- 544

- 552SHARES

In the days leading up to the 20th anniversary of the Sept. 11 terror attacks, NPR dedicated special coverage to the event and its implications. The way the news organization spun its story about Israel during that coverage, though, was anything but special. It was just more of the same slanted reporting, effectively erasing Palestinian terrorism while shifting blame for the violence onto the targets.

NPR has long been seen as biased against Israel, and those suspicions have been borne out by in-depth studies, moments of candor by NPR reporters, and even examples of NPR journalists amplifying antisemitism.

The online version of NPR’s broadcast purporting to tell how 9/11 affected the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The latest example of skewed reporting, a September 10 Morning Edition segment anchored by NPR’s Daniel Estrin and entitled “How the Events of 9/11 Still Affect the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” was a tall tale of Palestinian leaders behaving responsibly after September 11 and Israel being responsible for Palestinian suicide bombing attacks on Israeli civilians.

In the account told by Estrin and his featured speakers, 9/11 came one year into a Palestinian “uprising” that involved “militant bombings and shootings and attacks by Israeli troops.” After the attacks on America, Palestinians, who Estrin says were merely “fighting for an independent state,” didn’t want to be conflated with real terrorists like Al-Qaida. So Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat called for an end to the intifada and, “for a short time, violence decreased.”

Stopping attacks on civilians certainly sounds like the responsible thing to do. But the violence continued. “[I]t didn’t stop,” said one of the segment’s speakers, “and not because of Yasser Arafat, because of the Israeli side.” Estrin elaborated: “In January 2002, Israel killed a top West Bank militant, restarting a policy of assassinations.

The NPR anchor did admit that “not everyone puts the blame on Israel,” which is perhaps a concession, although “not everyone” certainly sounds a lot like “just about everyone.” The assassination, Estrin continued, was followed by a Palestinian suicide bombing in March 2002, on Passover. And that attack, coupled with Israel’s sense that America would understand its concerns after 9/11, led to an Israeli invasion of the West Bank, “killing hundreds of Palestinians.”

The general message of the segment, then, is that while 9/11 convinced Palestinians to turn away from violence, Israel used the attacks as an excuse to go on the offensive. And because of that, Israel, the victim of ongoing Palestinian terror attacks, should be blamed for those war crimes targeting its civilians.

RACHEL MARTIN, HOST:

Twenty years ago this week, planes crashed into the Twin Towers, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania. On the other side of the world, Israelis and Palestinians were deep into the second intifada.

NPR’s Daniel Estrin spoke to some who were involved in that fight. They think that the aftermath of 9/11 affected their conflict in ways still evident today.

DANIEL ESTRIN, BYLINE: On September 11, 2001, American television viewers saw this scene from Jerusalem. This is Fox News.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER: The V sign for victory being displayed in East Jerusalem today among jubilant Palestinians.

ESTRIN: Some were jubilant to see Israel’s ally, America, hit. Yasser Arafat, the Palestinian leader, ordered his security services to quickly quash any scattered celebrations. And he issued a statement.

Aide Nabil Amr tells me he helped him draft it.

NABIL AMR: We want to send a message to the world. We are not with al-Qaida and its activities, that we are completely against the terror.

ESTRIN: At that time, the second intifada, the Palestinian uprising with militant bombings and shootings and attacks by Israeli troops, had been going on for a year. Palestinians were fighting for an independent state.

But Amr says Arafat was worried Palestinians would be labeled terrorists.

(SOUNDBITE OF FOOTSTEPS)

ESTRIN: Nasser Jumaa was once a leader of the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades militant group. We walk up stone steps to a historic Turkish bathhouse in the West Bank city of Nablus, where his men would hold meetings.

NASSER JUMAA: (Speaking Arabic).

ESTRIN: He says, “Arafat’s emissaries told them he wanted to take a major step and end the intifada. Because America had declared war on terror, he feared the world wouldn’t be sympathetic to the Palestinians’ armed fight.” And for a short time, violence decreased.

Retired Israeli Army Brigadier General Shlomo Brom thinks it was an opportunity that could have changed history.

SHLOMO BROM: Yasser Arafat wanted to distance himself from this axis of evil. And the only way to do it was to stop the intifada. But it didn’t stop, and not because of Yasser Arafat, because of the Israeli side. We missed this opportunity.

