- 376

- 382SHARES

In a gushing review of The Daily, a New York Times podcast broadcast every weekday morning featuring interviews with the newspaper’s reporters, a staff writer for the New Yorker praised the program for offering “not just facts but feels.”

Whatever the reviewer might have meant by this, it’s clear that the feelings of Times journalists on The Daily do, often, supersede the facts, leaving the program’s many listeners on the receiving end of facts and feels, perhaps, but also misrepresentations and falsehoods.

Consider the pair of segments broadcast after the Israeli elections, in which Michael Barbaro, host of The Daily, interviewed a Times reporter (on April 11) and a Palestinian anti-Israel activist (on April 12).

During the April 11 episode, listeners heard from Barbaro and his colleague Mark Landler, a New York Times White House correspondent, as they contextualized Benjamin Netanyahu’s election victory with a bizarre account of Israeli and Palestinian history.

An “Occupied” Israel

To make the case that the two-state solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is “dead” — this is apparently one of those “feels” that The Daily offers — Landler told listeners,

The dilemma that has faced Israel since its founding in the 1940s was that the land that the Israelis occupied, the ancestral homeland for the Jewish people, was land that was actually also claimed by the Palestinians.

The reporter’s use of the word “occupy” to describe Israel’s existence in the Middle East since the 1940s might raise eyebrows. Surely Landler knows that the occupation, the focus of endless criticism of Israel in his newspaper, began only in 1967. To apply that loaded word to pre-1967 Israel, then, might suggest a lack of validity to the country’s very existence.

But let’s give the reporter the benefit of the doubt. In an extemporaneous chat, there isn’t always the luxury of weighing every word. Still, the rest of Landler’s discussion of Israel’s history leaves little doubt about his lopsided take on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A Revisionist History of Palestinian Statelessness

As noted above, Landler explained that Israel was created on land “also claimed by the Palestinians.” So, he continued, “what peacemakers have tried to do is figure out if there’s a way to create a separate homeland, a separate state for the Palestinians, one where they would manage their own affairs, enjoy the benefits of self-rule, but live in peace with their neighbors, the Israelis.”

Why didn’t that happen? Landler points to only one culprit: “This task became more and more difficult over the years,” he said, “because through wars and other conquests, the Israelis began to occupy more and more of the land that would form the basis for a Palestinian state.”

This summary of Palestinian statelessness isn’t just simplistic. It obfuscates to the point of being ahistorical. Even before Israel existed, peacemakers had worked out how to create a homeland for the Palestinians. When the United Nations first called for a Jewish state in part of British-ruled Palestine in 1940s it also drew the contours of an Arab state in the remainder of the land.

This summary of Palestinian statelessness isn’t just simplistic. It obfuscates to the point of being ahistorical. Even before Israel existed, peacemakers had worked out how to create a homeland for the Palestinians. When the United Nations first called for a Jewish state in part of British-ruled Palestine in 1940s it also drew the contours of an Arab state in the remainder of the land.

The problem, then, wasn’t that diplomats hadn’t “figured out” how to create a Palestinian homeland, as Landler argued. The problem was that, while the Jews accepted the UN partition plan, Palestinian leaders and the rest of the Arab world rejected any compromise that would have delivered a Palestinian state alongside a Jewish one.

The New York Times’ own coverage in 1947 of the UN compromise decision reported thoroughly on the Palestinian rejection of the plan. One article quoted a Jewish leader who reached out to the anticipated Arab state:

We pray for the peace of Palestine. We extend a hand of genuine friendship to the new Arab state which is to be established in Palestine. The Jewish nation in Palestine will be eager to cooperate fully with its Arab neighbor….

On the other hand, the same article noted, “there was an open thread of warning running through all the Arab delegates’ comments” about the decision. They spoke of “bloodshed to come.”

Arab leaders threatened “dire consequences” and a “crusade against the Jews” if the UN didn’t reverse its decision, and they followed through, resorting to deadly violence against the area’s Jewish population. “In a violent Arab retort to the United Nations decision on Palestine seven Jews were killed by Arab ambushes in Palestine today,” the 1947 version of the New York Times reported.

Why, then, does the 2019 version of the paper want its audience to believe that Palestinian leaders were open to “living in peace with their neighbors, the Israelis,” even though that was demonstrably untrue in the 1940s and remained untrue for decades to come?

Rather than accept the compromise plan offered by peacemakers, Palestinians, Egyptians, Jordanians, Syrians and other armies from the Arab world joined together in a war to destroy the new Jewish state.

