- 369

- 382SHARES

DEC. 14 UPDATE:

CAMERA Prompts Editors' Note

As a result of CAMERA's research and correspondence with editors, the New York Times has published a forceful editors' note effectively retracting the article's core premise. The note acknowledges that the article didn't accurately reflect the subject of the piece, and suggests that more extensive reporting was necessary. See below for a detailed update.

In the New York Times this month, reporter Patrick Kingsley tells a tale of a Gaza poetry professor who breaks down boundaries.

Professor Refaat Alareer, readers are told, “add[s] nuance” to the contrasting narratives of Palestinians and Israelis. He offers students “an appreciation” of Israeli poets. He admires the way an Israeli poet blurs divisions between the two sides. In spite of his hardships — imposed by Israel — Alareer is a surprising “champion” of Israeli poetry, who uses poems to teach about the “humanity” of Israeli Jews.

It’s lovely. It’s unexpected.

But it’s fiction.

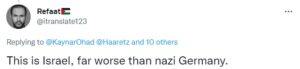

On social media, Alareer reveals himself as a man overflowing with hate. One might call his relentless slurs puerile — “Zionists are dumb”; “to be a Zionist is to be a heartless twat and a piece of shit”; “Zionists are the ugliest, unfunniest, and most untalented people on the globe” — but to evoke childishness, as that word does, would be to gloss over dangerous bigotry and dehumanization.

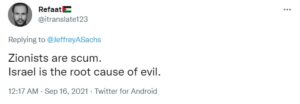

“Zionists are scum,” he insists.

“Zionists are the most despicable filth.”

“Zionism is a disease.”

He is undeterred by the fact that, to antisemites, “Zionist” is a euphemism for Jew. He is undeterred, too, by the fact that to Jews, the Z-word refers to the majority of Jews worldwide. (In the U.S. alone, over 8 in 10 Jews say caring about Israel is essential or important to their Judaism.) He is even undeterred by the fact that the Nazis famously described their Jewish victims as filthy, subhuman, viruses — a form of dehumanization believed to be a precursor to genocide.

Perhaps Alareer doesn’t consider how his language evokes that of the Third Reich because he is too busy comparing the Jewish state and its supporters to Nazis. Israel is “far worse than nazi Germany,” reads one of his Twitter posts. “Israel is nazism on steroid,” reads another. “Israel is heir to nazi Germany.” There is a “nazi-like occupation of Palestine.” “Israel had always embraced nazism, nazis, and neo-nazis.” “Israel is using Nazim to do to Palestinians what the Nazis did.”

Perhaps Alareer doesn’t consider how his language evokes that of the Third Reich because he is too busy comparing the Jewish state and its supporters to Nazis. Israel is “far worse than nazi Germany,” reads one of his Twitter posts. “Israel is nazism on steroid,” reads another. “Israel is heir to nazi Germany.” There is a “nazi-like occupation of Palestine.” “Israel had always embraced nazism, nazis, and neo-nazis.” “Israel is using Nazim to do to Palestinians what the Nazis did.”

A widely adopted IHRA working definition of antisemitism might describe such rhetoric — “drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis” — as an example of antisemitism. But rest assured, Alareer does not care: “shove the ihra & its racist definition up your arse,” he has mused.

Historian Deborah Lipstadt might argue that Holocaust inversion, a term used to describe the charge that Israel behaves like the Nazis, is a form of “soft-core [Holocaust] denial” that “elevates by a factor of a zillion any wrongdoings Israel might have done, and lessens by a factor of a zillion what the Germans did.” But Alareer doesn’t hesitate to suggest that anything and everything is proof of Israeli Nazism.

Israel’s delivery of Covid vaccines to the Palestinian Authority? That’s Nazism: “Israel is a brutal nazi-like entity,” he wrote shortly after Palestinian medical authorities received the vaccines. “[I]t sent EXPIRED vaccines to Palestinians to further worsen the covid19 pandemic.” (The claim that the vaccines were expired and dangerous was, like so much antisemitic rhetoric, a flagrant lie.)

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand how Alareer’s slurs about Jews and the Holocaust are a spit to the face of Holocaust survivors, so many of whom he casts as Nazis when he revoltingly states, for example, that “all supporters of Israel would be cheering for the Nazis in the 30s and 40s.”