ESTRIN: In January 2002, Israel killed a top West Bank militant, restarting a policy of assassinations.

BROM: When you get this intelligence about the bad guys, you want to kill them. So we couldn’t overcome the urge.

ESTRIN: Not everyone puts the blame on Israel. And former commander Jumaa says Arafat couldn’t control all the militants anyway. In March 2002, a suicide bomber killed 30 civilians during a Passover meal at an Israeli hotel.

Amos Gilead was a senior army officer then.

AMOS GILEAD: In Passover, wow – the moment I got the message, I said, that’s it. Now we would invade.

ESTRIN: Six months after 9/11, Israel launched a full-scale invasion of the West Bank, with tanks on the streets, killing hundreds of Palestinians. Israel’s view was the U.S. would understand.

GILEAD: It’s American expression – very simple one. Terror is terror.

ESTRIN: The peace process for a two-state solution never fully regained momentum. Israelis widely believe their security requires keeping the West Bank under their control.

Retired Brigadier General Brom says, that’s the legacy of the gruesome violence of the intifada.

BROM: It completely destroyed the mutual trust between the two sides – completely destroyed. And it never returned.

JUMAA: (Speaking Arabic).

ESTRIN: Nasser Jumaa, the former militant, thinks the aftermath of the September 11 attacks brought an end to the dream of a Palestinian state as the U.S. and Arab states had other things to deal with besides forcing compromise between Israelis and Palestinians.

Daniel Estrin NPR News, Nablus, the West Bank.

A casual listener might have noticed some examples of NPR’s anti-Israel slant.

If an anchor on NPR’s Morning Edition that same day referred to al Qaida bombers around the world as “terrorists,” and another NPR anchor recently described the those who attacked US soldiers securing the airport in Afghanistan as “terrorists,” then why did Estrin cast Palestinian attacks targeting civilians only as “militant bombings and shootings”? By any measure, suicide bombings targeting civilian buses, restaurants, and dance clubs are terror attacks. There’s should be no exemption for the murder of Israeli Jews.

Why, too, did Estrin insist the intifada was just a Palestinian “[fight] for an independent state” without acknowledging that the intifada’s attacks on Israel began just after Palestinians rejected an offer of statehood?

And why did he cast the anti-Israel violence as connected to a worthy goal—“independence,” after all, sounds innocent if not noble—when so many of the intifada’s devastating attacks were at the hands of extremists seeking no less than the destruction of Israel?

It’s the typical bias we’ve come to expect from NPR. A deeper look reveals further falsehoods that, twenty years after the events described, might not be so apparent.

Palestinian Violence After 9/11

Did Palestinian violence against Israelis really decrease after 9/11, as listeners were told?

Before the attacks, in the eleven full months between the start of the intifada in late September 2000 and September 11, 2001 an average of 15 Israelis were killed per month by Palestinian attackers.

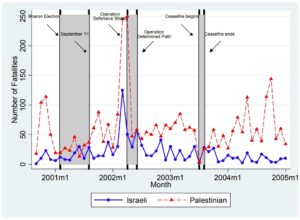

The number of Israeli fatalities continued on its upward trend after Sept. 11, 2001, and December 2001 was the deadliest month yet. Click to expand. (Image source.)

By contrast, in the three months after September 2001 and before January 2002, when Israel supposedly ruined the relative calm by killing a Palestinian terrorist, an average of 22 Israelis were killed per month.

So contrary to NPR’s account of a Palestinian leadership chastened by 9/11, deadly Palestinian violence increased after the al Qaida attacks. Indeed, December 2001, the month just prior to the killing of the Palestinian terrorist, was by far the deadliest month for Israelis since the start of the Palestinian campaign of violence, with 40 Israelis killed.

Generally speaking, then, there was no decrease in deadly violence.

Only when zooming in and scrutinizing the weekly zigs and zags of the macabre ledger can one see a brief downturn in casualties—not in the weeks after September 11, as NPR led listeners to believe, but after the carnage of December 2001.