They failed. But even then, the Palestinians could have had a state in the parts of British Palestine that didn’t become Israel after the war, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Instead, for the next two decades, Egypt remained in the Gaza Strip while Jordan kept control of the West Bank, annexing it in a move rejected by the international community. The whole while, Palestinian and other Arab leaders remained committed not to a Palestinian state living in peace alongside Israel, but rather to the destruction of the Jewish state.

In their 1964 “Palestine National Charter,” for example, Palestinian leaders reiterated their rejection of the UN partition plan, called for the elimination of Israel, and even denied all historical ties between Jews and their ancestral homeland. In the Charter, Palestinians also sanctioned Jordanian and Egyptian control over the West Bank and Gaza Strip by disavowing Palestinian sovereignty in those areas.

There is no room for any of this in Landler’s history, which would have listeners believe that Israeli belligerence, and nothing else, impeded a Palestinian state. No Palestinian rejection of the UN statehood plan. No Arab occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. No commitment to the destruction of Israel. Just Israeli “wars and other conquests” — Landler’s way of describing the 1967 Six-Day War, which, contrary to The Daily’s insinuation of a war of Israeli aggression, was precipitated by Egypt and its Arab neighbors.

Also ignored was the continued Palestinian rejection of “peace with their neighbors, the Israelis” for another couple of decades after the 1967 war. And their leaders’ rejection of multiple peace offers, including in the 2000s, that would have created an independent Palestinian state.

To conceal all of this in a telling of why no Palestinian state exists today is neither history nor journalism. It is a crude anti-Israel narrative — a rewrite of the past that places blame only on Israel while completely exculpating other parties to the conflict. It is, unfortunately, consistent with how the newspaper has recently tended to report on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A Falsehood on the 1967 Occupation

As Michael Barbaro and Mark Landler continued their conversation, they also continued to mislead their audience. Here is how they characterize the 1967 war:

Barbaro: And Mark, just so I understand, why does the U.S. feel strongly about a two-state solution, and why does it care about it?

Landler: I think for a couple of reasons. One is a legal reason. Israel took the land in the West Bank by force in the Arab-Israeli War of 1967. This move was condemned widely by the United Nations, by other countries, and even by the United States as an unlawful seizure or conquest of territory.

It is not true, though, that the US, or even the UN, characterized Israel’s capture of the West Bank after being attacked from that territory in 1967 as “unlawful.”

In fact, the US supported continued Israeli control the West Bank until its neighbors agreed to peace terms. According to the State Department’s Office of the Historian, Lyndon B. Johnson, the American president at the time, “did not want to try to pressure the Israelis into withdrawing from the captured territories.”

Yes, the administration wanted Israel to eventually withdraw from much of the West Bank, but not unilaterally. “There are some who have urged, as a single, simple solution, an immediate return to the situation as it was on June 4,” the day before the 1967 war broke out, President Johnson said in a major address after the war. He countered, “This is not a prescription for peace but for renewed hostilities.”

Johnson believed an Israel withdrawal should come only alongside a durable peace that includes Arab recognition of Israel’s right to exist. Needless to say, the president’s policy-setting address said nothing about the capture of the West Bank being “unlawful.”

The UN, like the United States, made clear that any Israeli annexation of the West Bank would be “inadmissible,” but none of its post-war resolutions — General Assembly resolutions 2252, 2253, 2254, and 2256, and Security Council resolutions 236, 240, and 242 — argued that the seizure of the West Bank from Jordanian was “unlawful.”

The drafters of Security Council Resolution 242, which called for an Israeli withdrawal from unnamed “territories occupied in the recent conflict,” repeatedly clarified that their resolution calls for any Israeli withdrawal to be to “secure and recognized boundaries” negotiated in peace talks between the parties to the war. “Until that condition is met, Israel is entitled to administer the territories it captured – the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza Strip – and then withdraw from some but not necessarily all of the land,” explained Eugene Rostow, one of the resolution’s drafters and an Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs in President Johnson’s administration.

Did Netanyahu Turn Israelis from 2-State Solution by Building a Wall?

Landler’s conversation about the supposed illegality of Israel’s capture of West Bank from Jordan was not the last of the “feels” disguised as fact in the April 11 segment.

When Barbaro asked his guest how Israel responded to the “decades-long push from the U.S. and the rest of the world for a two-state solution,” Landler delivered a surreal account of why many Israelis became less enthusiastic about that political path:

Barbaro: And how does Israel respond to this decades-long push from the U.S. and the rest of the world for a two-state solution?

Landler: Well, it depends very much on who’s in government, but the general trend line in Israel is that early in this process, many Israelis felt that the two-state solution was the only solution to their problem. There was a great deal of sympathy and support in Israel for a two-state solution, not just on the Israeli left, but on the right. But then Benjamin Netanyahu is elected prime minister, and Netanyahu sets in motion a series of programs and policies that have the effect of hardening Israeli attitudes against the desirability of a two-state solution. He really builds up the Israeli economy. He makes Israel a powerhouse in the region. He builds up Israel’s military. He makes Israelis feel, for the first time, more secure. He builds a wall between Israel and the West Bank. So he literally walls off Israelis from the problem of the Palestinians.

