Not sober reporting: An outburst by Mohammed El-Kurd, a resident of Sheikh Jarrah and The Nation’s “Palestine” correspondent

Eviction of Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah who failed to prove ownership or show payment of rent as protected tenants are at the center of massive international attention. As Palestinian leaders inflame with baseless charges of “ethnic cleansing” and “war crimes” and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestinian terror organization calls for “all forms of resistance against Israel,” reporters have a sober responsibility to adhere to high standards journalism professionalism, ensuring objective reporting, fact-checking and careful attribution of unverified claims.

Unfortunately, however, the journalistic performance is as spotty as the residents’ ownership bids.

Thus, in its coverage yesterday, the Associated Press adopted as fact unsubstantiated claims by Palestinian activists and other critics that Arab residents of eastern Jerusalem face discrimination when it comes to the granting of building permits. AP’s Ilan Ben Zion alleged (“Israel police evict Jerusalem residents from disputed houses“) that “thousands [of Palestinian residents of east Jerusalem] face the threat of demolition because of discriminatory policies that make it extremely difficult for Palestinians to build new homes or expand existing ones.”

The AP’s hyperlink leads a 2019 article, “New data shows settlement surge in East Jerusalem,” which also fails to document a discriminatory policy of granting building permits. That article had argued:

The data also showed strong evidence of decades of systematic discrimination, illustrated by a huge gap in the number of construction permits granted to Jewish and Palestinian residents. …

The data was acquired and analyzed by the Israeli settlement watchdog Peace Now, which says it only obtained the figures after a two-year battle with the municipality. It says the numbers show that while Palestinians make up more than 60% of the population in east Jerusalem, they have received only 30% of the building permits issued since 1991. …

Peace Now found that in the first two years of Trump’s presidency, authorities approved 1,861 housing units in east Jerusalem settlements, a 60% increase from the 1,162 approved in the previous two years. The figures show that 1,081 permits for settler housing were issued in 2017 alone, the highest annual number since 2000. A total of 1,233 housing units were approved for Palestinians in 2017 and 2018, according to Peace Now.

The data did not include the number of Jewish and Palestinian applications, or the rates of approval, though many Palestinians acknowledge not applying because they say it is nearly impossible to get a permit.

AP belatedly added the latter sentence after CAMERA’s Gilead Ini objected that without the figures for permit requests from each population, numbers for granted permits by themselves cannot shed light on the question of discrimination. Following the addition of the last sentence excerpted above, Ini panned AP for its stubborn clinging to the discrimination charge, despite the lack of evidence:

Incredibly, even after AP added the language clarifying that their data doesn’t account for the number of requests by each demographic group, the wire service refused to remove the unsubstantiated allegations about Israeli discrimination. It retained the pseudo-scientific claim that discrimination is “illustrated by” the gap in the number of construction permits granted.

As CAMERA has reported in the past, the difference in permit requests across Jerusalem has indeed correlated with the difference in permits issued by the city, a fact inexplicably elided in too many media reports.

AP’s persistence in again reporting the disputed and unsubstantiated claim as fact in yesterday’s story was particularly glaring given the wire agency’s initial skepticism when it came to published information from the Jerusalem municipality. Thus, initially, AP referred to “the city removing the family to make way for what it says will be a large special-needs school for Palestinian children in the area.” (Emphasis added.)

AP’s persistence in again reporting the disputed and unsubstantiated claim as fact in yesterday’s story was particularly glaring given the wire agency’s initial skepticism when it came to published information from the Jerusalem municipality. Thus, initially, AP referred to “the city removing the family to make way for what it says will be a large special-needs school for Palestinian children in the area.” (Emphasis added.)

Following communication from CAMERA questioning why the municipality’s information about plans to build the school warranted an “it says” qualification while claims from activists and residents about discriminatory policies are accepted as fact, AP amended that passage.

For its part, Reuters neglected to report that the Salhiya family, which was evicted yesterday, failed to prove its claim of ownership in court (“Israeli police evict Palestinians, tear down east Jerusalem home“). Thus, Reuters’ Stephen Farrell reported:

Police and the Jerusalem municipality said the family had been given “countless opportunities” to hand over the land since an evacuation order was served in 2017.

It said authorities were enforcing a court-approved eviction order of “illegal buildings built on grounds designated for a school”.

But at no point does he note that the family could not prove ownership. To its credit, AP had reported:

Hagit Ofran, a researcher for the anti-settlement group Peace Now, acknowledged the family had been unable to prove ownership. But she said it was clear they have lived there for years.