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand how Alareer’s slurs about Jews and the Holocaust are a spit to the face of Holocaust survivors, so many of whom he casts as Nazis when he revoltingly states, for example, that “all supporters of Israel would be cheering for the Nazis in the 30s and 40s.”

And with such screeds, he reminds us again that the target of his Holocaust inversion isn’t only Israel, but also the majority of Jews worldwide who support its existence.

“Zionists are Nazi criminals.”

Zionists are “heirs of nazis.”

“The Zionists learnt well from the Nazis, so well.”

“It was the marriage between Nazis and Zionists that gave birth to the most hideously abhorrent offspring, Israel.”

“[Z]ionism is nazism … and it does turn ‘humans’ into absolute bigots.” (Note the scare quotes around “humans.”)

More often, Alareer uses “Zios,” a term linked to former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, and which even critics of Israel admit is an antisemitic slur.

“I can flood you with evidence of Israel being nazi and doing nazi stuff and supporting and endorsing nazis and committing nazi-like crimes,” wrote Alareer. “[B]ut no zio will change ‘its’ mind.” (Again, note the scare quotes.)

“[Z]ios are heartless brainless pieces of shit who conspired with the nazis against the jews.”

“[Z]ios are heartless brainless pieces of shit who conspired with the nazis against the jews.”

“Like Nazis, Zios will always claim to be the victims. Same shit, same asshole!”

“[H]ow do you know a zio is lying? when he opens his mouth.”

“Zios are the enemy of the free and decent people around the world.”

“Jake tapper is a zio islamophobic piece of shit.”

“Look at them zios be shitty as shit and making millions only because they are hateful and anti-Palestinian bigots, whose only qualification is Israel and hating Palestinians.”

“All zios stink.”

And, in a post that suggests the author of such elegant prose might lack self-awareness: “zios are the most uncreative shit ever.”

Alareer draw a connection between a Jewish journalist, whom he called a "Zio" and a "dirty snitch," and Jewish concentration camp inmates who, he suggests, were predisposed to becoming Kapos.

Alareer is too clever to refer directly to Jews, except to insist he has nothing against them per se. (Update: He is not.) He is quoted saying as much in the New York Times article. But some of his social media posts are revealing.

On Twitter, for example, he used his favorite slur in reference to concentration camps inmates, whose religion he would know, but whose political views he would not: “Zios are the dirtiest little snitches ever… No wonder many of them kapoed like bitches.” (The term “kapo” describes concentration camp inmates assigned to positions of power by the Nazis.)

One Friday evening, he ended a touchy exchange with a Jewish interlocutor with the salutation, “shabat shit,” a play on the traditional Jewish sabbath greeting, “Shabbat shalom.”

And in a clear reference to American Jews, Alareer wrote that “all American losers can go to occupied Palestine for free housing and the thrill to shoot and murder.”

To be fair, it isn’t only Jews that he targets. After a Palestinian journalist reported on criticism of Hamas, Alareer wrote that the article “is the result of smelling too much zio farts which must have addled his tiny brain.”

This is the man cast as a bridge-builder by the New York Times.

The article does briefly nod toward Alareer’s behavior on Twitter. The professor “frequently writes furious barrages that describe Israel as a source of evil,” Kingsley states, citing as an example a post in which the professor defends violence against Israeli civilians: “No form, act, or means of Palestinian resistance whatsoever is terror. All Israelis are soldiers. All Palestine is occupied.”

It is vile to defend terrorism. But Kingsley’s characterization, and the single example he cites, fall far short of conveying the extent of Alareer’s unhinged attacks. And at any rate, the reporter’s admission is immediately followed by an exculpatory but: “But in the lecture theater, Mr. Alareer has a milder academic approach.”

The exculpation is the point. The reference to “furious” posts on social media serves as little more than a flourish adding color to an otherwise hagiographic story. Which raises the question: Why? Why does the newspaper offer its platform to profile, laud, and rehabilitate a hatemonger whose main hobbies are poetry and slurring the mainstream Jewish community?

A generous observer might say that a fuller understanding of Alareer’s online extremism would only sharpen the article’s intriguing juxtaposition: The man who hates Israel online — a lot — but still teaches empathy for Israelis in the classroom.

Alas. The newspaper’s depiction of Alareer’s classroom conduct is a forgery. There are fewer obscenities. There are a few references to diction and meter. But his lectures on Israeli poetry are much closer to what we see from him on Twitter than what we’re told of him by the New York Times.

