- 2.8K

- 2.8KSHARES

For those concerned about anti-Jewish violence in America, 2019 will be remembered as the year Jews were shot in a synagogue, slashed at a Hannukah party, and assaulted daily on the streets of New York.

And for those who understand that the violence was inspired by antisemitism, and that the normalization of this hateful worldview will increase the risk to innocent Jews, 2019 might also be remembered as the Year of the Dog.

The dog, in this case, appeared in a political cartoon published by the New York Times. It was drawn with the face of Israel’s prime minister and was depicted leading a blind President Trump. A Star of David dangled from the dachshund’s collar and, to avoid ambiguity about what the star represented, a kippah rested on Trump’s head. The power wielded by the Jewish leader of the Jewish state is depicted as so complete, in other words — and so, well, Jewish — that he managed to turn our Presbyterian president into a Jew.

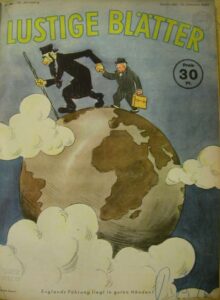

The cartoon’s message of Jewish control over world governments is familiar to Jews, and to those who hate us, because it’s an old trope. Printed on the cover of a 1940 issue of the German magazine Lustige Blätter, for example, is a caricature of a religious Jew leading an enfeebled Winston Churchill by the hand, with the Jew and his British instrument stomping across the globe. An ironic caption reads, “England’s leadership is in good hands.”

That illustration, at least, spared Churchill the kippah. But we don’t have to look to Nazi Germany for commentary on what the Jewish head-covering worn by the president communicates. Only a month after the Judaized Trump appeared in the pages of the New York Times International Edition, a far-right Polish politician performed the cartoon live during a televised debate by holding a kippah over the head of his political opponent. The gesture, his party colleague explained, was meant to show that the rival politician “kneels before the Jews.”

The Times atoned for its cartoon. “Such imagery is always dangerous, and at a time when anti-Semitism is on the rise worldwide, it’s all the more unacceptable,” the apology stated.

The sentiment is correct. The words are welcome. And still, there is reason to doubt the newspaper’s vigilance against the creep of this ancient hatred.

Let’s apply what might be called the Sandwich Test to the newspaper’s mea culpa. It’s simple: If the infraction you apologize for is sandwiched between additional examples of the very same thing, then it is not an isolated error of judgment, but a pattern. And in the case of the New York Times failing to recognize antisemitism and act accordingly, the paper flunks the sandwich test.

One need only look a few months prior the publication of the cartoon to encounter another example of the paper seeing anti-Jewish material, shrugging, and publishing. It was December 2018, and the New York Times turned to Alice Walker for its “By the Book” feature, a weekly interview series that promotes authors’ recent work while tossing them softball questions. (Think, “What books are on your nightstand?”)

Walker is best known for her award-winning 1982 novel The Color Purple. But she subsequently emerged as someone who, as a Vox culture writer generously put it, “has flirted with anti-Semitism for years.” A longtime admirer of Walker writing for New York Magazine was blunter, noting that Walker “had been indulging in virulent anti-Semitism, and that it permeated not just her thinking but her work.”

At best, Walker’s history of promoting antisemitism’s greatest hits — her charge that the “poisonous” Talmud condones pedophilia and rape, that the “Chosen People” have a history of oppressing non-Jews, and that the Jewish Rothschild family are puppet-masters who secretly direct global events — went unnoticed by New York Times editors. At worst, they didn’t regard this type of bigotry as disqualifying for a fluffy interview.

Either way, the interview with an antisemite had predictable results: The most influential newspaper in the U.S. published Walker’s endorsement of an unhinged book by David Icke, a conspiracy theorist whose concern about meddling Jews comes second only to his alarm over the shape-shifting lizard-people who he says populate the earth.

The book our friends and neighbors were told to read, without warning or qualification by the newspaper, promotes Holocaust denial, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and the idea that Jewish bankers rule the world. In the face of widespread criticism, editors were unapologetic.

The interview with Walker was published shortly before the cartoon about Jewish leaders who, well, rule the world. And only a few days after the cartoon, the New York Times again shrugged off antisemitism when, on Twitter, it described the murdered Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi as someone who “spoke up for others.”

Here’s how Khashoggi spoke up about certain others: “Jews aren’t desperate to deny anything as much as they deny their Protocols,” he wrote in a June 2011 Arabic tweet, in reference to the antisemitic forgery about a Jewish plot to — it’s a pattern — rule the world.

Such slurs obviously don’t justify Khashoggi’s terrible fate. But they should have disqualified him from being venerated by the New York Times as a humanitarian hero.