That month opened with two grisly Palestinian suicide bombings. On December 1, three bombs ripped through Jerusalem’s Ben Yehuda St, which the Guardian correctly described as “a pedestrian mall of shops and cafes that is a magnet for teenagers.” The newspaper continued:

The explosions from the suicide attacks spewed body parts and glass from shattered shopfronts down several hundreds yards of street, and left a stench of burning hair. The blasts left the pavement littered with shoes, handbags, and chunks of flesh and large splashes of blood where people were hit by flying glass and shrapnel from the nail-studded bombs.

Eleven young Israelis were killed.

After the attack, President George W. Bush demanded that Yasir Arafat “act swiftly and decisively” against Palestinian violence. Similar messages were conveyed to the Palestinian leader by Colin Powel, the U.S. Secretary of State, and Anthony Zinni, an American envoy who recently arrived in the region to broker true talks.

The wrecked hull of Haifa city bus 16, destroyed by a Palestinian suicide bomber in an attack that killed 11 people.

But the next day, 15 more people were killed in the coastal town of Haifa when a Palestinian bomber detonated himself on a crowded city bus, and another Israeli civilian was shot dead. Again, eyes turned to the Palestinian president: “It is a moment of truth, Mr. Arafat,” said Secretary of State Colin Powell on CNN.

And still, the violence continued. After two more suicide bombers that month injured (but failed to kill) Israeli Jews, a third mass-casualty attack shook the country. On December 12, a military-style ambush targeted a bus carrying religious Jews, who were mowed down with bombs, grenades, and guns. Ten were murdered.

“This is clearly a turning point,” Mideast analyst David Makovsky said of the spate of killings. After the attack, Israel announced it was cutting of contact with the Palestinian leader, and parked tanks outside his offices. “The spotlight is on Arafat,” President Bush said. The United States pulled its envoy from the region, and Secretary of State Powell announced that Arafat “hasn’t done enough” to end the violence. European leaders, too, put pressure on Arafat.

It was only then that Arafat felt compelled to dial back violence. As the New York Times reported then, “Apparently, he finally took to heart what the United States and the European Union had been telling him for weeks: that the Palestinian Authority had to crack down on Islamic extremists and to get anti-Israel violence under control, or risk international isolation and perhaps its own collapse.”

It wasn’t the shadow of 9/11 that spurred Palestinian leaders to tell the world “we are completely against the terror reduce attacks,” as NPR’s segment conveyed. Rather, it was the pall from Palestinians’ own indiscriminate attacks that forced Arafat’s hand. “With the United States and Europe pressuring him hard to stop anti-Israel terrorism,” a Dec. 16 New York Times story noted, “Yasir Arafat went on Palestinian television tonight to appeal for a halt to all armed activities against Israelis.”

Although an Israeli was murdered in a Palestinian attack the next day, the pressure did have an effect on the ground. Arafat’s soldiers confronted some of the Palestinian groups, like Hamas and Islamic Jihad, most responsible for suicide bombings. And although Israel believed the steps by Arafat were little more than a temporary, tactical move to ease pressure on him, it acknowledged that Palestinian shootings, bombings, stabbings and grenade attacks dropped from an average of 18 per day to 11 per day over the next two weeks. The number of Israelis killed likewise shrunk.

A Boatload of Danger and Provocation

NPR and Estrin’s account flagrantly misled listeners about what was actually an increase Palestinian violence after September 11. But were they right, at least, in promoting the idea that Israel had stomped into the void with an unprovoked killing, and thus was responsible for prolonging the intifada?

According to researchers at the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, that’s not how things tended to work. An empirical analysis of fatalities in the conflict found that successful Israeli assassination attempts against Palestinian terror leaders generally led to a reduced number of Israeli fatalities, not an increase.

Still, it’s possible that the Jan. 14, 2002 killing of Raed Karmi, a terror leader responsible for killing about a dozen Israelis, was an exception. His death was followed by an increase in Palestinian terrorism and an expansion of violence by Karmi’s Fatah faction. But even if so, NPR failed listeners once again with a selective a distorted history — one that leaped obliviously from Arafat’s crackdown on violent groups to the killing of the Palestinian militant on January 14 — and thus skipped over one of the most significant events of the intifada.