Reuters’ selective account also neglected to mention that the land was expropriated (from its owners, not the Salhiyas) in order to build a special needs school for the benefit of Arabs from across eastern Jerusalem. Nor did Reuters mention that the city provided the evicted family with a rented home at the municipality’s expense, as AP reported.

A third wire service, Agence France Presse, repeated Palestinian claims that they purchased their Sheikh Jarrah properties from Jordan following the 1948 war, even as Jordanian documents show that the families never did gain ownership. Thus, in its Jan. 18 article, AFP reported: “Palestinians say their homes were legally purchased from Jordanian authorities who controlled east Jerusalem between 1948 and 1967.”

But as CAMERA’s Alex Safian previously reported:

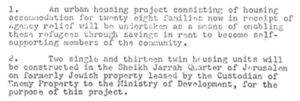

In 1956 the Jordanian Government reached an agreement with UNRWA to use the vacant Ashkenazi land in Sheikh Jarrah to build houses for 28 Palestinian refugee families. Under the scheme the Custodian leased the land to the Jordanian Ministry of Development, and the United Nations (UNRWA) funded the construction:

The refugees would agree to give up their refugee assistance and ration cards and would pay nominal rent for a probationary period of three years and three months. Those tenants who lived up to the lease terms would be allowed to sign a long-term lease of 30 years, and after that a further 33 years.

The tenants claim that under a side agreement they received title to their homes after the initial three-year period, but there is no evidence of such an arrangement, which would obviously conflict with the fact that they had to sign a lease.

In any event, there is no evidence that any of the 28 families ever gained title to the homes from Jordan or UNRWA. They were tenants paying rent.

In addition, AFP reprised the canard about a double standard in Jews versus Arabs reclaiming property lost in 1948, stating:

In some cases, Jewish Israelis have lodged legal claims to plots they say were illegally taken during the war that accompanied Israel’s creation in 1948.

Israeli law allows Jewish Israelis to file such claims, but no equivalent law exists for Palestinians who lost land during the conflict.

In fact, as Safian has explained:

Property left behind by Arabs who fled during the fighting in 1948 (ie, absentee property) was turned over to Israel’s Custodian of Absentee Property, which transferred title to state or related bodies for public purposes, such as housing the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Arab countries who found refuge in Israel. The Custodian held the value of the property in trust for the registered Arab owner (with adjustments for inflation and interest). These actions were completely within international norms, and the office itself and its functions were inherited from the similar British Mandate office.

Those registered Arab owners who are citizens or residents of Israel (including Palestinians resident in East Jerusalem) are eligible to file for compensation from the Custodian, but they were pressured not to make claims, lest that legitimize Israel’s existence and sovereignty. Still, over the years at least 14,692 claims have been filed, claims have been settled with respect to more than 200,000 dunums of land, more than 10,000,000 NIS (New Israeli Shekels) has been paid in compensation, and more than 54,000 dunums of replacement land in Israel has been given in compensation. Israel has followed this generous policy despite the fact that not a single penny of compensation has ever been paid to any of the more than 500,000 Jewish refugees from Arab countries, who were forced by the Arab governments after 1948 to abandon their homes, businesses and savings.

West Bank Palestinians are not eligible to file with Israel for property they lost after 1948, but neither are Israeli Jews eligible to file for property they lost in the West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem) after 1948. This has been the position of the Israeli government and was confirmed in the so-called Valero decision by Israel’s Supreme Court.

Israeli Jews are eligible to file for compensation (or return in rare cases) for land that was lost in East Jerusalem after 1948. Ownership of much of the land taken by the Jordanian Custodian of Enemy Property was transferred to the Jordanian government, which used it, for example, to construct government buildings in East Jerusalem, and to create the Dheisheh Refugee Camp – which is built entirely on Jewish-owned land. In addition, Palestinian refugee camps at Qalandia and Anata were built in part on Jewish land that had been taken by the Jordanian Custodian. (See Arab Building in Jerusalem: 1967—1997, Israel Kimhi, p48-49; for Dheisheh, see also, from the leaked Palestine papers, NSU Draft Memo Re: Rights of Jews Within the OPT Acquired pre-1967.)

None of the land used for refugee camps or government buildings in East Jerusalem can be returned to the original Jewish owners, but they can file for compensation. The land in Sheikh Jarrah was an exception because it was leased to the Jordanian government rather than taken by eminent domain, and was therefore still on the books of the Jordanian Custodian as Jewish land and could be returned to the successors of the original Jewish owners.

The aforementioned information has been available for more than half a year. Journalists who ignore it may not share Mohammed El-Kurd’s extension of the proverbial middle finger in face of “the genocidal death cult that is Israel.” But their omissions and failures to sift facts from baseless allegations certainly do reflect a flippant disregard for standards of ethical journalism.