- 381

- 387SHARES

For the past several weeks, the fate of Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi Arabian Muslim Brotherhood supporter who wrote for The Washington Post, has featured quite prominently in American headlines. The Saudi government, promising an investigation, belatedly acknowledged that evidence indicated that governmental officials murdered Khashoggi in a “premeditated” operation.

The news of Khashoggi’s killing was met with an uproar in the American media. Much later, and buried in a Dec. 22, 2018 article, The Post revealed that “text messages between Khashoggi and an executive at Qatar Foundation International show that the executive, Maggie Mitchell Salem, at times shaped the columns he submitted to The Washington Post, proposing topics, drafting material and prodding him to take a harder line against the Saudi government.” The newspaper also acknowledged that Khashoggi “appears to have relied on a researcher and translator affiliated with the organization.” Further, as the Security Studies Group, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, noted: “We heard from reliable sources familiar with the investigation [into his death] that documents showing wire transfers from Qatar were found in his apartment in Turkey,” but were “immediately put out of reach by Turkish security services, so they did not show the collusion between Khashoggi, Qatar, and Turkey prior his death.” Whether or not Khashoggi was an asset of Qatar, a Saudi enemy and supporter of terror groups like Hamas, The Post’s inability to properly vet his submissions and to tell the full truth about the columnist, reflects poorly on the newspaper. It is standard practice for submissions to be both original and for columnists to disclose conflicts of interest.

The news of Khashoggi’s killing was met with an uproar in the American media. Much later, and buried in a Dec. 22, 2018 article, The Post revealed that “text messages between Khashoggi and an executive at Qatar Foundation International show that the executive, Maggie Mitchell Salem, at times shaped the columns he submitted to The Washington Post, proposing topics, drafting material and prodding him to take a harder line against the Saudi government.” The newspaper also acknowledged that Khashoggi “appears to have relied on a researcher and translator affiliated with the organization.” Further, as the Security Studies Group, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, noted: “We heard from reliable sources familiar with the investigation [into his death] that documents showing wire transfers from Qatar were found in his apartment in Turkey,” but were “immediately put out of reach by Turkish security services, so they did not show the collusion between Khashoggi, Qatar, and Turkey prior his death.” Whether or not Khashoggi was an asset of Qatar, a Saudi enemy and supporter of terror groups like Hamas, The Post’s inability to properly vet his submissions and to tell the full truth about the columnist, reflects poorly on the newspaper. It is standard practice for submissions to be both original and for columnists to disclose conflicts of interest.

What was initially wall-to-wall coverage of Khashoggi’s murder vastly exceeded that of any of the other 42 journalists who were killed in the line of duty worldwide in 2017. While some of those were killed by crossfire in conflicts, others were, like Khashoggi, allegedly murdered for their work.

It’s worth asking what accounts for the discrepancy between the coverage of Khashoggi and the coverage of any other journalist who has been killed. American journalists seem to have considered Khashoggi one of them due to his work for The Washington Post. But how did he become one of them? While certainly no one deserves the fate that appears to have befallen Khashoggi, and there is no justification for the alleged actions of Saudi officials, it’s still worth asking who Khashoggi was and what he was doing writing for the Post to begin with.

Writing in Spectator USA, Matthew R.J. Brodsky of the Security Studies Group, reports that:

In the 1970s [Khashoggi] joined the Muslim Brotherhood, which exists to rid the Islamic world of western influence. He was a political Islamist until the end, recently praising the Muslim Brotherhood in the Washington Post. He championed the ‘moderate’ Islamist opposition in Syria, whose crimes against humanity are a matter of record. Khashoggi frequently sugarcoated his Islamist beliefs with constant references to freedom and democracy. But he never hid that he was in favour of a Muslim Brotherhood arc throughout the Middle East. His recurring plea to bin Salman in his columns was to embrace not western-style democracy, but the rise of political Islam which the Arab Spring had inadvertently given rise to. For Khashoggi, secularism was the enemy.

He had been a journalist in the 1980s and 1990s, but then became more of a player than a spectator. Before working with a succession of Saudi princes, he edited Saudi newspapers. The exclusive remit a Saudi government–appointed newspaper editor has is to ensure nothing remotely resembling honest journalism makes it into the pages.

As the writer Petra Marquardt-Bigman relays in Haaretz, moreover, Khashoggi kept close company with Azzam Tamimi, a Hamas promoter who has praised suicide bombings. And in 2014, during Operation Protective Edge, Khashoggi himself described “smuggling 7 metre-long Grad rockets” into Gaza as “a miracle.” He praised the “distinguished combat performance of [Gaza’s] men and the huge network of tunnels that extends for miles under Gaza and the borders with Israel and Egypt,” saying they “were used brilliantly.” Hamas, he said, “wasted no time while ruling in Gaza.”

Why on earth would The Washington Post give a platform to someone who glorified violence like that?

Perhaps it was because, at a time when the US was moving away from the JCPOA and President Trump and Israel were growing closer to the Saudis, Khashoggi provided a veneer of legitimate insider criticism of the Saudi regime. As Middle East analysts Michael Doran and Tony Badran wrote, “in presenting himself to his American friends, Khashoggi fashioned himself less the Islamist and more the democratic reformer. He made a tactical alliance with former Obama officials who seek to depict Trump’s pro-Saudi and anti-Iranian policy as a disaster.”