On Jan. 3, 2002, Israeli naval commandos intercepted a ship, the Karine A, as it traveled from Iran to the eastern Mediterranean Sea smuggling 50 tons of weapons to Arafat’s Palestinian Authority. If the cargo had successfully entered the Palestinian territories, as top Palestinian officials had planned, the rockets, sophisticated explosives, and other military weaponry would have posed an unprecedented threat to Israeli population centers. The discovery of the shipment, and Arafat’s empty pleas of innocence, were like a suicide bomb to the Palestinian leader’s credibility.

After the capture of the ship, Israel’s prime minister announced that Arafat had made himself “a bitter enemy of Israel.” The defense minister said the affair “proves that the Palestinian Authority is directed toward war, while Israel is working to obtain a cease-fire.” And the chief of staff said the Palestinian government was “drenched from head to toe with terror.”

It wasn’t only Israelis who saw this as a watershed event. President Bush later explained that the smuggling attempt, and especially Arafat’s denials of responsibility afterward, led him to never trust the Palestinian leader again, and he concluded that “peace would not be possible with Arafat in power.”

Javier Solana, the European Union’s foreign affairs and security chief, described the discovery as “a substantial change in the Middle East conflict,” and told European parliamentarians that it led to lack of trust between the sides that seemed impossible to bridge.

Even New York Times editorial writers, not known for an excess of sympathy for Israel, lamented after the interdiction that “every time Washington appears to make a little progress [with diplomacy], a new Palestinian suicide bombing or other provocation intervenes to preclude further discussions.” A story in the news pages acknowledged that the smuggling episode, coupled with a Jan. 9 Palestinian attack that killed four Israeli soldiers, “threatened to reignite the tit-for-tat violence that has blocked efforts to reopen peace negotiations.”

This was the context that Israel killed Karmi, a wanted terrorist whom the Palestinian government claimed it had imprisoned but who in fact was free.

The NPR segment was a work of complex choreography. Estrin leaped from September 11, 2001, floated over the Palestinian massacres of early December, and swung Arafat’s late-December crackdown from its actual place on the timeline to an earlier date. He then jumped past the capture of the Karine A and the killing of four Israelis before landing on January 14, when Karmi was killed.

All this to promote the narrative of Palestinian innocence and Israeli guilt that so appeals to NPR.

Arafat’s Faults

Listeners wouldn’t know it, but even one of the Palestinian guests on the segment doesn’t quite agree with NPR’s narrative. Nasser Jumaa was a leader of the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, an internationally designated terror organization responsible for dozens of suicide bombings and other attacks against Israelis. And even he has been more willing than NPR to place responsibility on Yasir Arafat and the Palestinian leadership.

Jumaa certainly faults Israel, as would be expected, and he does believe 9/11 changed international opinion. But unlike NPR and Estrin, he hasn’t pretended the attacks changed Palestinian behavior. “It was clear that the Israelis closed the door on us, but also—let me be frank—the Palestinian leadership under Arafat was folly, mistaken,” he told the Independent in 2005.

Part of that folly was continuing terrorism after the attacks on America. “The resistance after 11 September should have kept itself far away from terrorism,” Jumaa said. It didn’t. “We…should have behaved more wisely,” he continued, saying it was the ongoing Palestinian terrorism that allowed Israel to make the case after 9/11 that the Palestinian groups were, like al Qaida, terrorists. And Jumaa continued to say what NPR wouldn’t:

Hamas’s strategy of suicide bombing, which helped to “drag” the Fatah factions into suicide attacks on Israeli civilians, was, he believes, a catastrophe. “The leadership led by Arafat took us to disaster … This is the fact.”

In another interview that year, he made similar arguments. The “resistance,” he told Al-Ahram Weekly, “made a number of mistakes.” One was that different Palestinian groups “vied off one another, without a clear vision, specifically in regard to the strategy of suicide operations, which in the end classified the Palestinians and the Palestinian resistance as terrorists,” an acknowledgement that his own group’s suicide bombings weren’t, as NPR suggested, simply a response to Israel’s assassination of the terror leader Karmi, but were part of a competition between terror groups over which could cause more destruction.

Why such admissions didn’t appear in NPR’s segment, which after all quoted Jumaa, is anyone’s guess. Did he simply not repeat for NPR what he’s said elsewhere? Maybe. But considering the other liberties taken in Estrin’s segment, it would be fair to ask whether such forthrightness about Palestinian responsibility just isn’t what the broadcaster is looking for.