- 291

- 301SHARES

For decades, we’ve been hearing from anti-Israel media, activists, and NGOs, and even online lodging service Airbnb, that the settlements are the main obstacle to peace – a statement that contains within it an implicit assumption that Israeli Jews will not be able to live in a majority Arab future state of Palestine. For, if they could simply become citizens of the state, then some of the land on which the settlements sit could be transferred to Palestine, and there would be no obstacle. Now, an opinion piece in the Forward, defending comments by Marc Lamont Hill, asserts that the opposite is true, that is, that Israeli Jews will be welcome in a majority Arab future state (albeit a bigger one than that envisioned by proponents of a two-state solution). And not only that, but also, those who don’t think so are making “deeply racist and Islamophobic assumptions about who the Palestinians are and what they want.” (“From The River To The Sea’ Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means,” by Maha Nassar, December 3, 2018.)

Professor Maha Nassar

If author Maha Nassar is correct in this, she should inform Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas – who has said that, “in a final resolution, we would not see the presence of a single Israeli – civilian or soldier – on our lands,” – that he is being deeply racist and Islamophobic. His government has banned the sale of land to Jews and recently sentenced two Palestinians to 15 years of hard labor for the crime of selling land to Jews. Nassar might also want to inform the UN Security Council that its Resolution 2334, which “express[ed] grave concern that continuing Israeli settlement activities are dangerously imperiling the viability of the two-State solution based on the 1967 lines,” that that resolution, too, was deeply racist and Islamophobic.

On the one hand anti-Israel media and activists want us to believe that Israeli Jews can’t live in Palestine, and therefore the settlements are an obstacle to Palestinian statehood, and on the other hand, we are now being told that Jews will be just fine in a (larger) Arab-majority state. These two propositions simply can’t simultaneously be true.

Of course, the “free Palestine” that Nassar describes, one that would go “from the River to the Sea,” would include not only what is now Israel and the West Bank, it would also include what is now Gaza. Gaza is where, in 2006, the residents elected to power a genocidal terrorist regime that promptly expelled its opposition in a violent coup. Article seven of the Hamas Charter reads, “the Prophet, Allah’s prayer and peace be upon him, says: “The hour of judgment shall not come until the Muslims fight the Jews and kill them, so that the Jews hide behind trees and stones, and each tree and stone will say: ‘Oh Muslim, oh servant of Allah, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him,’ except for the Gharqad tree, for it is the tree of the Jews.” Contrary to Nassar’s claim and much erroneous reporting, this Charter was not repealed by or overridden by the 2017 policy document. Hamas officials’ statements express the same sentiment. In 2017, Hamas official Mahmoud Al-Zahhar said that “removing the Jews from the land they occupied in 1948 is an immutable principle, because it appears in the Book of Allah.” More recently, one of that group’s leaders, Yahya Sinwar, called to “eat the livers” of Israelis.

Surely, such statements don’t bode well for the prospect of coexistence.

Marc Lamont Hill at the UN

While Nassar seems to admit that Hamas’s use of the phrase “from the river to the sea” is indeed genocidal, she claims that not everyone who says it means it that way. (“Citing only Hamas leaders’ use of the phrase, while disregarding the liberationist context in which other Palestinians understand it, shows a disturbing level of ignorance about Palestinians’ views at best, and a deliberate attempt to smear their legitimate aspirations at worst,” she writes.)

It’s undoubtedly true that within the Palestinian population, there are individuals who seek peaceful coexistence. But even under the most generous interpretation of the phrase, the one that Professor Nassar and Marc Lamont Hill want us to believe that they mean, such an outcome would result in a loss of Jewish self-determination – a right that Arabs presently have in 21 countries and that Muslims have in 56 countries. It would also result in the loss of the only Jewish homeland, as well as the loss of a refuge for persecuted Jews in the diaspora. It would be the loss of the only place on earth where Jews can go and find their holidays marked by school and government closures, their calendar in use, their language spoken as the primary language.

Professor Nassar, moreover, seems blissfully ignorant of 1300 years of history, in which Jews and Christians living in Arab lands were subjected to second-class or “dhimmi” status; a kind of Middle Eastern Jim Crow. As dhimmis, Jews, among other restrictions, “were excluded from public office and armed service … were forbidden to bear arms. … not allowed to ride horses or camels, to build synagogues or churches taller than mosques, to construct houses higher than those of Muslims or to drink wine in public. … not allowed to pray or mourn in loud voices-as that might offend the Muslims. The dhimmi had to show public deference toward Muslims-always yielding them the center of the road.” Jews living as dhimmis in Arab lands were periodically subjected to violence with no recourse. Finally, in the 1940s and 50s, Jews living in Arab lands were expelled. The idea that turning Israel, the world’s only Jewish majority state, into the world’s 22nd Arab state would likely result in hardship for Israel’s Jews is not, as Professor Nassar asserts, based on “deeply racist and Islamophobic assumptions;” it’s based on a realistic reading of history.

In addition, the piece, by a self-described “scholar of Palestinian history,” is rife with historical distortions. The op-ed veers into surreal territory with the following passage:

Moreover, the proposed borders of the two states meant that the Jewish state would have roughly 500,000 Palestinians living in it as a minority. And while the Israeli narrative holds that those Palestinians would have been welcomed as equals in the new Jewish state, the clashes between Jews and Arabs in Palestine that followed the UN vote, particularly the attacks by Zionist militants and the subsequent forcible removal of Palestinians from their homes and lands in areas allotted to the Jewish state, led Palestinians to conclude otherwise.