“How does Israel respond to the decades-long push … for a two-state solution?” The most straightforward answer is that Israel offered Palestinians that very solution — peace and statehood alongside Israel — in 2000 and in 2008. But Landler says nothing of those offers, which subsequent Palestinian leaders rejected.

Instead, we again see how New York Times journalists believe, or want their audience to believe, that Palestinians play no role in the ongoing conflict. Israeli support for the two-state solution diminished, we’re told, and it’s basically Netanyahu’s fault the fault of the “wall” he purportedly built.

Note, as an aside, that Landler opted to describe the security barrier as a “wall,” although the New York Times itself has acknowledged that the word is a Palestinian weapon in the linguistic skirmish between the sides when they use it to describe a barrier that is, actually, overwhelmingly a fence. Note also the reporter’s euphemism — Netanyahu “literally walls of Israelis from the problem of the Palestinians” — that suggests the barrier is an act of Israeli racism and conceals that it was, in actuality, the country’s response to a deadly wave of Palestinian suicide bombings on civilian buses, cafes, and dance clubs.

But it’s not just Landler’s euphemism that misleads. Did Netanyahu build the barrier, as the reporter claimed?

In fact, most of the barrier was built by the late Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. And when Netanyahu came to power in March 2009, the construction ground to a near halt. “In 2009, work on the Separation Barrier slowed appreciably,” B’tselem reported. “According to figures of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), only four kilometers were added in 2009. Of the planned 709 kilometers, 413 kilometers have been completed (58 percent).”

And in the decade that followed, the construction was “mostly frozen,” explained Israeli journalist Tovah Lazaroff. B’tselem and the United Nations assessed that “as of September 2017 some 460 kilometers (about 65% of the planned barrier) had been completed” — which means Netanyahu has hardly nudged the barrier project forward, and so can hardly be held responsible for building a wall that has supposedly weakened Israeli support for the two-state solution.

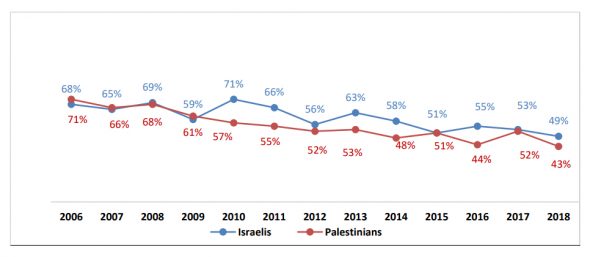

And while it is true that there has been a general downtrend in Israeli and Palestinian support for two-states over the past decade, it is absurd for the Times to cast Netanyahu and his policies as the root cause of that trend.

According to one poll, there was an increase in Israeli support for a two-state solution after Netanyahu’s first few years in office.

Another poll found that support for two-states dramatically shot up the year he took office, from 59 percent to 71 percent. The researchers behind this poll argued that the subsequent downtrend in support for a two-state solution was driven in part by mutual distrust of the other side’s beliefs and intentions.

Israeli analyst Shmuel Rosner, a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, cited similar sentiment when describing the decline of the two-state option:

Israel’s trust-the-Palestinians camp lost the argument after the 2000 Camp David summit failed and was followed by a bloody Palestinian uprising, the second Intifada. Israel’s unilateral-withdrawal camp lost the argument following the 2005 “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip, which resulted in nearly constant conflict on the Israel-Gaza border. Even many Israelis who believe that the Palestinians deserve a state find it difficult to believe that Palestinian leaders and institutions can be trusted with one.

After Netanyahu took power in 2009, there were more reasons for Israelis to grow wary of Palestinian leaders: A decision by Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas to avoid peace negotiations with Netanyahu and to instead unilaterally pursue international recognition of a Palestinian state. A pair of “unhinged” speeches by Abbas that included anti-Semitic slurs and wild conspiracy theories, which prompted Barack Obama’s ambassador to Israel to conclude that the Palestinian leader was “out of the peace talks game.” A wave of Palestinian stabbing attacks. A wave of Palestinian car ramming attacks. A war with Hamas, the Palestinian group that rules the Gaza Strip. The rise of Palestinian cross-border tunnel attacks from Gaza. Might these have influenced Israelis feelings about whether they should evacuate the West Bank? Not according to Times reporters, who seemingly can only find fault with one side.

Jerusalem Embassy “Feels”

When the Times journalists turned their attention to the American decision to move the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, Landler claimed that American officials did not, in doing so, “make the point that they still view East Jerusalem as a potential Palestinian capital.”

