The “apartheid” canard is a weapon. At a 2001 conference in Durbin, South Africa, which was ostensibly a United Nations-affiliated anti-racism conference, but which Holocaust survivor and Democratic congressman Tom Lantos described as “the most sickening and unabashed display of hate for Jews I have seen since the Nazi period” — even the UN’s own High Commissioner for Human Rights, who presided over the event, admitted it was marred by “horrible anti-Semitism” — radical NGOs pushed through a declaration that prescribed “a policy of complete and total isolation of Israel as an apartheid state.”

Since then, Israel’s most implacable critics have done their best to implement that policy. In the words of Benjamin Pogrund, who was an anti-apartheid journalist in South Africa and a friend of Nelson Mandela, “The idea that Israel is an apartheid state is a staple of the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement, which has made the South African comparison practically the lingua franca of anti-Israel activism.” (Those leveling the charge, he added, are “cynical and manipulative.”)

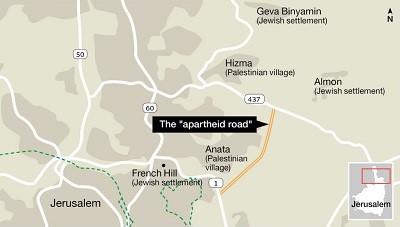

So it is no surprise that Israel’s opening of Route 4370, a strange road that’s half highway and half territorial boundary, was used as an occasion to yet again unholster the apartheid slur. The newly opened road is essentially a pair of parallel highways, one primarily serving Israeli citizens and the other serving residents of the Palestinian Authority, that are adjacent to each other but divided by a wall to ensure the security of Israelis who have been targeted in frequent spurts of Palestinian violence. The road and the wall are part of a complex division between two antagonists who have yet to agree on where a border between Israel and a future Palestinian state might run. (Jan. 18 clarification: Israelis who want to bypass Jerusalem can use the “Palestinian” side of the road, and Palestinians with a permit to enter Jerusalem are able to use the “Israeli” side of the road.)

So it is no surprise that Israel’s opening of Route 4370, a strange road that’s half highway and half territorial boundary, was used as an occasion to yet again unholster the apartheid slur. The newly opened road is essentially a pair of parallel highways, one primarily serving Israeli citizens and the other serving residents of the Palestinian Authority, that are adjacent to each other but divided by a wall to ensure the security of Israelis who have been targeted in frequent spurts of Palestinian violence. The road and the wall are part of a complex division between two antagonists who have yet to agree on where a border between Israel and a future Palestinian state might run. (Jan. 18 clarification: Israelis who want to bypass Jerusalem can use the “Palestinian” side of the road, and Palestinians with a permit to enter Jerusalem are able to use the “Israeli” side of the road.)

Some Palestinian officials quickly conflated citizenship and race. “This is an Israeli example of apartheid and racist separation that once existed in South Africa,” a PLO Executive Committee member insisted, never mind that the Israeli side of the road is accessible to Arab, Jewish, white, and black citizens of Israel, as well as to non-Israeli Arab residents of Jerusalem.

Activists weren’t the only ones to level the apartheid canard, though. A report in Haaretz about the opening of the road seemed overeager to embrace the anti-Israel charge, repeatedly using “apartheid” as a synonym for the officially named Route 4370. According to an online headline, “New ‘Apartheid Road’ Opens Separating Palestinians and Jewish Settlers.” Likewise in print, a subhead reads: “‘Apartheid road’ is divided by a barrier into separate lanes for settlers and W. Bank Palestinians.”

Most bizarrely, a map on the Haaretz website shows the location of the road alongside a label that matter-of-factly calls it “The ‘apartheid road.’”

To be sure, it is reasonable for a reporter to describe reactions to the road. Haaretz’s explanation, in the text of the article, that the highway “has been called the ‘Apartheid Road,’” is, notwithstanding the passive voice, straightforward news reporting. Israel’s critics have indeed said that.

But as the text of the article makes clear, there is another side to the discussion, where proponents of the road call it other things: An “oxygen line for the region’s residents.” A road that succeeds at “solving traffic congestion problems.” A “true blessing.” And “an example of the ability to create a common life between Israelis and Palestinians.”

And even critics of the highway have acknowledged that it was designed to help Palestinians travel between cities without interruption. The Jerusalem Post notes,

According to the left-wing NGO Ir Amim, the road was initially conceived by former prime minister Ariel Sharon to address the main international complaint with regard to the E1 project – namely, that it interrupted Palestinian contiguity in the West Bank.

The new road provides Palestinians with a direct access point between Ramallah and Jerusalem.

Again, the issue with Haaretz’s coverage isn’t that it reports what critics have said. It’s that the newspaper, with its headlines and illustrations, is clearly joining forces with those critics, adopting their allegations and using what amounts to product placement to helping to sell their inflammatory language.

Haaretz could have just as well titled its piece, “New ‘anti-congestion road’ opens.” On its map, the highway could have been labeled “The ‘contiguity’ road.” If that were the case, Haaretz might be seen as siding with the proponents of Route 4370. As it stands, the paper is clearly siding with the road’s opponents. That’s an acceptable position for a newspaper to take — but on the opinion pages. When the news is dressed up like an Op-Ed, a newspaper loses its claim to impartiality.

The New York Post‘s coverage of the road, meanwhile, was based directly on Haaretz’s report, but managed to be even more lopsided.

For example, the Haaretz piece explained:

The road was built over a decade ago but remained closed due to a dispute between the army and the police over the staffing of a new checkpoint.

But the Post reporter, Yaron Steinbuch, put it this way:

“Apartheid Road,” which was built more than 10 years ago, remained closed amid a dispute between the Israel Defense Forces and the country’s police in connection with a new checkpoint.

Steinbuch confuses synonyms and slurs, using the anti-Israel talking point as if it were a straightforward way for an objective news reporter to refer to the highway. The anti-Israel activists at the 2001 Durban conference would be pleased.

And while Haaretz at least hinted at the reason a protective barrier might be needed by quoting an Israeli minister who referred to “security concerns,” the Post omitted any reference to Israeli security, or the violence that has targeted Israeli civilians.

Neither report offered readers the context that appeared in an article by Agence France Press, which explained that when the Israeli minister referred to security, he “was referring to Palestinian attacks against Israelis, which in recent years have included sometimes deadly car-rammings and stabbings.”

And AFP’s story, unlike its counterparts, also avoided treating the Palestinians like a monolith. It reported on criticism from Palestinians. And it also quoted a Palestinian who found the road advantageous, since it “cut his journey to the neighboring village of Anata to a few minutes instead of half an hour or more.”