- 1.6K

- 1.7KSHARES

Sept. 18 Update:

CAMERA Prompts New York Times Correction on Judaism's Holiest Site

In response to CAMERA's Sept. 13 correspondence with Times editors, a print correction appears in today's print edition. See below for a detailed update.

The New York Times architecture critic seems to have a problem with Jerusalem, the holiest city in Judaism.

In a Sept. 13 article, the Times critic, Michael Kimmelman, took aim at a planned line of cable cars that the Jerusalem municipality hopes will soon shuttle visitors toward the Old City’s archaeological and touristic center.

But the cable car, which some worry will be an eyesore in the ancient city, isn’t the real problem in Kimmelman’s article. It’s just the hook. The deeper problem relates to Jews, and the value they place on their rich history.

A replica of Michelangelo's David in Florence attests to the centrality of Jerusalem's Jewish heritage throughout the world.

Kimmelman endorses concerns that the Jews who run the city will turn Jerusalem from a “global heritage site“ into a “Jewish-themed Epcot.” A few paragraphs later, he laments the possibility that the cable car plan “curates a specifically Jewish narrative of Jerusalem.” Later still, he protests that future riders might be “funneled through a Jewish version of the city’s history.” And finally, he relays criticism about efforts “to inculcate a Jewish narrative of occupied Jerusalem.”

It may be that Jewish historians and archaeologists are less capable of clearheaded scholarship than non-Jewish ones. But otherwise, the “Jewish version” of history could be better described as, well, “history.”

In the case of Jerusalem, it just so happens that the period of history that excites Jews most is also the period that has long captured the attention and imagination of the rest of the world: The Jerusalem of the Bible, of King David, of the holy temples, of the Maccabees, of Herod, and of Jesus.

It is true, too, that Selijuks and Khwarezmids and Ayyubids, invaders from elsewhere in the Middle East, each took a turn ruling over the city during the Middle Ages. This is also real history. But they are to Jerusalem what Cola di Rienzo and Clement V are to Rome: Rulers, but not Caesars. Historical, but not historic.

For Kimmelman, though, the opposite is true. Unlike the “Epcot” or “Disneyfied” Jewish narrative he disdains, it is everyone else’s Jerusalem that is most authentic. A critic is entitled to his preferences. But consider how his opening paragraph erases Jews from the archaeological history of the Old City:

At a glance, Jerusalem’s Old City and its surroundings still look pretty much as they must have looked centuries ago. The Old City’s yellow walls still read in silhouette against an ancient landscape of parched hills and valleys. The skyline is still dominated by the city’s great Muslim and Christian shrines: the gold, glistening Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, where Jesus was said to have been buried.

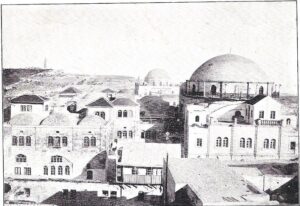

Missing from Kimmelman’s flashback are the Hurva and Tiferet Israel synagogues, great domed structures that that held proud spots on the Jerusalem skyline from the mid-1800s until they were destroyed by the conquering Jordanian army in 1948.

It is a convenient omission, as later in the piece Kimmelman unfavorably compares today’s municipality with the city’s two prior colonial rulers, whom he casts as protectors of the city’s heritage. “Modern Jerusalem was spared Disneyfication,” he writes, “first by the highborn culture of British colonialism, with its awe for the city’s antique past, and next by Jordanian paralysis, which froze the Old City as if in amber.”

From someone who purports to care deeply about architectural and demographic preservation, this assertion is striking. The destruction of the Hurva synagogue was hardly an act of preservation. “This affair will rankle for generations in the heart of world Jewry,” a British official said after Jordanians reduced the synagogue to rubble. (That the destruction was seen as an affront to Jews might help explain why Kimmelman, averse to the "Jewish version" of history, ignores the architectural crime.)

The prominent domes of the Hurva and Tiferet Israel synagogues.

Far worse than the destruction of buildings, however grand, was how the Jordanian conquerors changed the social fabric of the Old City: by expelling every last Jew. So much for amber.

Kimmelman’s instinctive recoiling from Jewish works in the city is exemplified by two contrasting paragraphs in his piece. On the one hand, he protests the construction of tall glass buildings in what is, after all, Israel’s largest city by both population and area:

In a city long defined by low-rise, stone-clad buildings, Israeli authorities are now approving 40-story glass towers and cut-and-paste office park development more in keeping with Singapore or Jakarta than Jerusalem.

But only four paragraphs later, those stone-clad structures he favorably mentioned become a problem:

Even the cladding of East Jerusalem’s settlements in Jerusalem stone, the architectural uniform traditionally worn by buildings in Jewish West Jerusalem, helps spread the image of a single Jewish city.

The long tradition of using Jerusalem stone was formalized into law by the British authorities, motivated by that “awe for the city’s antique past” Kimmelman praises. It is only when Israel inherited the British ordinance that the stone cladding became evidence not of awe, but of a propaganda campaign. For the Times architecture critic, then, the buildings matter less than who is doing the building.

If glass is a problem, and stone is a problem, what then does the Times journalist think is appropriate for Jews in Jerusalem?

Kimmelman seems to find his answer at the Western Wall, which he wrongly identifies as the holiest site in Judaism. (That distinction belongs to the Temple Mount. CAMERA has discussed the error with editors and requested a correction.)

To close the article, he quotes a critic of the cable car project who makes sweeping and controversial statements about no less than the essence of Judaism:

The Western Wall is “a ruin, humble, an ancient site of sadness and loss,” [one architect] says. “It is the true heart of Judaism. The cable car is the opposite, flashy, vulgar and aggressive.”

The New York Times message, then, is that true Judaism doesn’t thrive in Jerusalem. It doesn’t recover from exclusionary, anti-Jewish policies by imperial powers, and doesn’t regain a rightful spot on the ancient skyline. It doesn’t build with stone to accommodate Jews returning to the section of the city ethnically cleansed by Jordan, and doesn’t build with glass in the mold of thriving, modern capital cities. True Judaism is only powerlessness, ruins, and mourning.

This narrow and anachronistic version of Judaism, one influenced by anti-Zionist thought that was thoroughly discredited after the Holocaust, might be the version long preferred by New York Times publishers. But it’s not what most Jews in Jerusalem and beyond accept today. It is that fact, more than any cable cars, that seems to bother Kimmelman.

Sept. 18 Update: CAMERA Prompts New York Times Correction

In response to CAMERA's Sept. 13 communication with Times editors regarding Kimmelman's erroneous claim that the Western Wall is Judaism's holiest site, the following correction appears in today's print edition:

An article on Sunday about a planned cable-car network to Jewish holy sites erroneously attributed a distinction to the Western Wall in Jerusalem. It is one of the holiest sites in Judaism, not the holiest.

In addition, editors corrected the online article Sept. 16. Unfortunately, the corrections fail to make clear that the Temple Mount holds that distinction.