It is unclear whether, in this particular case of misreporting, the paper knowingly duped readers, or whether Kingsley was himself was fooled by the hero of his story. Readers aren’t informed if a reporter was present in the classroom, with Alareer’s knowledge and consent, during the purportedly moderate lecture. But photos accompanying the article reveal that he knew he was being observed, at the very least by a photographer who works with the New York Times if not by Kingsley himself.

Perhaps, then, Alareer put on a performance for Western audiences. Perhaps the Times misrepresentation wasn’t willful, but the story was just too good to check for a newspaper whose narrative so often conceals the role Palestinian extremists play in perpetuating the conflict. (Recall that a New York Times editor once felt the need to remind her colleagues that Palestinians are “more than just victims.”)

A photograph accompanying the New York Times article suggests Rifaat Alareer understood he was being observed by Western media.

Had the Times bothered, though, to “seek truth and report it” (as one set of journalistic guidelines puts it), it would have found a 2019 lecture by Alareer posted on Youtube and on his university’s website. The video shows the professor teaching the very same course unit described in the newspaper’s story, but from a couple of years earlier, on a day when there were no news reporters in the classroom.

On that day, Alareer highlighted the same Israeli poets mentioned in the Times article, Yehuda Amichai and Tuvya Ruebner, and taught their same two poems. But the message of his older lecture is the very opposite of the one the newspaper conveyed to readers.

In the New York Times, the lesson is said to serve as a “counterpoint” to the assumption that “the Palestinian education system is simply an engine of incitement.” Alareer is said to “teach Palestinians about empathy.” His curriculum is said to be an “appreciation” of the poet Yehuda Amichai. Even Amichai’s family, seemingly having been appraised by Kingsley, is said to be “inspired” by the professor’s “use of poetry to see the humanity on the other side.”

Here, though, is what Alareer himself said about Amichai's work during the 2019 lecture: “This is a horrible, horrible poem.”

The poem is “dangerous,” he tells students.

“This is some kind of colonial literature, it brainwashes, it presents the Israelis as innocent,” he said. “They’re not innocent ….”

The poem peddles “alternative facts,” he continues. It “does damage to Palestine, to Palestinians.” It is an “ideological tool” and so largely “loses its poetic value.” And so on.

Per the New York Times account,

What Mr. Alareer admired about [Amichai’s] poem, “Jerusalem,” he told his students, was the way it blurred divisions between Israelis and Palestinians and implied that “Jerusalem can be the place where we all come together, regardless of religion and faith.”

“When I read this,” he added, “I really was like, ‘Oh my god, this is beautiful. I’ve never seen something like this. I never thought that I would read it.’ And then I realized: No, there are so many other Israeli people, Jewish people, who are totally and completely against the occupation.”

But in his 2019 lecture, Alareer says something very different. Far from admiring “blurred divisions,” he demands his students not be seduced by the poem’s elegance: “It presents the Israeli occupation as innocent, you know, the victim. Never, never bring the occupied and the occupier, the colonized and the colonizer, the oppressed and the oppressor, in the same scale.” (Recall that, to Alareer, “the occupation” describes Israel’s existence within any boundaries: “All Palestine is occupied.”)

The lecture is often incoherent in its indictments of Israel's poetry. In one breath, the professor charges Amichai with “dehumanizing” and “alienating” Palestinians. In the next he insists the poem is “dangerous” precisely because it “presents people as equal” and the Palestinians as “human.”

Does he find the poem “beautiful,” and did it help him realize there are Israelis and Jews can be his allies, as he’s quoted saying in the lecture observed by the Times? Again, the opposite is be true. “While this is a beautiful poem from an aesthetic perspective, this is a horrible, horrible poem,” he said in his 2019 lecture, “because this is a tool of further demonizing Palestinians, further dehumanizing Palestinians, and presenting Palestinians as, as uncivil, as uncivilized, as the enemy.” (It is a bizarre interpretation of the poem, as we’ll see below.)

Alareer directs students to similar conclusions about Tuvia Ruebner and his poem “There, I said,” the other example he discusses in class. Ruebner, too, is guilty of fabricating history. His poem, too, is cast as “dangerous” and an “ideological tool.” It “erases,” “annihilates,” and “eradicates” Palestinians. Its verses are a fabrication. It is “in part to blame for the ethnic cleansing and destruction of Palestine.” (Again, as we’ll see below, this interpretation is bewildering.)

