- 489

- 497SHARES

10/19/21 UPDATE:

Bloomberg Corrects

After CAMERA and many of our readers informed journalists of the issues detailed below, Bloomberg corrected its piece so that it no longer misrepresented the timing of Hamas's violence and Israel's blockade. See below for a detailed update.

According to Bloomberg News, Hamas suicide bombing attacks were the result of Israel’s blockade of the Gaza Strip.

As Bloomberg’s CityLab journalist Zach Mortice put it his September 27 story, “Why the Gaza Strip May Be the City of the Future,”

[S]ince 2007, after the political wing of the Islamist group Hamas was elected to power, Gaza has been under an Israeli blockade. In response, Hamas militants have attacked Israel with suicide bombers and missile attacks… .

Both of these sentences, though, are effectively lies.

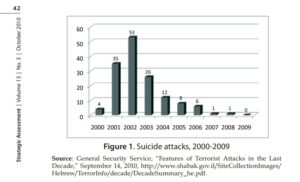

Hamas suicide bombings began in the 1990s, peaked during the round of Palestinian violence that began in 2000, and virtually ended after 2005. All of this, needless to say, was before Hamas’s election, and before the blockade. Missile attacks from the Gaza Strip likewise preceded the blockade, and in fact peaked just before Israel tightened its restrictions at its border crossings with Gaza, and peaked again just before Israel imposed its naval blockade.

On that note: Bloomberg’s message about the timing of the blockade—the author leads readers to believe it was a response to a Hamas electoral victory in 2007—is likewise spurious.

Hamas gunmen play with a phone in the Gaza office of Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas after the Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip in June 2007.

First, the Hamas electoral victory wasn’t in 2007, but in January 2006. A year and a half later, in mid-2007, Hamas violently wrested all control over the Gaza Strip from Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, and oversaw high numbers of rocket attacks from Gaza in the months that followed. It was then, in September 2007, that Israel clamped down on its border with Gaza.

The naval blockade, moreover, wasn’t imposed until 2009, during a round of fighting between Israel and Hamas that followed a surge of Palestinian rocket fire.

Why, then, does the story bungle cause-and-effect both for Hamas’s suicide bombings and for Israel’s blockade—each in a way that erases Hamas extremism and implies Israeli fault?

A hint might be found in the overall framing of the article, which attempts to legitimize facile analogies between Israel’s conflict with Hamas and racial tensions in the U.S.

In his opening sentence, the reporter connected the recent Gaza war with unrest over policing in U.S. cities. The recent fighting in Gaza, he wrote, would look familiar to Americans who’ve seen in their own country “streets flooded with protesters, engaged in a struggle against highly armed security forces on the streets of a battered-looking city.” Later, he approvingly cited the absurd claim that in Gaza, like in American cities, “the key issue is who has a right to the city.” (As in… Gaza City? The article doesn’t once mention Jerusalem.)

Of course, in the Gaza fighting, the key issue isn’t the right to Gaza cities, which Israel makes no claim to. The key issue—whitewashed by Bloomberg—was Hamas’s indiscriminate rocket fire, which began the exchanges of fighting, which are war crimes, and which are driven by the group’s extremist, antisemitic and violent ideology.

Bloomberg's piece opens with an analogy between Gaza and U.S. cities, immediately followed in the second paragraph by the falsehoods about the conflict:

When Americans turned on the TV or glanced at their smartphones for news of the deadly clashes that engulfed the Gaza Strip in May — or if they followed the more recent spasm of violence in August that threatened to break the region’s fragile truce — many saw scenes that looked familiar: streets flooded with protesters, engaged in a struggle against highly armed security forces on the streets of a battered-looking city.

In many ways, the political and physical conditions of the Gaza Strip are unique: Nearly 2 million people are packed into a 25-mile-long rectangle of land along the Mediterranean roughly the size of Philadelphia. For decades, the territory has been home to Palestinians displaced by the founding of the state of Israel in 1948, and subject to Israeli occupation since the 1967 Six-Day War. But since 2007, after the political wing of the Islamist group Hamas was elected to power, Gaza has been under an Israeli blockade. In response, Hamas militants have attacked Israel with suicide bombers and missile attacks…

As noted above, and as will be explored in greater detail below, Bloomberg’s characterization of cause-and-effect, both regarding the timing of the blockade and the timing of Hamas violence, is false.

The Elections and the Blockade

First, it is false to characterize the blockade as a response to Hamas’s electoral victory1.

The international community and Israel did impose some sanctions on the Palestinian government after Hamas won the legislative elections. But

- those elections weren’t in 2007, as Bloomberg led readers to believe, but in early January 2006;

- the sanctions were not a “blockade"; and

- the sanctions were not imposed because “the political wing” of an “Islamist group” won the election, but rather because Hamas is an internationally designated terrorist organization that rebuffed demands by the international community that it renounce violence, recognize Israel, and respect past agreements between Israeli and the Palestinians.

In late 2007, Israeli tightened its border with Gaza. That wasn’t a response to the elections a year and a half earlier, though. It wasn’t even the result of Hamas’s attack on Israel and kidnapping of Gilad Shalit in June 2006, shortly after the election. Rather, it stemmed from the mid-2007 fighting between two rival Palestinian parties, Hamas in Fatah, and the high levels of rocket fire from Gaza that followed.