The pattern extends beyond those three examples. Consider the newspaper’s May 2019 report on Valerie Plame’s entry into the U.S. congressional race, where you’ll find a smiling photo of the candidate, a caption parroting her campaign materials, and not a single word alerting readers to Plame’s assertion on Twitter that “America’s Jews Are Driving America’s Wars.”

There’s no need for Talmudic analysis here. Plame was inciting hate. But as with the bigoted cartoon, the odious book recommendation, and the Saudi humanitarian’s anti-Jewish conspiracies, this particular breed of hate didn’t register with Times reporters and editors responsible for the story.

In part, the disinterest in Plame’s antisemitism might reflect the paper’s political leanings. Plame is a Democrat. And the Times is seen as favoring that party. But then there’s the case of the late Paul Findley, a Republican who, like Plame, argued that America’s Jews drive America’s wars.

A former congressman, Findley devoted his later life to attacking the “Jewish lobby” and “Israel lobby,” terms he used interchangeably because he viewed the Jews and Israel interchangeably — and unfavorably. Take, for example, the 2013 interview in which Findley, responding to a question about whether he met Israelis, told a story of being beleaguered by a “phalanx of Jews” from Illinois.

Speaking about the congressman’s relationship with PLO leader Yasir Arafat in the 1970s, the interviewer asked, “During the time you were reaching out to Arafat, were you thinking, at that time, of stopping by Israel, as well, and getting their perspective?”

“Well, I didn’t have to stop by,” Findley replied. “The rabbis in Springfield always, or seemed to always, meet my plane with lots of comments. I recall being in Chicago one day, and I had to catch a plane about an hour ahead. There was a phalanx of Jews that wanted to have my ear.”

According to Findley’s account, the brigade of rabbis dared to suggest he meet with a particular university professor. “I thought it was rather insulting,” he told the interviewer. “They were tough people.”

“They being who?”

“The Jewish community,” Findley explained. The whole lot.

Findley’s legacy vis-à-vis Jews, then, shouldn’t come as a surprise. When not arguing that Israel might be responsible for assassinating John F. Kennedy and for planning to kill George H. W. Bush, he served as a board member of If Americans Knew, a fringe organization whose founder, Alison Weir, endorses the veracity of the anti-Jewish blood libel and promotes the view that the persistence of antisemitism proves Jews bringing hatred upon themselves.

And Weir, when not appearing on white supremacist radio shows, serves as president of the Council for the National Interest (CNI), an organization co-founded by Findley. If you visit CNI’s website today, you can find articles insisting historiography about the “so-called holocaust” is “largely fabricated”; arguing that “Israel and Jewish groups…use their wealth and access to power to corrupt America’s institutions and drive the country to needless wars”; declaring that American Jewish legislators “regularly exhibit what amounts to ‘dual loyalty’”; and insisting that “Jews do control the media.”

What did The New York Times have to say about Findley’s involvement in this web of hate? The newspaper’s August 2019 obituary for Findley ignored it, and instead cast the congressman as a “moderate” truth-teller who merely “spoke out about his frustrations with the United States government’s overwhelmingly pro-Israel posture.”

(It’s not that the Times shies away from sharp words about deceased public figures. The paper’s obituary for Princeton professor Bernard Lewis, for example, turned over three paragraphs to critics who called the influential scholar a “propagandist” who “looked down on modern Arabs” and took “belligerent” positions on Islam. Findely was spared that treatment.)

With Findley (R) joining Plame (D) in the newspaper’s safe room, it is clear that party affiliation alone doesn’t explain the paper’s amnesia about antisemitism.

So what else do they have in common? What other forces are at work? How did we arrive at a place where the New York Times is guilty of journalism that is dangerous for American Jews?

Dangerous is a strong word. But it’s an apt one. The regressive opinions given a pass by the Times — the collection of anti-Jewish conspiracies preached by the cartoon, Alice Walker, David Icke, Jamal Khashoggi, Valerie Plame, and Paul Findley — are the same opinions that inspire violence against Jews.

An image shared by Pittsburgh shooter Robert Bowers depicts Donald Trump taking orders from the Jews.

Not long before he murdered 11 Jews in a Pittsburgh synagogue, for example, the neo-Nazi responsible for the slaughter shared an image depicting Jewish control over a compliant President Trump, the very notion promoted by the infamous cartoon.

The white supremacist who opened fire on worshipers in a Poway, California synagogue, meanwhile, left a manifesto blaming Jews for their “role in starting wars” (just as Plame tweeted); for their “exorbitant role in news media” (as Findley’s organizations argue); for using “banks to enslave nations in debt and control all finances” (as Icke insists); for their “role in every slave trade for the past two-thousand years” (as Walker and Icke believe); and for their “persecution of Christians” (as Walker alleges).