Empathy? To analyze the poem, Alareer tells the class, you have to put yourselves in Ruebner’s shoes — but then “you have to endure the stink, of course.”

The poetry professor leaves no room for imagination: “I hate [this] kind of poetry,” Alareer says.

So much for being a surprising “champion” of Israeli poetry. The entire lesson on Israeli poetry, in fact, is framed from the start as one about the dark side of the art, a departure from what poetry can and should be. Here is how Alareer opens his lecture:

So far we spoke about the thrilling aspects of poetry, how poetry transcends us, how poetry breaks the barriers and the boundaries and pushes the boundaries, you know all these clichés we use to talk about how the aesthetic values of poetry how poetry helps and contribute to the advancement of human thought and civilization, how poet changes people, how poetry unites us brings us together….

However, poetry has also been used as a tool. A weapon, by totalitarian regimes, by colonizers.

The lessons Alareer seeks to impart aren’t only about the poets themselves. “[T]he problem with the Zionists, uh, Zionists in general is that– many problems, actually,” he tells students. Jews living in Jerusalem are “occupiers,” “intruders,” and “aliens.”

“Those liberal Zionists,” he tells the class later, “are very dangerous. They don’t oppose the occupation, he alleges. “They just want a cute occupation, an occupation that would kill Palestinians not by massacring and bombing them, but by probably starving them, besieging them, you know, or by, or if you kill them kill them off camera, off stage, because you’re making us look bad in the West.” In other words, most Jews are murderers.

“Those liberal Zionists,” he tells the class later, “are very dangerous. They don’t oppose the occupation, he alleges. “They just want a cute occupation, an occupation that would kill Palestinians not by massacring and bombing them, but by probably starving them, besieging them, you know, or by, or if you kill them kill them off camera, off stage, because you’re making us look bad in the West.” In other words, most Jews are murderers.

So much for showing “the humanity on the other side.”

The professor doesn't only express hatred of Amichai and Ruebner. He also flagrantly lies to students about the meaning of their poems, and the disconnect between his “analyses” and the actual poetry serves as the most conclusive evidence that Alareer’s goal isn't to educate students, who are certain to emerge from the hour more ignorant than when they started, but rather to demonize and incite.

Consider his interpretation of Yehuda Amichai’s “Jerusalem.”

On a roof in the Old City

Laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight:

The white sheet of a woman who is my enemy,

The towel of a man who is my enemy,

To wipe off the sweat of his brow.

In the sky of the Old City

A kite.

At the other end of the string,

A child

I can’t see

Because of the wall.

We have put up many flags,

They have put up many flags.

To make us think that they’re happy.

To make them think that we’re happy.

“Jerusalem” was written prior to 1967, at a time when its namesake city was divided by barbed wire, split between Israel in its western half and the Kingdom of Jordan in its eastern half. The poem describes an Israeli sitting on the roof of his home, gazing across the divide at fluttering objects belonging to those he can’t see “because of the wall” that divides the Jewish and the Arab side. There is laundry, a sheet, a towel, and a kite whose young owner is concealed from view. The poem concludes with a comment on the “many flags” put up by the two sides — that of Amichai and that of the “enemy” — flags that make each side believe they are happy, the poet writes.

When Times-affiliated journalists were in the room, Alareer praised the poem, saying he was touched by how it humanizes adversaries and shows that “Jerusalem can be the place where we all come together, regardless of religion and faith.” But in a more typical classroom setting, he reviles the poem as one that “dehumanizes” Palestinians.

We might trust the former version, which, after all, he told while under outside observation. And indeed, this is the view most subscribe to, including Lobna Ben Salem, now a professor of comparative literature at a University of Manouba in Tunisia, who cited “Jerusalem” as an example of Amichai’s “poetic egalitarianism that aspires for peaceful coexistence of the Arab and Israeli.”

The kindest view would be that poetry is subject to interpretation — even outlandish ones. (In his 2019 lecture, Alareer bizarrely insists Amichai's poem is proof that, in contrast with Palestinians who see Jerusalem as a spiritual place that connects them to their ancestors, Israeli Jewish “aliens” in Jerusalem see only minutia, like laundry and walls, or thread and buttons. “Yeah, so what does this man see in Jerusalem?” he asks the class. “The laundry, the laundry, the laundry,” he answers sarcastically. “You go to Jerusalem to look at people's laundry. Okay.”)