In June 2007, after an increase in tensions between Hamas and Fatah, Hamas forces violently crushed security forces loyal to Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas and took over the Gaza Strip’s border crossings. As rocket fire from Gaza increased under Hamas’s rule, Israel in September 2007 declared Gaza a “hostile territory” and imposed stricter restrictions at its own border with the territory. Some media accounts sloppily referred to those restrictions as a “blockade.”

But even those policies, implemented by Israel at its own border crossings, were not a naval blockade. Indeed, some ships affiliated with a pro-Hamas group, the Free Gaza Movement, were permitted to sail to Gaza in 2008 without being intercepted by Israel’s navy.

Israel only imposed a naval blockade in January 2009, during the Hamas rocket attacks and fighting of Operation Cast Lead.

A Panel of Inquiry established by the United Nations Secretary-General summarized the distinction between Israeli policy relating to its border crossings with Gaza and the naval blockade as follows:

[T]he land crossings policy has been in place since long before the naval blockade was instituted. In particular, the tightening of border controls between Gaza and Israel came about after the take-over of Hamas in Gaza in June 2007. On the other hand, the naval blockade was imposed more than a year later, in January 2009. Second, Israel has always kept its policies on the land crossings separate from the naval blockade. The land restrictions have fluctuated in intensity over time but the naval blockade has not been altered since its imposition. Third, the naval blockade as a distinct legal measure was imposed primarily to enable a legally sound basis for Israel to exert control over ships attempting to reach Gaza with weapons and related goods. This was in reaction to certain incidents when vessels had reached Gaza via sea.

(For greater detail about the timeline, see the Turkel Commission Report beginning on page 28, paragraph 18.)

Hamas Violence

Bloomberg blames Hamas violence on the blockade, telling readers that “Gaza has been under an Israeli blockade” and that, “in response, Hamas militants have attacked Israel with suicide bombers and missile attacks.” This is an absurd and outrageous characterization.

Total suicide bombings by year. (Source.) Suicide bombings by Hamas, specifically, followed the same trajectory.

Suicide Bombings

Hamas suicide bombers were already murdering Israelis in the early 1990s. Throughout 1994, for example, the group bombed three civilian buses, killing 35. Dozens more were killed in a series of Hamas attacks in 1996 and 1997.

The violence, though, crescendoed in the early 2000s, with scores of Hamas suicide attacks killing hundreds of Israelis.

And what about after the 2006 Hamas electoral victory or the 2007 Hamas takeover and tightened border? There were no Hamas suicide attacks during those years. (There were two in 2008, in which one Israeli was killed.) And what about after the naval blockade in 2009? Again, there were no Hamas suicide bombings.

Rocket Attacks

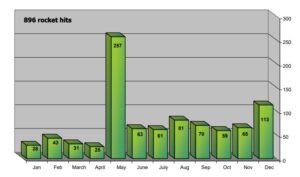

Rocket attacks into Israel surged in May 2007, just prior to Hamas's violent takeover of the Gaza Strip.

What of the missile attacks that were, in Blooberg’s account, a result of the blockade? Again, peaks in the number of attacks from Gaza belies this claim.

As documented by the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, rocket attacks, which had already increased in March 2006, when the Hamas prime minister took power, surged in May 2007, immediately prior to the Hamas takeover of Gaza, then continued at an relatively high level prior to Israel’s September clampdown on its border with Gaza:

In May 2007 Hamas initiated an escalation in rocket fire, attempting to end the violent confrontations with Fatah by deflecting the fire toward Israel. Once Hamas had taken over the Gaza Strip (June 2007) the level of rocket fire returned to “routine,” although the monthly average of more than 60 rockets was higher than the period before the takeover.

Rocket fire from Gaza surged again prior to the announcement of the naval blockade. In December 2008, Hamas insisted that a truce it had agreed to with Israel expired. Israel insisted otherwise, and implored Hamas not to resume its attacks. But the rocket attacks did resume. It was that surge which prompted Operation Cast Lead; and it was during that round of fighting that, on Jan. 3, 2009, Israel implemented its naval blockade. In the months that followed Operation Cast Lead and the imposition of the naval blockade, rocket fire from Gaza actually decreased. (See charts here.)

In short, rocket fire wasn’t a response to border restrictions or a naval blockade on Hamas-ruled Gaza. To the contrary, those Israeli measures followed the increases in rocket fire. Hamas’s suicide bomb war, meanwhile, was basically lost and over at the time the group took over Gaza. To suggest those bombings were a response to the blockade is not just a disservice to readers, it is historically illiterate.

Update: Bloomberg Corrects

After CAMERA and many readers contacted editors, Bloomberg corrected the passage that had inaccurately claimed, "since 2007, after the political wing of the Islamist group Hamas was elected to power, Gaza has been under an Israeli blockade. In response, Hamas militants have attacked Israel with suicide bombers and missile attacks." The corrected version notes instead,

The political wing of Hamas, which opposes Israel's right to exist, was elected to power in 2006; it took control of the enclave after a bloody schism with a rival Palestinian faction the following year. Israel — alongside Egypt — then placed Gaza under blockade as Hamas militants have continued to attack Israel.

A correction appended to the bottom of the piece hints at the changes. We commend Bloomberg for its corrections, which demonstrate a commitment to accuracy.

Footnote

1. In a technical sense, it is correct that the 2007 border clampdown and the 2009 naval blockade were imposed “after” the 2006 election—just as they were imposed “after” Hurricane Katrina. But this is pedantry. In a journalistic context, the word “after” is used as Bloomberg did to communicate that something was a reaction to another.