- 789

- 794SHARES

According to the profound reckoning of the erudite New York Review of Books, the southern Israeli city of Beersheba is Palestinian territory. By the editors’ logic, the same goes for the central Israeli cities of Ramle, Lod, Modiin (home of this Israeli researcher and over more than 90,000 other Israelis), as well as Ben-Gurion International Airport. The ruling by Review of Books editors from their lofty perch in Manhattan also places Nahariya, Acco, Nazareth in Palestinian territory.

The intellectual giants at the elite literary journal have made clear that, for them, it is the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan – categorically rejected by Palestinian Arabs and surrounding Arab states at the time – which is the basis for now determining what is Palestinian territory.

Thus, while The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Voice of America, Deutsche Presse-Agentur have all commendably corrected erroneous assertions that the disputed West Bank, and in particular areas in which Israeli settlements are located, are Palestinian territory, The Review of Book outliers have preferred to redraw the map entirely. When challenged about the designation of disputed West Bank land as “Palestinian,” NYRB editors cited the United Nations Partition Plan – a proposal roundly rejected by the Palestinian Arab leadership over seven decades ago – insisting that the West Bank is Palestinian territory. The natural conclusion about other areas also designated as part of the Arab state under the plan that the Arabs never accepted – Beersheba, Ramla, Lod, Modiin, Bet Shemesh, Acco, Nahariya, the airport, and more – is that they, too, are Palestinian territory. (On the other hand, under the 1947 Partition Plan, Palestinians have no right to Jerusalem, as it was intended to be an international corpus separatum, under United Nations administration.)

The issue arose with the mischaracterization of West Bank land in Omri Boehm’s June 9 article, “After Liberal Zionism, the One Hope for a Democratic Israel,” when the associate professor of philosophy at the New School for Social Research referred to a “coalition pact that cleared the way for Israel to annex a large tranche of Palestinian territory in the West Bank.”

Israel captured the West Bank in 1967 from the Kingdom of Jordan, which had occupied the territory since its 1948-49 war with Israel. Prior to 1948, the West Bank, like Israel, was administered by the United Kingdom.

In the 1990s, when Israeli and Palestinian leaders signed the Oslo peace agreements, the sides agreed that the status of the West Bank would be decided in negotiations between the sides, and today its rightful and ultimate disposition remains under contention.

Rejecting this provenance, editors responded:

The land referred to in the West Bank was, before 1948, all covered by the British Mandate for Palestine. Under the 1947 UN Partition Plan, it was designated Palestinian territory; the UN never recognized Jordanian sovereignty over the territory because, to the contrary, it always recognized it Palestinian territory. For the same reason, it also deems Israel’s control of the territory since 1967 as an occupation. The Oslo Accords have no current legal force: Israel has violated them, and both sides have rescinded their assent to them; they are a dead letter. That notwithstanding, the accords’ agreement in principle by both parties to haggle over land for peace and a two-state solution did not alter the fact that the Palestinian party had authority to negotiate over such matters by virtue of UN recognition of the Palestinian right to sovereignty in the occupied territory of the West Bank (and Gaza). The mischaracterization here would be to call the West Bank “disputed” territory; this is to erase the fact of Israel’s occupation of the land since 1967 and to normalize its illegal settlement of tranches of that land.

It is completely disingenuous to invoke a plan which Palestinian Arabs and Arab states rejected at the time as “lack[ing] legal validity” to now argue that it set out the boundaries of Palestinian territory. In 1979 document, the United Nations described the Arab rejection of the plan:

The Arab States, as well as several others, declared that they would not consider themselves bound by the General Assembly recommendation since they considered that it was contrary to the United Nations Charter. Others voiced apprehension over the future implications of the vote to partition Palestine. An excerpt from a statement conveying the mood of the hour follows:

“A fateful decision has been taken. The die has been cast. In the words of the greatest American, ‘We have striven to do the right as God gives us to see the right’. We did succeed in persuading a sufficient number of our fellow representatives to see the right as we saw it, but they were not permitted to stand by the right as they saw it. Our hearts are sad but our conscience is easy. We would not have it the other way round. …”

“No man can today predict whether the proposal which these two great countries had sponsored and supported will prove beneficient or the contrary in its actual working.

“We much fear that the beneficence, if any, to which partition may lead will be small in comparison to the mischief which it might inaugurate. It totally lacks legal validity. We entertain no sense of grievance against those of our friends and fellow representatives who have been compelled, under heavy pressure, to change sides and to cast their votes in support of a proposal the justice and fairness of which do not commend themselves to them. Our feeling for them is one of sympathy that they should have been placed in a position of such embarrassment between their judgement and conscience, on the one side, and the pressure to which they and their Governments were being subjected on the other.” (Emphases added.)

Thus, the Arab states and Palestinian leadership did everything in their power to ensure that United Nations Resolution 181, ie the Partition Plan, was a dead letter – to borrow from the editors’ language – by voting against it, lobbying others to do so, and by launching a war of annihilation when diplomacy failed. Yet, three-quarters of a century later, the NYRB resurrected the stillborn plan.

On the other hand, the NYRB dismisses the Oslo Accords as a “dead letter” with “no current legal force,” despite the fact that unlike the Partition Plan, the Palestinian leadership, did approve these agreements. And it is not true that “both sides have rescinded their assent to them.” On the Israeli side, a Knesset decision is necessary to revoke its assent to the Oslo Accords, and that never happened. Similarly, the necessary Parliament decision on the Palestinian side did not take place.

