- 1.8K

- 1.8KSHARES

Earlier this month, NPR’s Michele Kelemen told her audience that Palestinian-Israeli peace talks failed in 2008 when Israel’s prime minster was indicted for bribery. It is true that peace talks fell apart in 2008, but the demise of the talks couldn’t have been a consequence of Olmert’s indictment, which only happened a year later, in 2009.

Kelemen’s chronological shuffle is an example, though a subtle one, of a widespread journalistic phenomenon: the erasure of Palestinian rejections of peace offers, or even of the existence of the offers themselves.

The history rejected peace offers, including Israel’s offer in 2008, is an inconvenient truth for those who prefer the narrative that Israel alone is to blame for the continuation of the Arab-Israeli conflict. After all, if Palestinians leaders have repeatedly turned their backs on peace treaties that would give them a state, what does it say about the often-heard claim that those leaders seek only freedom, self-determination, and statehood for their people?

It’s a question better avoided by those who prefer to view Palestinians as lacking any agency. And so those peace rejections have become the Big Omission of Western reporting on the conflict, meant to protect the peace rejectionists who’ve needlessly prolonged the conflict.

New York Times reporter Mark Landler served up a sublime example of the Big Omission last April when he summarized the failed history of peacemaking as follows:

[W]hat peacemakers have tried to do is figure out if there’s a way to create a separate homeland, a separate state for the Palestinians, one where they would manage their own affairs, enjoy the benefits of self-rule, but live in peace with their neighbors, the Israelis.

This task became more and more difficult over the years because through wars and other conquests, the Israelis began to occupy more and more of the land that would form the basis for a Palestinian state.

This is disingenuous pseudo-history. But in order to hold Israel entirely responsible for the lack of a Palestinian state, reporters must ignore (among so many other things) the fact that Palestinians have repeatedly turned down plans that would have given them that state, as Landler so glaringly does above.

The recent NPR example was, as noted, a more subtle variation of the Big Omission. In Kelemen’s framing, talks between former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Palestinian Authority head Mahmoud Abbas “failed in 2008 after Olmert was indicted for bribery and forced to resign.”

The issue isn’t narrowly that the indictment and resignation came after the event they supposedly precipitated. Olmert was, after all, consistently beset by corruption investigations, which took place before, during and after his talks with Abbas. There was already talk of resignation in the weeks and months prior to his comprehensive peace offer in 2008.

The greater problem is that, by pointing the finger at Olmert’s indictment, NPR manages to avoid acknowledging Abbas’s paramount role in the breakdown of talks. He rejected Olmert’s offer, which effectively ended hopes for peace.

In early May of 2008, Olmert said he would resign if indicted. In July of that year he went further, announcing that once his Kadima party picked a new leader, he would step down. And in early September, Israel’s police recommended an indictment. The whole while, though, Olmert and Abbas met repeatedly for talks to resolve the conflict.

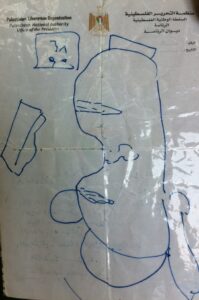

The negotiations culminated on September 16, 2008 with Olmert’s far-reaching offer to his Palestinian partner, which included a Palestinian state on the Gaza Strip, about 94 percent of the West Bank, and additional Israeli territory to compensate for the the West Bank land Israel would retain. A map later drawn by Abbas (which looks strangely like a sketch of SpongeBob throwing a brick at Mr. Potatohead) memorialized the offer on Palestinian Authority letterhead.

Abbas said he would think about it and promised to resume the conversation the next day. “But the next day Saeb Erekat rang my adviser and said we forgot we are going to Amman today, let’s make it next week,” Olmert later recounted. “I never saw him again.”

The takeaway was clear. “Abbas turned it down,” the Washington Post’s Jackson Diehl reported after interviewing the Palestinian leader in 2009. “The gaps were wide,” Abbas told the columnist.

“I didn’t accept it,” Abbas later reiterated during an interview with Israel’s Channel 10. “No way did I accept it.”

Olmert was stunned. “To this day, I cannot understand why the Palestinian leadership did not accept the far-reaching and unprecedented proposal I offered them,” he lamented.

In her memoir, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice described Olmert’s “remarkable” concessions, and stated that “a Palestinian president accepting them would have pushed the peace process to a new level.” Alas, “Abbas refused,” Rice wrote.

It was effectively the end of the conversation. As the secretary of state put it, a final American push to revive Olmert’s ideas failed:

We had one last chance. The two leaders came separately in November and December to say good-bye. The President took Abbas into the Oval Office alone and appealed to him to reconsider. The Palestinian stood firm, and the idea died.

Many years later, the Associated Press summarized the events of 2008 by stating that Abbas “rejected an offer from Israel’s Ehud Olmert.”

Ironically, the Associated Press was the first to give Olmert’s offer the Big Omission treatment. Matti Friedman, who worked as an AP reporter and editor from 2006 to 2011, wrote in Tablet of how AP editors at his Jerusalem bureau spiked the story:

In early 2009, for example, two colleagues of mine obtained information that Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert had made a significant peace offer to the Palestinian Authority several months earlier, and that the Palestinians had deemed it insufficient. This had not been reported yet and it was—or should have been—one of the biggest stories of the year. The reporters obtained confirmation from both sides and one even saw a map, but the top editors at the bureau decided that they would not publish the story.

Some staffers were furious, but it didn’t help. Our narrative was that the Palestinians were moderate and the Israelis recalcitrant and increasingly extreme. Reporting the Olmert offer—like delving too deeply into the subject of Hamas—would make that narrative look like nonsense. And so we were instructed to ignore it, and did, for more than a year and a half.

The reporter responsible for bringing the story to editors, Mark Lavie, was inspired by his colleague’s exposé to discuss the cover-up that, he said, was “by far the worst journalistic fiasco I have been involved in”:

The AP suppressed a world-changing story for no acceptable reason. I am not ascribing motives to the decision — oh, hell, of course I am. It fit a pattern, described by Matti, of accepting the Palestinian narrative as truth and branding the Israelis as oppressors.

The impulse that led the AP to shred so important a story is the same one that has inspired amnesia in countless pundits who try to market the conflict as a morality play in which Israel, the antagonist, denies freedom to eager Palestinians.

And it is the same impulse that produced NPR’s backward chronology, which placed Olmert’s 2009 indictment before, and as the cause of, the breakdown of talks a year earlier. It is the Big Omission, and a big breach of NPR’s promises to news consumers.