- 691

- 698SHARES

The New York Times misinformed readers in two recent stories about Palestinians in the Jordan Valley — and although the newspaper promises to correct mistakes big and small, it has yet to correct its errors.

Access to Jordan Valley Land

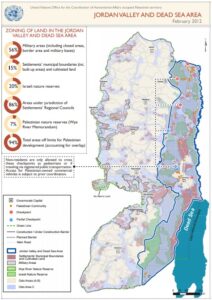

In the first story, a Sept. 10 piece by Ben Hubbard, the paper erred about Palestinian access to the Jordan Valley, a stretch of land parallel to the Jordan River that runs along the West Bank’s eastern border. Citing the Israeli advocacy group B’Tselem, Hubbard told readers Palestinians are “barred from entering or using about 85 percent” of the Jordan Valley where it passes through the West Bank.

The claim that Palestinians are only able to enter 15 percent of the territory, though, is false.Depending on where exactly one draws the boundaries of the Jordan Valley — there’s no single, official delineation of the territory — between seven and thirteen percent of the region is designated as Area A or Area B — the names given to West Bank territory in which civilian matters are administered by the Palestinian Authority, in line with peace agreements signed by Israel and the Palestinians.

Israeli communities and their lands, which sit within Area C, the third and largest portion of the West Bank, take up another roughly eight to fifteen percent of the Jordan Valley. The New York Times itself has frequently documented that Palestinians can enter these settlements. Indeed, on the very day Ben Hubbard’s piece was published, a separate Times story noted that that nearly all the male population of Fasayil, a Palestinian village in the Jordan Valley, are employed in the neighboring settlement of Tomer. Even if these agricultural workers needed to obtain security clearances from Israeli authorities, their daily presence in Tomer — along with the tens of thousands of Palestinians who enter settlements across the West Bank every day for work or health care — shows that Palestinians are not “barred from entering” settlement lands.

Between Area A, Area B, and the settlements, then, roughly 15 to 28 percent of Jordan Valley land is accessible to, and accessed by, Palestinians.

So what of the remainder of Jordan Valley land — Area C territory that isn’t attached to settlements? Palestinians can enter much of this territory, too. Indeed, thousands of Palestinians live in Palestinian communities and tend Palestinian fields scattered throughout the Israeli-controlled section of the Jordan Valley. The village of Al Jiftlik alone, for example, takes up several percent of the Valley’s land.

Palestinians also access the same parks and open spaces that Israelis do in the Jordan Valley. They can hike from Area A to B to C. They swim at the Dead Sea’s Kalya beach, also in the Jordan Valley’s Area C. And they travel back and forth between these villages and attractions on roads running through Area C.

This isn’t to say the entire Jordan Valley is open to Palestinians. Some 46 percent of the Valley is designated as IDF firing zone, for example, which is largely off limits to civilians. Another nine percent of the Jordan Valley is the buffer zone along the border with Jordan.

Between these two areas, then, 55 percent of the Jordan Valley is generally off limits — but not, as the Times and B’Tselem disingenuously imply, to Palestinians specifically. Those areas are restricted to all civilians, Israeli and Palestinian alike. (Palestinians who had lived in the areas that become closed firing zones are permitted to enter and continue living in those zones.)

Nor is it to say that Palestinians easily obtain building permits in Area C, or that Palestinians or Israelis can utilize the Jordan Valley’s nature reserves for agriculture, grazing, or other economically productive uses. But the New York Times wasn’t speaking of such restrictions when it gave its inflated 85 percent figure. It was alleging that Palestinians, specifically, were barred from even entering 85 percent of the Jordan Valley.

The New York Times has told CAMERA it is looking into the issue. B’tselem did not respond to questions about how it reached its number, but in a 2011 paper the organization claimed Palestinians were unable to “use” roughly 77 percent of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area. That figure included vast areas in which Palestinians can enter (e.g. settlements), areas in which neither Israeli nor Palestinian civilians can enter (e.g. closed firing zones), and areas in which both Israelis and Palestinians can enter but not develop (e.g. park lands).

B’Tselem often uses sloppy and confusing language when describing land-use restrictions in the Jordan Valley. Consider the following example from a 2011 B’Tselem report about “Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea”:

Immediately after Israel occupied the West Bank, it began to close areas and declare them nature reserves and national parks. In the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea, Israel declared 26 sections of land nature reserves, a total of 318,000 dunams, which constitute 20 percent of the area. Fifteen nature reserves, amounting to 200,000 dunams (63 percent of the land allotted to nature reserves) were land that has been declared closed military areas. This fact shows that Israel did not show great concern for the environment of the area, or, alternatively, did not intend to use the closed areas for military purposes.