What Nassar refers to as “clashes” and “attacks by Zionist militants” was actually an invasion of Israel by five Arab armies, assisted by the Palestinian Arabs, and the fledgling Jewish state’s defense against that invasion. The claim that Arabs would be a welcome minority in Israel is not a “narrative.” In fact, today, two million Arabs live in Israel as citizens, and Israel’s Basic Law guarantees them equal rights. Tellingly, four of the five links in that paragraph are to Wikipedia pages; the fifth is a link to a book by discredited scholar Ilan Pappe.

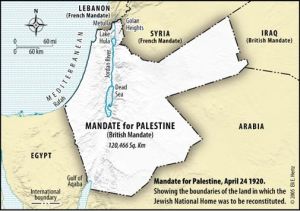

Those are not the only ahistorical points in the history professor’s op-ed. She writes that in 1947, Arabs living under the British Mandate “saw all of Palestine — from the river to the sea — as one indivisible homeland” and that the Arabs of Palestine opposed the UN Partition Plan because they “couldn’t stand to see their beloved country split in two.” Of course, Palestine was not a “country” in 1947, or ever. In 1947 it was a territory ruled by the British under the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, which Mandate was for the purpose of establishing a Jewish homeland. The Palestinian national movement began in 1964, and the pamphlet she relies on to support her contention appears to have been published in 1969. Moreover, the land had already been split in two when Transjordan was created. Notwithstanding Professor Nassar’s cultural appropriation of the Jewish story of Solomon and the baby, no one seemed to mind when Transjordan was cut off from the rest of Palestine.

Those are not the only ahistorical points in the history professor’s op-ed. She writes that in 1947, Arabs living under the British Mandate “saw all of Palestine — from the river to the sea — as one indivisible homeland” and that the Arabs of Palestine opposed the UN Partition Plan because they “couldn’t stand to see their beloved country split in two.” Of course, Palestine was not a “country” in 1947, or ever. In 1947 it was a territory ruled by the British under the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, which Mandate was for the purpose of establishing a Jewish homeland. The Palestinian national movement began in 1964, and the pamphlet she relies on to support her contention appears to have been published in 1969. Moreover, the land had already been split in two when Transjordan was created. Notwithstanding Professor Nassar’s cultural appropriation of the Jewish story of Solomon and the baby, no one seemed to mind when Transjordan was cut off from the rest of Palestine.

Nassar writes that in the 1960s, “the call for a free Palestine ‘from the river to the sea’ gained traction [as] part of a larger call to see a secular democratic state established in all of historic Palestine.” Yet, at the time, there was not a single secular democratic Arab state (nor is there today). Where was the call for a free Egypt from the Sinai to the Libyan border? Or the call for a free Jordan, from the river to Iraq? It’s hard to take seriously the claim that “Free Palestine from the river to the sea” was ever about democracy, and not about Jews.

Also absurd is her claim that there was “an Israeli media campaign following the 1967 war that claimed Palestinians wished to ‘throw Jews into the sea.’” The source that she cites for this does not support her implication that such statements were never actually made. On August 2, 1948, the New York Times, hardly a Zionist mouthpiece, reported that “Sheikh Hassan el-Bana, head of the Moslem Brotherhood, largest of the extremist Arab nationalist organizations, declared in an interview today: ‘If the Jewish state becomes a fact, and this is realized by the Arab peoples, they will drive the Jews who live in their midst into the sea.’” In 1967, Egypt blockaded Israel’s port, expelled UN troops, and broadcast its intentions to attack Israel by radio. Jordan attacked, despite Israel’s request to Jordan to keep the ceasefire. Other verbal threats emanating from Egypt, Jordan, Iraq and Syria prior to the 1967 war have been well documented. On June 1, 1967, Ahmed Shukairy, then-Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, said, “this is a fight for the homeland – it is either us or the Israelis. There is no middle road. The Jews of Palestine will have to leave. We will facilitate their departure to their former homes. Any of the old Palestine Jewish population who survive may stay, but it is my impression that none of them will survive.”

While she cites a 2017 poll claiming that “only a small minority of Palestinians see “expulsion” as a solution to the conflict – 15% — which is incidentally the same percentage of Israelis who view this as the only solution,” she omits that Israeli Arabs were included with “Palestinians” in this poll, skewing the results, and that only 11 percent favored Nassar’s preferred outcome of “one state solution with equal rights for Jews and Palestinians.” The poll also uses a strange methodology in which participants were permitted to choose multiple acceptable answers, but the poll only counted one answer per person. A more recent poll shows that 35 percent of West Bank and Gaza residents support “armed resistance” – not a process that is likely to result in peaceful coexistence.

As for Nassar’s claim that Palestinians “want to be able to choose the leaders who control their lives,” they should perhaps take that up with Mahmoud Abbas, who is about to start the 15th year of his elected four-year term of office, or with Hamas, which throws its political opposition off of rooftops. Until Palestinians are willing to hold their own leaders to account, democracy will remain out of reach for them.