Has the Economist given up on even the pretense of fair reporting on the Arab-Israeli conflict?

Judging by the magazine’s March 6, 2010 article on Jerusalem, the answer is a definite “yes.” Despite its title, “A City That Should Be Shared,” and despite its posing as an informational piece about the dispute over Jerusalem, the article advocates on behalf of the Palestinian government, parroting its narrative while ignoring or distorting Israeli views.

From the sub-title, which labels disputed east Jerusalem land as “Palestinian ground,” through to the last paragraph, which casts as a nefarious “encroachment” any Jewish habitation in areas Palestinians demand for themselves, the article is saturated with bias.

No matter what action Israel takes, the Economist condemns it. The article vilifies Israelis for everything from “refashioning” the landscape to “conserving” it, from “encroaching” on Arab-populated areas to avoiding those areas. An archeological conservation is characterized as part of a plan by the Israeli government to rebuild the ancient Jewish temple – an outrageously false claim that echoes the most extreme allegations of those engaged in an incitement campaign against Israel.

Missing from the entire account, meanwhile, is any discussion of Israel’s historical, religious and cultural connection to the eastern sector of the city.

Downplaying the Jewish Connection to the Temple Mount

The holiest site in Judaism is the Temple Mount, the site of Judaism’s two ancient holy temples. Jewish reverence for the site long predates the building of two Muslim shrines, the Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa Mosque, on that site, and even predates the construction of the first Jewish Temple, which was built, according to Jewish tradition, on the Even Hashtiya, the foundation stone upon which the world was created. It is considered the epicenter of Judaism.

Yet the article refers to the site only by its Muslim names. Moreover, although readers are told that the area is home to “Islam’s third-holiest shrine,” they are never informed that it is Judaism’s holiest site:

Fearing that their half of the city is being cast in an increasingly Israeli mould, Palestinian stone-throwers clashed with Israeli forces on the Haram al-Sharif, or Noble Sanctuary, which Muslims venerate for its al-Aqsa mosque, Islam’s third-holiest shrine, and which Jews revere as the site of the biblical Temple.

The passage also dramatically distorts the stone-throwing incident, whitewashing and implicitly justifying the Palestinian violence. Palestinian stone-throwers did not merely clash with “Israeli forces,” but stoned Jewish civilians praying at the Western Wall below. As the Associated Press reported on March 5, “hundreds of Muslim worshipers emerging from prayers threw stones at policemen and Jews praying below at the Jewish shrine known as the Western Wall, according to Israeli police.”

Furthermore, it beggars belief to assume the incident was a spontaneous expression of Palestinian “fear.” That the incident occurred as Palestinians emerged from Friday prayers on the Mount suggests that Muslim worshipers were reacting to anti-Israel incitement in a sermon or even directives by clerics to launch attacks, as has been historically the case. (See, for example, “Calls for Jihad in ‘Defense’ of Muslim Holy Sites.”)

Archeology

If the Jewish connection to the Temple Mount is downplayed, its deep historical links to other parts of the city are cast as dubious claims that are part of a cunning ploy to deprive Arabs of their birthright.

“Israeli archeologists,” readers are told, “are scraping away the eastern parts of the city’s Arab surface in search of a Jewish past.”

Not only is the “Jewish past” of Jerusalem wrongly cast as a questionable claim that archeologists are desperate to prove, the statement also denigrates the professionalism of Israeli archeology, and of the authorities overseeing these digs, by insinuating that they focus on Jewish artifacts to the exclusion of everything else.

In the words of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the purpose of archeology in the area is not to prove what has already been proven — that Jerusalem has a rich and ancient Jewish history — but to gain “increased knowledge about every period.” And indeed, numerous excavations around Jerusalem focus on non-Jewish finds.

Contrary to The Economist‘s portrayal, it is not Israeli archeologists who are politicizing the city’s history, but rather Palestinian leaders and imams who have repeatedly denied the Jewish connection to Jewish holy sites. Yasir Arafat noted, for example, that there is not “a single stone proving that the Temple of Solomon was there, because historically the Temple was not in Palestine.” Likewise, Ikrima Sabri, until recently the Palestinian Authority-appointed mufti of Jerusalem and the highest ranking Islamic clerical authority in the PA, insists Jews have no connection to any part of the Temple Mount, including the Western Wall. In 1997, he proclaimed:

The Al-Buraq Wall [Western Wall] and its plaza are a Muslim religious property. … The Jews have no relation to it.

Still today, Sheikh Tayseer Tamimi, the chief Islamic judge of the Palestinian Authority, teaches that there is no Jewish connection to Jerusalem. (See more here.)

Such assertions are clearly relevant to the Economist‘s article, in part because they help explain one (but not the only) reason why many Jews cannot envision turning over their holy and historic sites to Palestinian control. But the article’s apparent purpose is to portray Israel as the villain and Palestinians as the victims; Palestinian denial of Jewish heritage, therefore, has no place in this skewed narrative.

The extent to which the author is willing to abandon journalistic ethics, misle

ad readers about Jerusalem archeology, and promote the most extreme and unreasonable Palestinian allegations becomes even more clear with the following assertion about an Israeli government-run development company:

To fulfil millennial Jewish yearning to restore the tabernacle, the company is also repairing what it says are ancient ablution pools.

The author seems to be referring to the Shiloah (or Siloam) pools, an archeological discovery of extreme historical significance – not only to Jews but to Christians as well. The notion that the preservation of this ancient site a step by Israel’s government toward “fulfilling” traditional Jewish yearning for a rebuilt temple is bizarre and ludicrous. While Jewish tradition eagerly anticipates a Messianic age wherein the Jewish Temple will be rebuilt, only a marginal group of extremists believe that the Israeli government should fulfil this Messianic aspiration. And in fact, the government actively combats any attempts to change the status quo on the Temple Mount. Although Palestinian leaders level false charges about Israeli plans to rebuild on the Temple Mount as part of an anti-Israel incitement campaign, it is unethical for a professional news organization to repeat such an outrageous libel as fact.

Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

The Economist, which has in the past criticized Israel for not allocating enough funds to eastern Jerusalem, now condemns the government for precisely the opposite – devoting resources to that sector. Among Israel’s sins, according to the article, is that “car-parks and conservation areas, rich with Israeli symbols, are sprouting across East Jerusalem.” Remarkably, even sewage work by Israel in Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem’s old city is cast in a negative light:

Inside the Old City itself, the Israeli government’s East Jerusalem Development company has begun to interrupt the main Palestinian artery into the ancient centre, for sewage works. Mr Barkat says the project will improve services, but Palestinians fear it presages fresh archaeological digs aimed at exposing Jewish ties along the pilgrims’ route to the Temple that Jewish groups from the religious right seek to rebuild.

Elsewhere, the magazine notes that “Israeli ambulances have sometimes been told not to venture into Palestinian areas to answer emergency calls” with the implication that Israeli ambulances are directed not to help Arab residents in need of urgent medical care. But contrary to the author’s suggestion, ambulances are not barred from entering eastern Jerusalem areas to evacuate or administer to sick Arab patients. Rather, they are directed to await a police escort before entering certain hostile neighborhoods. The reason for this – entirely omitted in the article – is that in recent years, Israeli ambulance crews who have entered hostile Arab neighborhoods unaccompanied have come under attack.

Nor are Israel’s traffic lights spared the Economist‘s censure. Traffic lights, readers are told, “flick green only briefly for cars from Palestinian districts while staying green for cars form Jewish settlements for minutes.”

Because this allegation appears highly unlikely, CAMERA asked the Economist to specify the intersections described in the passage. The magazine, unsurprisingly, has not substantiated its claim as of this writing. (See April 29 update here.)

“Facts on the Ground” in Eastern Jerusalem

The article is similarly disingenuous in its discussion of Jewish and Arab housing in Jerusalem’s eastern sector.

It asserts that, while the U.S. is seeking to restart negotiations, “the Palestinians have been literally losing ground.” Jewish building is described as “encroachment” by “zealots” who are engaged in “theft” of “Palestinian ground.” On the other hand, Palestinian building in the city is mentioned only in a brief passage that implicitly criticizes Israel for plans to demolish Arab homes that – although the magazine does not acknowledge it – were built illegally.

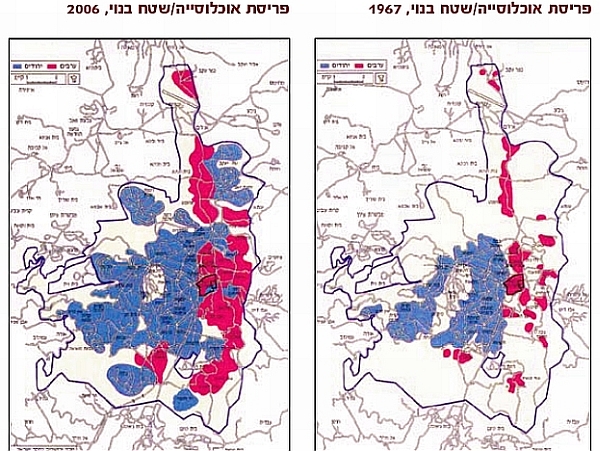

The article turns truth on its head. Far from “losing ground,” Palestinians have actually gained significant ground. The map below shows the growth of Arab-settled areas (marked in pink) in Jerusalem between 1967, when the city was reunited under Israeli control, and 2007.

A 1997 monograph written by former Jerusalem city planner Israel Kimhi demonstrates that during the thirty-year period after Israel’s reunification of Jerusalem (1967-1997), Arab building in Jerusalem outpaced Jewish building. Aerial photographs revealed that 13,600 buildings were constructed in Arab neighborhoods from 1968-1995. Between 1971 and 1994, the municipality granted building permits for 1.1 million square meters to the Arab sector. (This only accounts for legal Arab construction. Additionally, a significant proportion of Arab construction was done illegally, without permits.) Tax records indicated the addition of nearly 15,000 flats to the Arab sector of Jerusalem.

Indeed, the only mention of Arab building is the author’s assertion that last year, “America’s secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, berated [Jerusalem Mayor Nir] Barkat for his plan to demolish Arab homes to create a biblical tourist park in the valley below the Old City, where David is said to have composed his psalms.”

The magazine presents this issue as if Israel recently chose to create a theme park to replace longstanding, legally-built Arab homes. In fact, for hundreds of years, under both the Turkish and British administrations, the area in question was preserved as a public area meant for park development and conservation. It was only in recent years, under Israeli administration, that Palestinians began to build illegally in this area. This illegal construction has caused irreparable damage to antiquities here. (For more on the history of this area and context for the archeological park, read this Ha’aretz article by Nadav Shragai.)

That Israel did not decide to build this park as a pretext to displace Arab dwellers there is a fact confirmed also by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), which itself strongly tilts toward the Palestinian narrative. An OCHA document explains that, “Since the late 1970s, the Jerusalem municipality has designated all of the Al Bustan area of Silwan as an ‘open’ or ‘green’ area, where all construction is prohibited.” The illegal homes slated to be demolished were all built after the sensitive area was officially protected.

If the Economist meant to educate readers about the complexities of the dispute over Jerusalem, it failed miserably. If, on the other hand, its goal was to promote an inaccurate, unfair and one-sided account of current events, it sadly succeeded, but in the process proved that it has abandoned any pretense of journalistic integrity on Middle East issues.