In an enthusiastic Los Angeles Times review of The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey, Carol J. Williams, together with the cookbook authors Laila Haddad and Maggie Schmitt, take the opportunity to brew up a number of false charges against Israel (“For Gaza cooks, it’s two parts rice, one part defiance“). In the introduction to her interview with Haddad and Schmitt, Williams writes:

Israeli troops have imposed a tight cordon around Gaza border crossings, sea access and airspace since the strip’s 2007 takeover by the militant Islamic group Hamas, crippling a fragile economy where nearly half the residents are jobless.

That means Gazans are confronted with daily challenges to put their signature foods on the family table: Locally made olive oil has disappeared, the once-resplendent olive groves blasted by artillery exchanges. The deep channel of migrating fish off the Mediterranean shore is now off limits. Even the red tahina that reflected Gazans’ unique way of toasting sesame seeds has faded into memory for many, a victim of import controls.

Food Restrictions Lifted in June 2010

First, there is absolutely no restriction on the import of tahina, or any other food, since June 2010. As the Los Angeles Times’ own Edmund Sanders reported on Oct. 18, 2012:

Under international pressure, Israel ended the restrictions on food in 2010, though it continues to ban commercial exports and imports of goods such as cement or other items Israel says could be used to build military bunkers or weapons.

Indeed, Williams’ introduction stating that Israel’s “tight cordon” supposedly causes daily hardships for Gazans’ meals is entirely false given that all food restrictions have been lifted since June 2010. Williams’ distorted narrative also ignores the fact that Israel does not have sole control over Gaza’s border crossings. In fact, Egypt shares the Rafah border with Gaza, and imposes its own blockade on the territory.

More, Not Less, Olive Trees

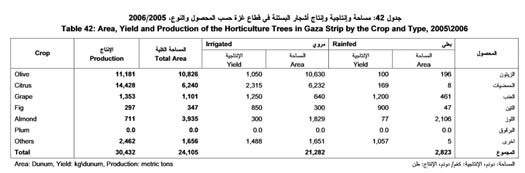

Is it true that, since the Hamas takeover in 2007, artillery exchanges decimated the Gaza Strip’s olive groves? Not according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, whose figures show there are signficantly more olive trees now than in the years before Israel imposed a blockade on the Gaza Strip. Table 42 from the PCBS’ Tree Horticulture Survey, 2006 reveals that from October 2005 through September 2006 (which is how the PCBS defines an agricultural year), or before the Israeli blockade, the Gaza Strip’s olive trees covered 10,826 dunums and produced 11,181 metric tons of fruit.

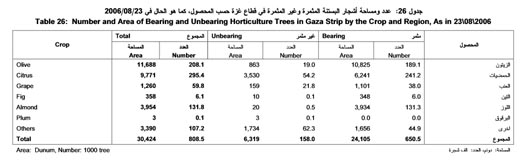

In addition, Table 26 of the same report shows that, also before the Israeli blockade, the PCBS found that as of Aug. 23, 2006, there were 208,100 olive trees in the Gaza Strip.

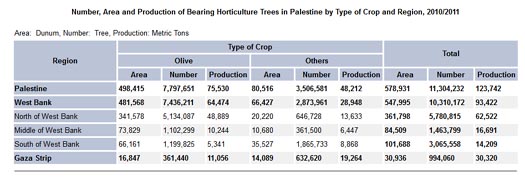

In comparison, following a few years of the Israeli blockade, PCBS reported that in the agricultural year of 2010-11, there were 361,440 olive trees in the Gaza Strip. In other words, from 2006 (before the blockade) to 2010-11 (three years after the blockade), the number of olive trees in the Gaza Strip increased dramatically. It’s true that fruit production was slightly down, but olive crops fluctuate from year to year.

Locally-Made Oil Increases, Not ‘Disappeared’

And what about the locally-made olive oil, which Williams contends has “disappeared”? Here, too, figures from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics show the opposite to be the case — there were more presses extracting more oil after the Israeli blockade versus before the blockade. According to the PCBS Olive Presses Survey 2006, there were 15 olive presses in the Gaza Strip, all of them operational. By 2010, there were 17 olive presses in the Gaza Strip, 16 of them operational, and one was temporarily closed (PCBS Olive Presses Survey 2010, Table 2). In 2006, those 15 presses extracted 1,731.1 metric tons of oil. By 2010, that figure increased to 1,839.2 metrics tons (Table 4 in the respective surveys).

A Palestinian man checks the quality and colour of olive oil being freshly pressed from local olives in Gaza City, in the Gaza Strip on November 12, 2011. photo by Wissam Nassar(Credit Image: Wissam Nassar Apaimages/APA Images/ZUMAPRESS.com)

A Palestinian worker displayed olive at an olive press in Gaza City October 16, 2012, Yousef Deeb/Wostok Press

Tahina Consumption Also Up

In another false claim of culinary hardship,Williams claim that even “the red tahina that reflected Gazans’ unique way of toasting sesame seeds has faded into memory for many, a victims of import controls.”

Tahina consumption was greater in 2010, the first half of which some food restrictions still applied, than it was in 2005, before the blockade. According to the PCBS Household a

nd Expenditure and Consumption Survey 2005 (Table 11), the average household in the Gaza Strip (7.5 people) consumed 0.348 kilos of tahina in 2005 per month. In 2010, the PCBS (Expenditure and Consumption Survey, 2010, Table 3.1), found that the average Gaza household (6.6 people) consumed 0.386 kilos of tahina per month. In other words, the average Gaza household of 2010 was smaller than the 2005 average household, and yet it consumed more tahina.

Semolina Holding Steady

The story is pretty much the same for semolina. Haddad, one of the cookbook authors, alleges:

You don’t find people using semolina in their baked goods anymore. The traditional cookies of Gaza are made of semolina, olive oil and date paste. Most people now substitute white flour, soybean oil and white sugar — stuff you get in the aid distribution.

In fact, the semolina situation is not quite so dire. According to PCBS, the average family household of 7.5 in Gaza consumed .484 kilos of semolina in 2005. In 2010, the average family household was slightly smaller, with 6.6 individuals, and it consumed .458 kilos of semolina per month, only slightly less than the 2005 household of 7.5 people.

Williams terms The Gaza Kitchen “a salute to both Palestinians’ cuisine and their spirit of resistance.” That may be. But Williams’ interview with the two women is not the solid analytical review one would expect from a journalist with 25 years of experience in foreign affairs. It is a journalistic travesty which the Los Angeles Times must now correct on numerous points.