The kindest view would be that poetry is subject to interpretation — even outlandish ones. (In his 2019 lecture, Alareer bizarrely insists Amichai's poem is proof that, in contrast with Palestinians who see Jerusalem as a spiritual place that connects them to their ancestors, Israeli Jewish “aliens” in Jerusalem see only minutia, like laundry and walls, or thread and buttons. “Yeah, so what does this man see in Jerusalem?” he asks the class. “The laundry, the laundry, the laundry,” he answers sarcastically. “You go to Jerusalem to look at people's laundry. Okay.”)

What isn’t debatable, though, is the circumstances of the city at the time Amichai’s poem was written — circumstances clearly reflected in the verses themselves. A few years earlier, the Kingdom of Jordan invaded and conquered the eastern half of the city and expelled its Jewish residents. Part of the ceasefire line dividing the sides ran along the centuries-old walls of the Old City. And in the early 1960s, Amichai lived in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Yemin Moshe, which abutted the dividing line and the Old City walls.

In his 2019 lecture, though, Alareer doesn’t tell students when the poem was written, or more importantly, what that means. Instead, he leads them to believe the wall in Amichai's poem is the security barrier Israel built to deter suicide bombers so many decades after the verses were written.

“There are many walls in Jerusalem,” Alareer says. “Some of them are very historical, very ancient, [and] some of them Israel built.” And the wall in Amichai’s poem, Alareer repeats to his class, is the one Israel built. “It’s not like, ‘Ah, there’s a wall here, we can’t see each other, we can’t communicate, we can’t speak. … [T]his is again how alternative facts are offered. Israel caused this. Israel built the wall.” It didn't.

Why does Alareer mislead students, misrepresent the sympathetic and self-critical Amichai as a monster, and twist everything into an anti-Israel lesson? Because he is not a bridge-builder. The professor is, at his core, the same man who spews hate on online. His classroom behavior perhaps differs from his Twitter tantrums in tone, but certainly not in content.

His analysis of the other poem, “There, I said,” by Tuvia Ruebner, likewise misleads for the sake of indoctrinating students against all Israelis.

I set out from my temporary home to show my children where I came from.

There, I said, I lay on the ground

a stone for a pillow, my head lower than the grass

like the dust of the earth

everything is preserved there.

We passed mountains and forests that were

caves, and water collected in pools along the way and the roads were bad.

The car lurched over the ditches

What is this sweet air? my children ask.

What is that plaster falling from the walls?

It’s nothing, said the old woman in the window.

Here, also the future is past. And she closed her dry eyes

Like a bird that flies high, then folds its wings and dives.

I was born here, I told my children.

My parents and ancestors were born nearby.

Everyone is born. Here was a house

I told my children and the wind passed

between me and the words.

I set out to show my children where I came from, and when

will we eat, they asked, and where

will we sleep?

The poem is about a man who travels from what he calls his temporary home in order to show his sons the place he came from.

“The temporary home,” Alareer claims in his 2019 lecture, “refers to [Ruebner's] home in Europe.” And by the place he came from, Alareer continues, the poet “means Palestine—he doesn’t mean Slovenia or Slovakia.” In short, students are told, the poem is about a “brainwashed” Jewish parent trying to indoctrinate his children into believing that Palestine, the Land of Israel, is their homeland.

But this, he insists, “is a fabrication.” Jews aren’t from Palestine, he argues. Even ancient Jews living in the ancient land of Israel aren’t really from there. They “came from different geographical places” to join the Canaanites. The are “immigrants.”

“That’s why I hate such kind of poetry,” Alareer continues.

“When a Jewish poet says everything has been preserved,” he tells students, “this is a fabrication of history, this goes against history.”

To punctuate the point that Ruebner is a liar, Alareer alternates between lines from the poem and his rebuttal:

“I was born here” – he wasn't! But again, he is erasing 2,000 years of history. “I was born here” — no, you were born in Europe. “And my parents my parents my grandparents were born nearby.” Yeah if nearby if Russia is nearby, or Slovakia, or, what's the country?

The country, it turns out, is indeed Slovakia.

