- 456

- 457SHARES

Demonstrating a total abandonment of the journalistic imperative mandating strict adherence to factual accuracy, The New York Times is refusing to correct a blatant error: the misidentification of Rameh, an Arab town in northern Israel, as “Palestinian.”

The Oct. 19 food article, “Where Olives Go Back 7,000 Years,” (online here and in print Oct. 20), by cookbook author Reem Kassis carried the subheadline, both online and in print:”Rameh, a Palestinian town surrounded by olive groves, has long had a reputation for producing especially good oil.”

Similarly, the article itself erroneously states in the first paragraph: “It was the dead of winter in this Palestinian mountain village in the Galilee . . . ” Contradicting the “Palestinian” characterization, the article’s dateline accurately refers to “Rameh, Israel.”

While some residents of Rameh might identify as Palestinian – just 7 percent of Arabs living in Israel self-identify primarily as Palestinian, according to a 2020 survey – the geopolitical reality is that Rameh is located within Israel’s internationally-recognized pre-1967 armistice lines. Thus, Rameh is internationally recognized as part of the State of Israel. Does The New York Times oppose the international community on this point?

Before deciding whether Rameh has best olive oil in the world, 1st @nytimes should work out *where* in the world it is. It’s in northern Israel; it’s not a “Palestinian town.” @CAMERAorg urges correction https://t.co/ZK2n4VKe44 pic.twitter.com/B8jwrLdx4w

— Tamar Sternthal (@TamarSternthal) October 20, 2021

The Times yesterday declined to correct the basic geographical error, writing to CAMERA:

Rameh is both an Arab town and a Palestinian one, and either is correct. Arab citizens of Israel increasingly identify as Palestinian, a subject we’ve written much about.

Calling it a Palestinian town refers to the character and inhabitants of the town and doesn’t imply Palestinian sovereignty or Israeli occupation. And the dateline on the article says Rameh is in Israel.

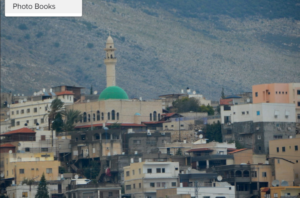

Rameh in the Galilee, northern Israel (Photo by Adam Fagen/Flickr)

What data does The Times have specifically on Rameh demonstrating that unlike Arabs across the rest of Israel who overwhelmingly do not identify as Palestinian, Rameh residents predominantly embrace that identity? Is the Times able to substantiate the assertion that Rameh is an anomaly among the rest of the country’s Arabs, who overwhelmingly don’t identify as Palestinian?

The Times justifies the decision not to correct with the argument that “Arab citizens of Israel increasingly identify as Palestinian.” (Emphasis added.) The alleged increase is from when to when? From what figure to what figure? The reality is that the numbers sometimes go up and sometimes down and one could just as easily point to two dates showing an increase in Israeli identification. To claim that the Arabs in Israeli “increasingly” identify as Palestinian is completely arbitrary. Indeed, in 2019, 18 percent of Arabs in Israel said “Palestinian” was their main identity. That figure decreased to 7 percent in 2020. Similarly, in 2015, 20.3 percent identified as “Palestinian Arabs” in 2015. That figure plummeted to 12.8 percent by 2019.

In other words, citing a supposed “increase” in the Palestinian self-identification of Arabs living in Israel is disingenuous rubbish with zero journalistic justification.

On the basic issue of clarity and reading comprehension, mislabeling the town as “Palestinian” impedes readers’ understanding. For instance, when the article states “Rameh’s olive oil has long had a reputation for being the best in the country,” which country does The Times mean? Israel or the “country” of “Palestine”?

Similarly, if Rameh’s residents are “Palestinian,” then readers cannot be faulted for wrongly assuming that the town’s people are subject to alleged “egregious Israeli restrictions on Palestinian livelihood.” Nor can misinformed readers be blamed for wrongly believing that Rameh’s residents were deprived of the coronavirus vaccine and forced into a coronavirus lockdown even as neighboring Israeli communities had access to an ample supply (“Palestinians Go Into New Lockdown While Awaiting Vaccines“).

The New York Times can’t have it both ways. If it regularly uses the term “Palestinian” to refer to Arabs living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, then references to Arab towns in Israel as “Palestinian” are extremely misleading. Residents of the latter are Israeli citizens, with all the rights and benefits that entails, and are subject to a completely different set of circumstances than Arabs living in the Palestinian territories without Israeli citizenship.

Blaming Israel’s Founding For Fewer Farmers

Separately, the article advances the fallacious notion that Israel’s founding and the state’s subsequent policies are solely responsible for Rameh’s decreased olive oil output. Kassis reports:

Before the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, Rameh’s olive groves could produce up to 250,000 liters in a high-yield year. The oil was sold widely across the country, and in Lebanon and Syria as well. But production has dropped in the seven decades since.

Nasab Hussein, 34, a cultural researcher and author, and Ms. Hussein’s niece, documents this change in her book “Rameh: An Untold Story,” published in 2020. She explained how the expropriation of land from Palestinian farmers and the closure of borders with Syria and Lebanon, which led to a labor shortage, diminished the economic viability of olive farming. “You really can’t separate our olive story from the political one,” she said.

People used to work and go to school in Rameh, she said, and still relied on olive farming for income. But from 1948 until 1966, Israeli military rule restricted movement, preventing farmers from accessing their groves. Trees were neglected, yields became much lower and prices dropped. Today, far fewer families rely on olive farming than in the past, and it no longer sustains the village economically. It’s difficult even to know how much oil Rameh produces now.

Of course, other unmentioned factors contributed to Rameh’s decreased reliance on olive cultivation, factors that apply to much of world: development, increased education, and professional diversification.

Indeed, Haaretz quoted a Rameh-born Arab who provided a much more complete explanation for the decline of the town’s olive industry:

“The whole industry is down,” says [Rameh native] Halaf, a real estate assessor. “The demand is there, but the price is unrealistic. People are looking for what’s cheap, and here we work by hand. Rameh olives are raised without artificial irrigation or fertilizer. The yield is relatively small and people don’t want to pay the high price this dictates.”

These days, Halaf says no one makes a living from olives, which were the main source of income for the people of Rameh for generations. “If anybody is still selling olives today it’s marginal income, and only a few people continue to harvest, for their own families only. Some of the agricultural land was expropriated in 1948; some was sold to the [Druze] people of Beit Jann and other communities; large tracts were split up among brothers. Today almost everybody works at something else, and for most people it’s not worth losing a work day to deal with the olives.

In Rameh, Halaf says, unlike other villages in the region, there are no more farmers. “That’s not sad, that’s the price of progress. You can’t go back, even if life then seems simpler and more pleasant,” he adds.

Perhaps The Times’ stubborn refusal to correct the plain falsehood that Rameh is Palestinian reflects the paper’s nostalgia for a time before Israel, when life was simpler and more pleasant.

In The Times’ preferred narrative, a Middle East without Israel is “smooth and doesn’t burn,” just like Rameh’s special olive oil.

See also: “Flushing the Israel Out of Ancient Israel“