Israel developed only two of the nature reserves to accommodate visitors – Wadi Qelt (Ein Prat), which is located east of Jericho, and Ein Fashkha (Einot Tzukim), in the northern Dead Sea area. Two nature reserves have been classified national parks – Qumran, in the northern Dead Sea, which, like the previously mentioned two reserves, has been developed to accommodate visitors, and the Hashmonaim palaces, east of Jericho. Elsewhere, the lands seized as nature reserves were not developed for visitors, and had no fencing or marking of land indicating an intention to protect nature in the area. The only marking distinguishing between the reserves and the adjacent land is a sign of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.

On these lands, too, Israel forbids Palestinians to enter or remain there, whether to live or to graze their flocks.

The last sentence above is a prime example of B’Tselem’s slippery language, which appears to be meant to mislead readers about Israeli restrictions. For example, it is unclear to what “these lands” refers. Are Palestinians barred from all Jordan Valley nature reserves, including sites developed to “accommodate visitors”? B’Tselem doesn’t clearly say, and readers could easily conclude from the group’s language that Palestinians are barred from the developed parks that Israelis freely access. In fact, both Israelis and Palestinians can and do visit the parks.

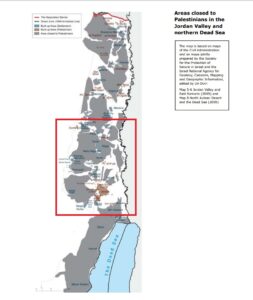

A B’Tselem map claims to show areas “closed to Palestinians.” The red box added by CAMERA encloses the Palestinian villages of Kafr Malek and Al ‘Auja. (Click to enlarge.)

And what, exactly, does it mean for people to be forbidden “to enter,” “whether to live or to graze their flocks”? Entering is one thing. Living and grazing is another. At any rate, Palestinians enter nature reserves where Israelis do, and Israelis cannot live or graze on those reserves where Palestinians cannot either.

B’Tselem has likewise labeled land used by Palestinians as being supposedly off limits to that group. In the adjacent map, for example, the advocacy group claims to show in gray areas that are “closed to Palestinians.” More detail is given in another map by B’Tselem (select here to display) which clarifies that the portions labeled as “closed” are made up of nature reserves (in green), firing zones (in red), and settlement lands (in blue).

But Palestinians frequently enter the supposedly closed areas. For example, a popular hike organized by a Palestinian NGO, in which Palestinian guides lead Palestinian and foreign hikers, runs right through one of the nature reserves that B’Tselem marked as off limits. (Select here to display the hiking route.) B’Tselem’s map and the hiking trail map are different aspect ratios, but by changing the dimensions, CAMERA roughly overlaid the two to show the approximate route of the trail relative to the nature reserve.

A guide that works with the hiking NGO confirmed by email that Palestinian guides can lead that portion of the hike “with no problem.” The gray area on B’Tselem’s map also includes Tomer, the Jewish settlement in which hundreds of Palestinians enter every day, according to the New York Times report published on the same day the paper endorsed B’Tselem’s false claims.

Whatever the exact percentage of off-limits land in the Jordan Valley, it seems clear that the figure is significantly less than 85 percent. And it should be equally clear to the New York Times that it is extremely misleading to cast restrictions that apply to both Palestinians and Israels as affecting Palestinians, specifically.

Fasayil

In a second error also published on Sept. 10, Times correspondent Isabel Kershner claimed that Fasayil, the Palestinian town in the Jordan Valley, is in Area C:

Fasayil sits in Area C, the large part of the West Bank technically under full Israeli control. The Palestinian Authority has paved the roads, run the school and clinic, and granted building permits for houses within village limits set by Israel.

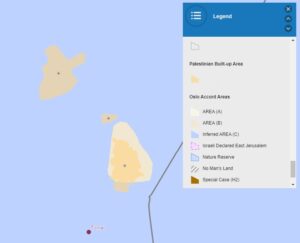

In fact, the main built-up village of Fasayil, also known now as lower Fasayil or Fasayil al Tahta, is located almost entirely in Area B, which is under Palestinian civil control. An offshoot known as Fasayil al Fauqa is in Area C.

After correspondence with CAMERA, the newspaper acknowledged that the built-up part of the village Fasayil is mostly designated as Area B, but pointed out, seemingly in reference to the sliver of Fasayil al Tahta that has overflowed past the boundaries of Area B, that the southern and western margins of the village are in Area C.

Despite the acknowledgement, the paper has asserted that it will not correct its straightforward error.

A United Nations Office Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs map shows the main portion of Fasayil (bottom right, darker yellow) sitting in Area B (bottom right, lighter yellow). Fasayil al Fauqa, in Area C, is seen at the top left