Ruebner often writes about Israel. And notwithstanding Alareer’s false claim that such Israeli poets depict Palestinians as “savages” who "want somebody … to kill them, to kick them out, to civilize them, to send them out of Palestine,” Ruebner's poems are often virulently critical of his government and sympathetic to Palestinians.

But this particular poem isn't about Israel or the Palestinians. Contrary to everything Alareer tells his students, it is broadly understood as a poem about a Jewish man's return visit to Europe some years after the Holocaust, a voyage meant to convey something of the past to the next generation.

Ruebner was born in Slovakia. He moved to what is now Israel just as the slaughter in Europe began. His parents and sister, who remained in Europe, were murdered in Auschwitz. Much of Ruebner's poetry focuses on this loss. And although Zionism saved his life, he is far from the nationalist "tool" — or the “genocidal” “mass murder” — that Alareer claims him to be. “I feel that I have two ‘no-homelands,’” Ruebner once said. “I was uprooted twice. A person can have only one homeland: the place where he was born. Slovakia spewed me out and what is happening in Israel today has uprooted me again.”

None of this matters to Alareer. He lies about Ruebner and the content of his poem because he says what he has to say to demonize Jews.

Nor, apparently, does any of this matter to the New York Times. Despite publicly available evidence to the contrary, the newspaper treats Alareer an archetype of a noble professor—a scholar who seeks the truth despite his surroundings, and despite even his own anger outside the classroom. As the newspaper’s subhead puts it: “On social media, Refaat Alareer rages against Israel. In the lecture hall, he studiously analyzes the work of some of its leading poets — and surprises some of his students.”

This is a falsehood in league with Alareer's own lies. In a typical teaching year, there is no “studious analysis” of Israel. There is no “nuance,” or “appreciation,” or “championing,” or teaching of “humanity.” There is just more rage.

We know why Alareer does what he does. Online and in class, he hopes to spread the idea that “Zios” are “scum,” “filth,” “disease,” and “the enemy of the free and decent people around the world.”

And we know why he’s employed to do so by the Islamic University of Gaza. Even the New York Times once admitted that the school is “one of the prime means for Hamas to convert Palestinians to its Islamist cause.”

But why do Kingsley and the New York Times go out of their way to cover up for Alareer, to the point where they — much like the professor they defend — egregiously mislead their audience? To those who expect truthful journalism from the newspaper, that is the real surprise.

Read also: "Does the New York Times Have a Problem Recognizing Antisemitism."

See also: CAMERA's video shows Alareer's classroom incitement.

Update: New York Times Corrects

After CAMERA informed New York Times editors of Alareer's history of demonizing and misrepresenting Israelis in the classroom, which was essentially the opposite of what the paper had portrayed, the newspaper published the following editors' note:

Editors’ Note, Dec. 13, 2021:

After publication of this article, Times editors reviewed additional information that is at odds with the article’s portrayal of Refaat Alareer, a literature professor at Islamic University in Gaza, who was described as presenting Israeli poems in a positive light to his Palestinian students.

In the class witnessed by a Times reporter, Mr. Alareer taught a poem by the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, which he called “beautiful,” saying it underscored the “shared humanity” of Israelis and Palestinians. He said he admired how it showed that Jerusalem is a place “where we all come together, regardless of religion and faith.”

However, in a video of a class from 2019, he called the same poem “horrible” and “dangerous,” saying that although it was aesthetically beautiful, it “brainwashes” readers by presenting the Israelis “as innocent.” He also discussed a second Israeli poem, by Tuvya Ruebner, which he called “dangerous,” adding “this kind of poetry is in part to blame for the ethnic cleansing and destruction of Palestine.”

When The Times asked Mr. Alareer about the discrepancy, he denied that there was a “substantial change” in his teaching and said that showing parallels between Palestinians and Jews was his “ultimate goal.” But he said that Israel used literature as “a tool of colonialism and oppression” and that this raised “legitimate questions” about Mr. Amichai’s poem.

In light of this additional information, editors have concluded that the article did not accurately reflect Mr. Alareer’s views on Israeli poetry or how he teaches it. Had The Times done more extensive reporting on Mr. Alareer, the article would have presented a more complete picture.

We commend editors for forthrightly acknowledging and updating readers about the serious problems with its piece. We hope future stories about the conflict will be more carefully researched, and that facts will matter more than narrative.

For the Arabic version of this post, please see CAMERA Arabic.