he was subdued.”

Here, Fisk omits an important detail — that Goldstein wasn’t just “subdued” but beaten to death after his heinous crime. Fisk includes this fact of Goldstein’s death in a blog entry but not in his book. Why omit it? Nobody is going to judge the Palestinians too harshly for killing Goldstein in light of the horrific crime he had just committed.

Is Fisk trying to sanitize the Palestinian narrative from acts of violence even when that violence is directed against the perpetrator of a heinous crime?

Maybe so, because Fisk’s narrative is all about Jewish power and the problems that come with it. For example, on the same page, Fisk writes that “no where else are so many Israeli soldiers charged to protect so few (armed) Israeli citizens from the (largely unarmed) Palestinian population.”

Yes, there are a lot of Israeli soldiers in and around Hebron, which is one of the largest cities in the West Bank, just like there are a lot of Israeli soldiers near Bethlehem. Why shouldn’t there be? Hebron, which has a population of 200,000 or more, is a Hamas stronghold in the West Bank.

Moreover, there is a community called Kiryat Arba of 8,000 or so Israelis nearby. Residents of this city have been attacked by Palestinian terrorists. But Fisk suggests that the only reason the Israeli soldiers are in Hebron is to protect the several hundred Jews who live in the city.

There are a lot of reasons to have a large contingent of Israeli soldiers near one of the largest cities in the West Bank. Even if there were no Israelis at all living in Hebron, there were would still be soldiers in the area.

And Fisk’s statement that the armed Jewish inhabitants of Hebron are facing off against a “largely unarmed” group of Palestinians is a dishonest distraction from Palestinian violence. The fact is, Hebron has been the scene of ongoing terror attacks against Israelis going back decades. For example, in 1980, six Israeli teenagers were killed by group of Palestinian terrorists that included the recently elected mayor of Hebron — who bragged about his involvement in this attack to a laughing audience at a campaign appearance prior to his election.

Despite Fisk’s effort to portray the residents of Hebron as a peaceful bunch, the previously mentioned list of Israeli victims includes a number of Israelis who have been murdered by Palestinian terrorists in or near the city of Hebron. The list includes a 10-month old baby, Shalhevet Pass, who was killed by sniper fire on March 26, 2001 — and many others. Yosef Hartuv reminds readers that there have been many other attacks in Hebron, stabbings especially, that have taken place over the years that didn’t get much attention. “If you weren’t killed,” he said, “it didn’t make the news.”

And despite all these attacks and other acts violence endured by Israelis in and near the city of Hebron, Fisk dares to write about the “largely unarmed” Palestinians who live in the city.

While Fisk downplays Palestinian violence and hostility toward Israelis in Hebron, he works assiduously to highlight and emphasize Jewish villainy and truculence. He describes a confrontation between a group of Israelis and a tour bus operated by the previously mentioned group Breaking the Silence. Speaking through Norm, Fisk describes journalists on the bus as “synoptic Evangelists scribing an improbable gospel” as they document the heroics of two BTS activists Mikhael and Yehuda as they are taunted by their fellow Jews. Fisk writes:

Midway through the standoff a young settler caught my eye. Maybe fourteen years old, he paced beside the bus like a caged ferret. When he spotted me, he stared back briefly, then drew several fingers across his throat. My first ever death threat.

Note the ugly comparison between an Israeli boy who (like Israelis on both sides of the Green Line) has spent most of his life in the shadow of Palestinian incitement and anti-Jewish violence and a “caged ferret.”

Fisk presents his readers with a protagonist who lacks the knowledge and moral imagination to understand why a young Israeli teenager living in Hebron might also be angry at Palestinians and their allies in the so-called human rights movement.

To make matters worse, Fisk has his protagonist describe a young Israeli Jew as a rodent. This is inexcusable. Throughout the text, Norm is held up as a credible example for other young Christians to follow as they struggle with the meaning of scripture in the modern era. This can only serve to legitimize the contempt for Israeli Jews that Fisk uses Norm to broadcast.

On the next page, Fisk describes a confrontation Norm/Fisk has with another Israeli teenager as he walks onto Shohada Street — a street in Hebron that has been closed to allow Jews to be able to walk freely without being stabbed or shot by their neighbors —as they have been so many times in the past. Fisk writes:

A lone boy moved toward me. Long side curls handing below his blue knit cap identified him as a settler. I didn’t understand his Hebrew, but the blow he delivered to my shoulder required no translation. Thankfully he was alone and about thirty pounds lighter than I. Not pleased to be threatened twice in one day, I took his picture with my cell and turned away. [Note: The picture Fisk describes is published on the previous page, near the text that describes the other Israeli teenager as a “caged ferret.]

The encounter put a new face on the tragedy. The boy’s orange T-shirt read NEVER AGAIN, clear reference to the obscene horrors of the Holocaust, when Jewish property was seized or destroyed and when millions of Jews were imprisoned, gassed, and incinerated behind the barbed wire perimeters of Nazi death camps. As I glanced back to make sure he wasn’t following, I noticed three words painted in English on a metal door that rusted nearby: GAS THE ARABS.

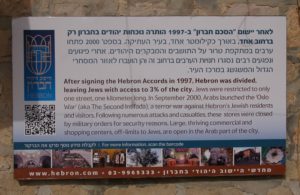

This sign posted in Hebron explains why Palestinian shops on Shohada Street were closed: To protect Jewish lives. (Photo: Dexter Van Zile)

The implication is clear. Israeli Jews living in Hebron are doing, or planning on doing the same things to the Palestinians that was done to their relatives living in Europe. This is a cheap and easy libel. Shops are closed on Shohada Street not because the Israeli government wants to steal Palestinian property — the way property was confiscated from Jews during the Holocaust — but because Israel has decided that Jews should be able to walk freely in at least one street in a city that has had a Jewish presence for most of its 3,500 year history.

Fisk is right to be outraged by the anti-Arab graffiti that Jewish leaders in Hebron have tried to cover over with spray-paint. But predictably enough, Fisk simply does not exhibit the same level of outrage toward antisemitic incitement in Palestinian society, much of which is broadcast on TV stations run by Hamas and the Palestinian Authority.

Conclusion

Maybe Bruce Fisk has done the world a favor. He has unwittingly exposed the template that Christian peacemakers use in framing the Israel-Palestinian conflict they say they want to help bring to an end.

In this anti-historical and demonizing frame, modern-day Jews are an amalgam of the evil Romans and corrupt Jewish leaders who conspired to murder Jesus in First Century Jerusalem. The Palestinians are marginal and innocent first century Jews living under Roman occupation. Israeli peace activists (whose credibility was destroyed by Arafat’s refusal to make peace when he had the chance) are stand-ins for Jesus who weeps over the inability of those stiff-necked Jews in Jerusalem to know and do the things that make for peace.

Anyone who applies this frame to the Israel-Palestinian conflict is not a peacemaker, or even a hitchhiker, but a sleepwalker through the Holy Land.