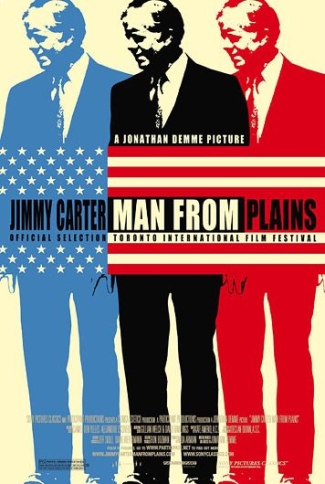

Jimmy Carter Man from Plains (2007)

Sony Pictures

Written and Directed by Jonathan Demme

125 minutes

If the viewer of a documentary is left pondering difficult, unanswered questions as the credits roll, it could be a sign that the film was nuanced and thought-provoking.

But not necessarily. The riddle-like question that comes to mind after sitting through Jimmy Carter: Man from Plains, Jonathan Demme’s slow-moving documentary about the former president and his controversial book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, is this: Should a film that faithfully reflects the contents of an error-filled book be considered accurate, or inaccurate?

It’s hard to say. The old cliché that “the camera doesn’t lie” certainly applies to the high-definition video cameras used to record Carter’s every move during the publicity tour for Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid. The footage of the president-cum-author discussing his book with Larry King, Wolf Blitzer, Jay Leno and other notable media stars is unquestionably authentic. So are the shots of him preaching in church, lecturing to an audience at the Carter Center, and discussing his schedule with the Simon & Schuster publicist. (Yes, the movie is that exciting.)

The film also exhibits, truthfully and without distortion, Carter’s statements about the Arab-Israeli conflict. The camera doesn’t lie. This is genuine Jimmy Carter.

Ironically, it’s by way of this accurate reflection of Carter’s Mideast commentary that the film actually becomes a purveyor of falsehoods. Because while the camera doesn’t lie, the same cannot be said for Jimmy Carter.

The many factual errors in Palestine: Peace not Apartheid have been widely discussed and well documented. Former President Bill Clinton described the book as “not factually accurate and … not fair.” His chief Middle East negotiator Dennis Ross said it “badly misrepresents” Clinton’s peace proposals. Kenneth Stein, the first permanent executive director of the Carter Center, severed his ties to that organization after noting the “egregious errors of both commission and omission” in Carter’s polemic. (Fourteen members of the Center’s advisory board resigned for similar reasons.)

A reviewer for the Washington Post charged Carter with “manufactur[ing] sins to hang around the necks of Jews when no sins have actually been committed.” A reviewer for the New York Times called the book “a distortion.” According to a New Republic blog, the book is “tendentious” and “dishonest.” And CAMERA has meticulously documented and rebutted dozens of specific factual errors from Carter’s book and media appearances.

But the documentary glosses over these challenges to the accuracy of the book, and instead frames the controversy as mostly revolving about the Carter’s use of the word “apartheid” in the title. Again and again, the film shows interviewers asking about the title. Again and again, we hear Carter’s rehearsed response. To be sure, the wrongheaded association of Israel with the racist South African regime elicited its share of criticism; but it may have been more interesting, not to mention educational, had the filmmaker also explored the specific challenges to the “facts” upon which Carter rests his apartheid slur.

Instead, the documentary propagates some these false facts by allowing Carter to repeat them unchallenged.

After Carter sketches a map of Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, telling the camera that “this is how the holy land was divided after the 1967 war” (actually it is how it was divided after the 1948 war), he asserts that the “wall” (actually a protective barrier that is mostly fence) is “all built on Palestinian land.” Later in the film, Carter is seen repeating this assertion and pushing a reluctant CNN interviewer into parroting the claim, which originates on page 190 of Peace Not Apartheid. It is a complete fabrication. According to United Nations numbers, roughly 60 miles of barrier is being built not on “Palestinian land” but along the 200 mile boundary line between the West Bank and Israel, or in some cases inside Israel itself. Demme does not share this fact with viewers.

Even the sections of the barrier that veer into the West Bank are not built on “Palestinian land,” but rather on land claimed by the Palestinians. Despite Israeli willingness to hand over large swaths of the West Bank, this land — especially territory along the barrier path — remains for now disputed. In fact, sections of it would have officially become part of Israel under some international peace plans.

Carter similarly invents facts about the barrier between the Gaza Strip and Israel, telling viewers that the Gaza Strip is surrounded by a “complete wall” (false) with “only two openings” (false) and that Israel controls both (false.)

Broader accusations against Israel are also allowed to pass with scant investigation. In the documentary’s opening sequence, Carter explains that his family has owned and farmed land in Georgia for more than 170 years, which, he suggests, allows him to understand how horrible it would feel for a family that cultivates olive trees and grazes goats to have their land “taken away.” If it isn’t clear enough that he’s referring to the Arab-Israeli conflict, later in the movie he makes clear that olive trees belong to the Palestinians, and the “foreign people” who cut them down are the Jews.

This could have been a fascinating opportunity to explore the dissonance between Carter’s negative tone when speaking about the Jewish return to their ancestral homeland, which had been inhabited by Jews from time immemorial, and his proud discussion of his own ancestors who moved to Georgia, a state from which the Native American inhabitants were forcibly cleansed. His relatives found a home in Georgia roughly at the same time as the “First Aliyah,” which brought a wave of Jewish immigrants fleeing persecution to settle in uninhabited areas of Palestine. Carter explains in the documentary that his family came to Georgia in 1833. He doesn’t explain that this was precisely during the period during which the Creek Indians were expelled from the state, with their land then being distributed to whites by lottery. Did Carter understand that, unlike the Creek and Cherokee Indians forced out of Georgia, Palestinian landowners had willingly sold land to the Jews? Did he understand that ancient communities of Jews had been forced from their homes in Hebron and elsewhere in Palestine?

It is little surprise that director Jonathan Demme did not ask such questions. When asked by an NPR interviewer why he made the movie, he replied that it was in part because Carter is “an American who I have great admiration for.” He also admitted that Carter saw the documentary as a forum “to express his ideas …, to expand his audience, to get the word out a little bit more.” The director didn’t disagree with this assessment about the purpose of the film.

Still, “Man from Plains” isn’t exactly Peace Not Apartheid in movie form, even if it sometimes feels that way. Viewers do get to see short clips of Dennis Ross, Kenneth Stein and Alan Dershowitz, for example, taking issue with the book. One specific challenge is raised about

the accuracy of maps that appear in the book. More general criticisms are openly acknowledged. But if the small amount of time given to critics of the book feels a bit like a fig leaf, that’s because it is. As an AP reviewer noted, “Demme said he made sure to include opposition voices so he would not face similar criticism that Carter did with his book.” These opposition voices, moreover, were more than neutralized by Carter’s repeated insistence that his book was fact-checked and is entirely accurate.

In the end, it’s hard to disagree with the Washington Post’s assessment of the film as “largely hagiographic.” This isn’t the critical examination it could have been, and those hoping for the answers to — or even the asking of — difficult questions will surely be disappointed.