With his apparent murder, therefore, as Lee Smith, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, wrote:

It should come as no surprise that the Obama echo chamber used the Khashoggi affair as an opportunity to sound its anti-Saudi talking points. As a Saudi voice critical of MBS, Khashoggi’s work at the Post was integrated into the echo chamber’s anti-Saudi and pro-Iran messaging campaign. How much is U.S. reporting and opinion regarding the Khashoggi affair shaped by the pro-Iran echo chamber? Nearly all of it.

Doran and Badran concur: “Given the opposition of former Obama officials to Trump’s strategy, they have an interest in stoking outrage at Khashoggi’s death. Their goal is to harness it in order to resurrect Obama’s outreach to Tehran.”

If the American media had shown more concern over the apparent murders of, for example, six journalists in Mexico in 2017, or an American journalist in Turkey in 2014, the outrage over Khashoggi might have been viewed less cynically.

Other media responses are also noteworthy. Qatari-backed Al Jazeera, for example, unsurprisingly took the opportunity to pile on to its regional rival, with a headline asking, “Is the global response to Khashoggi killing tough enough?”

One outlet in particular seems to have completely lost the plot. Not content with providing wall-to-wall coverage of Khashoggi’s murder—some of which uncritically repeated unverified strategic leaks by the anti-Saudi Turkish government—The Washington Post saw fit to publish an Op-Ed by the leader of an antisemitic, anti-American, Iranian-backed militia.

On November 8, The Post published a piece by Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, the head of the Iran-backed Supreme Revolutionary Committee. The Houthis are currently waging a war in Yemen, fighting against a coalition led by Saudi Arabia.

On November 8, The Post published a piece by Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, the head of the Iran-backed Supreme Revolutionary Committee. The Houthis are currently waging a war in Yemen, fighting against a coalition led by Saudi Arabia.

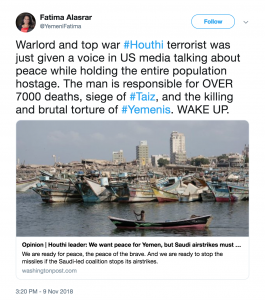

Fatima Alasrar, a Yemeni analyst for the US-based Arabia Foundation, called al-Houthi a “warlord” and “top terrorist.” On Twitter, Alasrar claimed that he was responsible for more than 7,000 deaths. She also accused him of complicity in the torture of Yemenis.

The Houthi regime also has a track record of targeting journalists. Earlier this year, for example, the Committee to Protect Journalists “called on the UN Security Council to investigate the case of a Yemeni journalist who died from torture while detained by Houthi rebels, according to Nabil Alosaidi, co-chair of the Yemeni Journalists Syndicate.”

The Houthi motto—“Death to Israel, Curse the Jews”—is openly antisemitic, as The Jerusalem Post noted. The Washington Post was widely “slammed” for its decision to publish the Op-Ed, as The Jerusalem Post’s Seth Frantzman documented.

The National, a U.A.E-based publication, said that Karen Attiah, The Washington Post’s global opinions editor, defended the paper’s decision to publish the Op-Ed. Attiah claimed that her publication has “given space to Saudis, Emiratis, Qataris, Turks, Iran… all sides of many of these debates roiling the region.” The Post, she claimed, had an obligation to publish all viewpoints—including the “abusive ones.”

Yet, it is undeniably hypocritical for The Washington Post—which has published editorials decrying rising antisemitism and dangers facing the press, and which expressed so much outrage over Khashoggi’s alleged murder—to give a platform to such a leader. One New York-based Yemeni activist, Summer Nasser, exclaimed: “How can The Washington Post allow a Houthi that kills thousands of Yemenites and silences journalists by killing them, to write an Op-Ed?” Al-Houthi’s piece, without any apparent consciousness of the irony, condemned Kashoggi’s murder. It’s also especially troubling that the Post would give al-Houthi a platform to preach about peace without reminding readers that the proximate cause of the current war was his group’s toppling of the Yemeni government in 2015.

But The Post remained blissfully unaware of the contradictions—even publishing a November 11 editorial blaming Israel for “throwing a lifeline” to the Saudi government after Khashoggi’s murder. Israel, The Post claimed, “has a long history of cultivating nasty dictators.” What the paper failed to mention: those “nasty dictators” are Israel’s neighbors; no other country in the Middle East can be considered a freedom-loving Western-style democracy. Israel does not have the luxury of having Canada and Mexico on its borders. Instead it has to “choose” between authoritarian Arab rulers who are increasingly accepting of the Jewish state’s right to exist, and pro-Iranian elements—like the Houthis—that seek its destruction. Further, The Post failed to substantiate its claim that Netanyahu was throwing a “lifeline” to the Saudi government. The paper merely noted that both the Israeli government and the Saudis have a good relationship with the White House—hardly a “lifeline.”

As stated above, none of this is to say that Khashoggi’s alleged murder was justified, or that the Saudis aren’t committing other grave human rights abuses, such as the jailing of Israa al-Ghomgham. Al-Ghomgham is currently awaiting trial in Saudi Arabia’s secretive terrorism court for protesting, in 2011, against discrimination faced by the Kingdom’s Shia minority. She faces possible beheading. The fact that, unlike Khashoggi, al-Ghomgham has a trial coming up won’t make a difference if it’s a kangaroo court.

To be sure, some increase in coverage of al-Ghomgham’s case does seem to have already resulted from the Khashoggi affair (including in The Washington Post). Similarly, there is a new interest in Turkey’s jailing of journalists. Perhaps Khashoggi’s death will inspire more coverage of other abuses in the region, for example, threats to the press in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Iran, going forward.

(Note: This post was updated on Jan. 10, 2019 to reflect new information about Khashoggi and his ties to the Qatar Foundation.)