The Americans “seem to say it’s not the capital of the future Palestinian state,” Barbaro responded.

Yes, echoed Landler, “it would seem to foreclose the possibility of having East Jerusalem be the Palestinian capital.”

The repeated use of the word “seem” signals, again, the triumph of feels over facts. Because it is simply untrue that the embassy move forecloses the possibility of Palestinian capital in east Jerusalem. “The move will not … prevent a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem or change the fact that the two parties will need to negotiate the status of Jerusalem as part of resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” PBS Newshour paraphrased former State Department official Tamara Wittes as saying.

Daniel Shapiro, President Obama’s former ambassador to Israel, likewise argued in the Washington Post that “nothing about our embassy’s location there [in Jerusalem] would prevent the emergence of a shared city with two capitals as part of a two-state solution.

And the American president himself made clear that, with the embassy move, “We are not taking a position on any final status issues, including the specific boundaries of the Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem or the resolution of contested borders.” Official American maps of Israel repeat that language, noting that “The United States recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2017 without taking a position on the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty.”

And the American president himself made clear that, with the embassy move, “We are not taking a position on any final status issues, including the specific boundaries of the Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem or the resolution of contested borders.” Official American maps of Israel repeat that language, noting that “The United States recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2017 without taking a position on the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty.”

Contrary to the claims of the Times journalists, then, the Americans did leave open the possibility of East Jerusalem as a future Palestinian capital.

Another Day, Another Dose of Anti-Israel Election Coverage

The next day, The Daily again dealt with Israel’s election. But if the audience was expecting a segment that that might balance the previous day’s blame-Israel narrative — perhaps by incorporating Israeli voices? — they instead heard another lopsided program, entitled “Israel’s Election, Through the Eyes of a Young Palestinian.”

The interview with the Palestinian anti-Israel activist, Fadi Quran, largely reiterated the points made a day earlier by Landler, who ignored the Palestinian rejection of peace offers while blaming Israel alone for the lack of a Palestinian state.

Quran, for example, blames Israelis for the Palestinian wave of violence that killed a thousand Israelis, mostly civilians. During peace talks between Israelis and Palestinians, he said, “more and more of our land, more and more of what we considered to be Palestine was just going to be eaten away by these kind of settlers.” (If that sounds familiar, it is because Landler offered the same narrative, with virtually the same words, one day earlier: “The Israelis began to occupy more and more of the land that would form the basis for a Palestinian state.”)

“They’re never going to give us our freedom,” Quran continued. “It was like, enough is enough.”

Here, to punctuate the narrative that Israeli repression is to blame for Palestinian violence, Barbaro inserted an archival recording of a news report describing a suicide bombing “that ripped through two buses.”

“This is the intifada,” said Barbaro.

“This is the intifada,” said Quran.

But neither offered a hint that the Palestinian violence of this intifada came after Yasir Arafat, the Palestinian president, rejected a peace offer that would have removed settlers and created a state of Palestine.

Instead, Barbaro played a misleading sound-bite that characterized the Palestinian violence as having targeting only Israel’s military: “The protests evolved from boys throwing rocks and people marching to fighters attacking Israeli soldiers and military targets.”

The clip, from Al Jazeera, egregiously misinforms listeners. The fighters it described certainly targeted and killed Israeli civilians. But a bigger deception here comes from the New York Times and Barbaro, who chose this sound-bite, about the so-called first intifada, to illustrate a conversation about the even deadlier second intifada that began more than a decade after the first.

Why the anachronistic audio clip? Was Barbaro, whose segments about the Israeli elections downplayed any Palestinian responsibility for their conflict, unable to resist a clip that essentially denied Palestinian attacks on Israeli civilians?

In the first-ever episode of The Daily, Barbaro explained the purpose of his show to listeners: “We’re here because this moment demands an explanation.” But it is listeners who now deserve an explanation.

Why pretend Palestinians didn’t attack civilian targets in their intifada? Why, in a conversation about the lack of a Palestinian state, hide the Palestinian rejection of peace and statehood in 1947, and 2000, and 2008? Why ignore any Palestinian role in shaping Israeli opinion about a two-state solution? Why say Netanyahu is to blame for building a security barrier to which he scarcely contributed?

Why call that barrier, mostly fence, a wall? Why say Israelis “occupied” the country in the 1940s? Why misstate the American position on Israel’s capture of the West Bank in 1967? Why insist that a U.S. embassy in Jerusalem somehow prevents the option of a Palestinian capital in part of that city?

Sadly, it seems anti-Israel advocacy journalism has become the norm at the New York Times, whether in print or over the airwaves.