At the sacred Holy Fire ceremony Saturday in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre this weekend, the torch of anti-Israel vilification was burning bright.

In a deadly stampede, it matters not one bit if the faithful are Jewish or Christian, commemorating a rabbinic sage or Jesus’ resurrection. Regardless of the language or nature of the prayers, miracles can’t be counted on, year after year, to stand in for safety precautions. Nevertheless, for some of the media, the ecumenical threat to life and limb posed by large crowds unprotected by adequate safety precautions didn’t stand a chance against the overwhelming predetermined narrative alleging the Jewish state’s oppression of a persecuted Christian minority.

The Holy Fire ceremony at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, 2019 (Danels97, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Traditionally, many thousands of Greek Orthodox Christians observe Orthodox Easter by converging on the ancient church and surrounding streets in the Old City of Jerusalem, carrying torches of fire. It’s an event that holds tremendous religious significance, but also potential perils, with so many people and an abundance of flames crowded together in an ancient building and alleyways. Indeed, in 1834, hundreds died in a stampede at this very event.

And there have been smaller warnings since then. “In the past, the light set fire to people’s clothes, even their hair, said Tareq Abu Gharbiyyeh, East Jerusalem’s fire chief who has been fire-proofing the ceremony for the last 30 years,” the Jerusalem Post reported last year.

Indeed, church and Israeli officials need not look back to 1834 understand the harrowing risks of too many people in too small a space with insufficient safety measures, including emergency exits. It’s not even been two years since the 2021 Lag B’Omer disaster in northern Israel, in which 45 Jewish visitors were tragically crushed to death as a crowd overwhelmed the inadequate infrastructure at the Meron site. Some 40 days later, a large crowd of ultra-Orthodox Jews stood on overloaded stands in Givat Zeev; the collapsing bleachers killed two and injured some 184 worshippers.

These are not scenes that anyone should care to repeat — not the relevant religious authorities, and not the police responsible for ensuring crowd safety.

Thus, in light of the difficult lessons learned at Meron, police introduced new crowd restrictions at last year’s Jewish Lag B’Omer festivities and the Jewish priestly blessing gatherings. Last year’s Christian Holy Fire ceremony was no different than the Jewish religious gatherings. It likewise saw new restrictions, with a cap of 1800 people permitted to enter the church.

This year, officials from the Patriarchate of Jerusalem cynically rejected the professional advice of their own engineer to maintain last year’s limit of 1800 worshippers within the church, and then cast Israeli police efforts to enforce their professional’s safety recommendations as oppressive heavy-handedness impinging on their freedom of religion.

The church’s messaging that Israeli police efforts to enforce a safe number of worshippers represented “unreasonable restrictions” spread like wildfire, with leading international wire services providing coverage heavily focused on the church’s complaints about police restrictions while failing to report that it was the church’s own engineer who provided the maximum figure of 1800 worshippers.

The Times of Israel commendably reported the important information ignored by the international media (“Holy Sepulchre letter undermines church allegations on Israeli worship limits“):

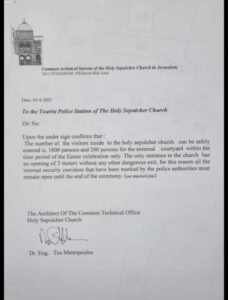

Contradicting allegations by church leaders earlier this week that Israel Police was unnecessarily infringing on Christians’ freedom of worship, a letter reviewed by The Times of Israel on Friday indicates that restrictions on Saturday’s Holy Fire ceremony were imposed at the request of a Greek Orthodox official.

The April 3 letter, sent to the police station outside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre by church architect Teo Metropoulos, stresses that the maximum number of visitors for the ceremony should be 1,800 inside the building and 200 more in the courtyard.

The letter also emphasizes that “the only entrance to the church has an opening of 3 meters without any other dangerous [sic] exit,” and asks police to keep all internal corridors open.

In two stories (“Orthodox Christians attend Holy Light in Jerusalem under police curbs,” April 15) and (“Israeli curbs on Orthodox church crowds in Jerusalem draw Easter ire,” April 12), Reuters neglected to mention Metropoulos’ letter. Given that the church engineer’s letter undermines Christian leaders’ claims of Israeli police imposing “heavy-handed” measures, it is highly relevant to the coverage and should have been reported. Two days before Henriette Chacar‘s April 15 story citing Christian anger at the police allegedly keeping Christians away from their sacred ceremony, the police had already clearly reported that the figures originated with a safety engineer representing the church. The police tweeted April 13: “Regarding the Holy Fire event taking place on April 15, 2023 in the Old City of Jerusalem, we clarify: limiting participants is not a result of a police initiative, but a necessary safety requirement, per the professional analysis of the safety engineer on behalf of the churches.” (Emphasis added.)

In two stories (“Orthodox Christians attend Holy Light in Jerusalem under police curbs,” April 15) and (“Israeli curbs on Orthodox church crowds in Jerusalem draw Easter ire,” April 12), Reuters neglected to mention Metropoulos’ letter. Given that the church engineer’s letter undermines Christian leaders’ claims of Israeli police imposing “heavy-handed” measures, it is highly relevant to the coverage and should have been reported. Two days before Henriette Chacar‘s April 15 story citing Christian anger at the police allegedly keeping Christians away from their sacred ceremony, the police had already clearly reported that the figures originated with a safety engineer representing the church. The police tweeted April 13: “Regarding the Holy Fire event taking place on April 15, 2023 in the Old City of Jerusalem, we clarify: limiting participants is not a result of a police initiative, but a necessary safety requirement, per the professional analysis of the safety engineer on behalf of the churches.” (Emphasis added.)

But Chacar failed to make clear that the engineer was a church official, citing only police claims about an unspecified safety engineer. Chacar’s report obscured: “‘These numbers are based on a safety engineer’s analysis,’ said an Israeli police spokesperson. A statement by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate called into question the engineer’s conclusions.”

See also “BBC’s Knell Amplified Church’s Politicised Talking Points“