Again: The ideas ignored or promoted by the Times get people killed. So again: What’s behind the newspaper’s blind spot?

A particular point from the Poway shooter’s manifesto might offer a hint. In his screed about Jewish persecution of Christians everywhere, the attacker specifically mentioned Jewish-Israeli persecution of the “Christians of modern-day … Palestine.” On this point, at least, the killer’s rage is shared by all of the above figures, and by the New York Times itself.

Maybe, then, the newspaper’s coverage of Israel and the Palestinians serves as as a gateway drug — its callous treatment of the world’s largest concentration of Jews eventually extends to Jews elsewhere.

To understand how such a metastasis can happen, let’s trace a path beginning with one example from last year of the Times skewing coverage against Israel, which we visualize as Point A. During an appearance on the wildly popular New York Times podcast “The Daily” last April, Times reporter Mark Landler told listeners that Palestinians haven’t achieved independence “because, through wars and other conquests, the Israelis began to occupy more and more of the land that would form the basis for a Palestinian state.”

Such is the newspaper’s lopsided history of the Arab-Israeli conflict. There’s no Palestinian rejection of statehood in 1947. No Jordanian and Egyptian occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. No threat to Israel in 1967. No Arab commitment to destroy Israel in the decades that followed. No Palestinian rejection of Ehud Barak’s peace plan; or of Bill Clinton’s peace plan; or of Ehud Olmert’s peace plan. Just the simplistic and ahistorical narrative of Palestinian blamelessness that underlies so much of the paper’s coverage.

From Point A, the view that Israel is entirely responsible for Palestinian suffering, it is only naturally to continue to Point B, the view that Palestinian actors, even the worst of them, are entirely not responsible for their contribution to the conflict. So in a report about an Islamic Jihad sniper attack from Gaza into Israel last May, Jerusalem bureau chief David Halbfinger described the Palestinian bullets as little more than an “expression of Palestinian impatience with Israel’s failure to alleviate dire humanitarian conditions in Gaza,” placing the ultimate blame for the shooting not with the terror group, which is depicted as lacking agency, but with Israel’s purported bad behavior.

The journalist was apparently pleased by this formulation, because the very next day he cast Hamas, too, as a group that “can express its impatience with weapons.”

And in November, after the paper had briefly acknowledged that Islamic Jihad is “listed as a terrorist organization by many countries,” the informative language was inexplicably scrubbed from the story. A follow-up report characterized Islamic Jihad as “nettlesome” and “unruly,” worthy descriptions of a stray tuft of hair, perhaps, but not for a group responsible for bombing Israeli malls, restaurants, and buses packed with civilians.

When you’ve developed the habit of describing antisemitic terrorists not as “antisemitic” nor “terrorists,” but rather as “impatient” and “nettlesome,” the muscle memory can easily take you to Point C, where you ignore and erase examples of antisemitism in the U.S., too. Because if you hesitate to note that Islamic Jihad, with its bomb vests and rocket squads, is antisemitic, why would you do so for Alice Walker, with her Pulitzer Prize? If you’ve learned to ignore Hamas’s claim that Jews control world governments, why would you second guess the antisemitic allegation when choosing a cartoon to feature in your newspaper?

To be sure, anti-Israelism isn’t the only cause of the newspaper’s foggy vision when it comes to antisemitism. Its handing of Jewish concerns is also influenced by domestic politics, identity politics, and the unique nature of antisemitism as a bigotry that purports to “speak truth to power,” a slogan embraced by many journalists. But as long as the newspaper’s narrative encourages reporters to ignore, downplay, or whitewash antisemitism by anti-Israel actors in the Middle East, we shouldn’t be surprised to find the same in coverage of antisemitic anti-Israel actors domestically.

None of this is to say the New York Times is institutionally antisemitic, or that the paper always ignores antisemitism. Undoubtedly, the newsroom is full of reporters who deplore anti-Jewish bigotry, and who will (and indeed do) periodically cover physical assaults on Jews in Brooklyn. But that reassurance only goes so far. The Times did not support, nor did it completely overlook, the Nazi persecution of Jews in the 1940s. And still, it now acknowledges its culpability in downplaying the slaughter of Jews in Europe.

The 2020s are not the 1940s. But in its contemporary journalism, the paper is culpable for helping a candidate who blamed American Jews for war in her quest for national office, and is responsible for spreading some of the beliefs that motivated the Poway shooter.

Americans, and especially Jews, deserve better. The newspaper’s editorial board put it well after the publication of the antisemitic cartoon: “the appearance of such an overtly bigoted cartoon in a mainstream publication is evidence of a profound danger — not only of anti-Semitism but of numbness to its creep, to the insidious way this ancient, enduring prejudice is once again working itself into public view and common conversation.”

Now it just needs to put that lesson into practice.