Omar Shaban, founder and director of the Gaza-based PalThink for Strategic Studies, described the implications of the abrogation of the Oslo Accords:

Cancelling the Oslo Accords would effectively remove the legal justification for the PA. Quite simply, it would mean dismantling the PA, laying off its employees, ending international funding, and nullifying the economic agreements between the PA and Israel as well as between the PA and many other countries around the world. It would also mean an end to security coordination between Israel and the PA, which would facilitate the return of the Israeli military to parts of the West Bank designated as Area “A.” …

Ending the Oslo accords and dismantling the PA would also lead to an exodus of foreign diplomatic representatives from Ramallah, as well as a freeze on all joint economic projects between the Palestinian and Israeli private sectors in the fields of energy, cement, electricity, telecommunications, and others, resulting in economic losses of at least hundreds of millions of dollars.

But none of this happened. The Palestinian Authority is still standing, and Mahmoud Abbas is still president, in the 16th year of his four-year term, none of which would be possible without the continuing existence of the Oslo Accords.

On a second, separate point, the NYRB powers that be stand by Boehm the philosopher, once again inventing an absurd, baseless claim to support their case. In this instance, the editors maintain that Israel lays claim to the entire West Bank, including cities under full Palestinian control, such as Ramallah, Jenin, and Nablus.

In his article, Boehm had alleged:

Since the population in the areas now claimed by Israel’s government is about 50 percent Arab, we are not in fact witnessing a slide toward apartheid but rather the rapid rehabilitation of the idea of forced ‘population transfers,’ a laundered phrase for ethnic cleansing.

CAMERA wrote editors, inquiring how Boehm reached this figure, the basis for his vitriolic smear that Israel is sliding towards “ethnic cleansing.” Regarding the territory that Israel claims, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s annexation plan reportedly entails at most the Jordan Valley and Jewish settlements elsewhere (all in Area C, meaning under Israeli security and civilian control) in the West Bank. So, CAMERA’s assumption was that the geographical area in question (ie, “areas now claimed by Israel’s government”) includes those lands, together with pre-1967 lands, the Golan Heights and parts of Jerusalem beyond the Green Line.

But the editors’ response indicated their belief that Israel’s claim goes much beyond the stated outline of the annexation plan, as “the author is referring to the entire population of the West Bank.” The editors, probably not even understanding they are saying, blunder on:

The proportion you cite of about 75:25 (Jewish/Arab) is derived by Israeli official statistics’ counting the Israeli settler population of the West Bank (including annexed areas of East Jerusalem) as inhabitants of Israel, but excluding Arab inhabitants of the West Bank as not citizens; such statistics are gerrymandered, not reliable, and have no factual basis in reality.

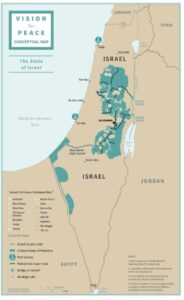

The justification for treating this combined territory of Israel and the West Bank as unitary, in terms of population-counting, comes not only from the Israeli government’s avowed commitment to retain control over it all, a claimed dominion endorsed by the Trump Deal of the Century, which leaves sovereignty over the whole territory at Israeli disposal, but also from official Israeli maps used on government websites and in school textbooks such as this from the Ministry of Education that show the whole territory of the West Bank as integral to Israel—with no allusion to the Green Line or the 1967 border and with Palestinian towns and place names erased.

Of course, these contortionist arguments are self-contradictory. On the other hand, editors bemoan the fact that not all Palestinians are included in Israeli statistics, as they are not citizens. On the other hand, they complain that Israel treats Israel and the West Bank as unitary. They can’t have it both ways.

Indeed, Israel does not count Palestinian Arabs living under complete Palestinian rule in locations like Ramallah, Nablus, Hebron, Jenin and so in its official statistics. That’s not gerrymandering; it’s reflecting the reality that Israel has zero claims on those Palestinians and the land where the live. It’s not “justification for treating this combined territory of Israel and the West Bank as unitary,” it’s the opposite; it’s drawing distinctions between different parts of the West Bank, those limited areas in which Israel does have a claim versus the much larger area where most of the Palestinian population resides and where Israel has no claim. Indeed, the Trump “Peace to Prosperity” does not endorse an imagined “Israeli government’s avowed commitment to retain control over it all”; it proposes Israeli control over thirty percent of the West Bank.

Finally, The NYRB relies on a Ministry of Education app to assert that Israel has a claim over the entire West Bank. If that’s the case, then why is Ramallah not part of Netanyahu’s sovereignty plan? Editors don’t — or can’t — explain why an Education Ministry app reflects Israeli policy better than Israeli policy reflects Israeli policy.

The intellectual rigorousness displayed here is as underwhelming as citing a long-moribund plan wholly rejected by the Palestinians as the basis for determining the contours of Palestinian territory. New School in New York, where Boehm is an associate professor of philosophy, boasts a “tradition of groundbreaking inquiry” and a “distinctive intellectual tradition.” Groundbreaking perhaps. But if article and the editors’ response (which is likely a parroting of what Boehm fed them) is what is meant by groundbreaking, intellectual tradition is better served without it.